At 8:15 AM on August 6, 1945, a deadly force exploded into the global consciousness when the first weaponized atomic bomb—developed and detonated by the United States—decimated Hiroshima, Japan killing 150,000 people, around 90% of the city’s inhabitants. Three days later, before its devastating impact was fully understood, the same force was wielded against Nagasaki, Japan resulting in around 75,000 deaths.1 The final death count is still uncertain due to multiple factors: those near ground zero were incinerated or lost to the sea, and deaths resulting from radiation and birth defects were never included. The invention and use of the nuclear bomb was credited with ending the Second World War, its horrors justified as a necessary sacrifice for peace.

The United States’ nuclear history is not limited to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The first victims of nuclear weapons were U.S. citizens and soldiers who suffered from radiation from nuclear testing in New Mexico, Utah, and Nevada in the 1940s. This includes Indigenous populations and other minorities who mined Uranium ore for the United States government, who also suffered from exposure to radiation and were denied protections and proper care. 2

Today, nine countries are known to possess nuclear weapons and over 30 use nuclear energy.

On the 75th anniversary of the nuclear attacks, Elongated Shadows revisits their effects and aftermath in an effort to encourage a more measured response to current nuclear tensions. Gathering artists forever connected by tragedy, Elongated Shadows prompts reflection on themes of forgiveness, identity, and heritage.

Kei Ito is a third generation hibakusha, an atomic bomb survivor, whose nuclear heritage originates in his grandfather’s experience and survival of the Hiroshima bombing. Ito’s grandfather, Takeshi Ito, was a well-known anti-nuclear activist who died decades after the war due to complications from cancer caused by radiation.

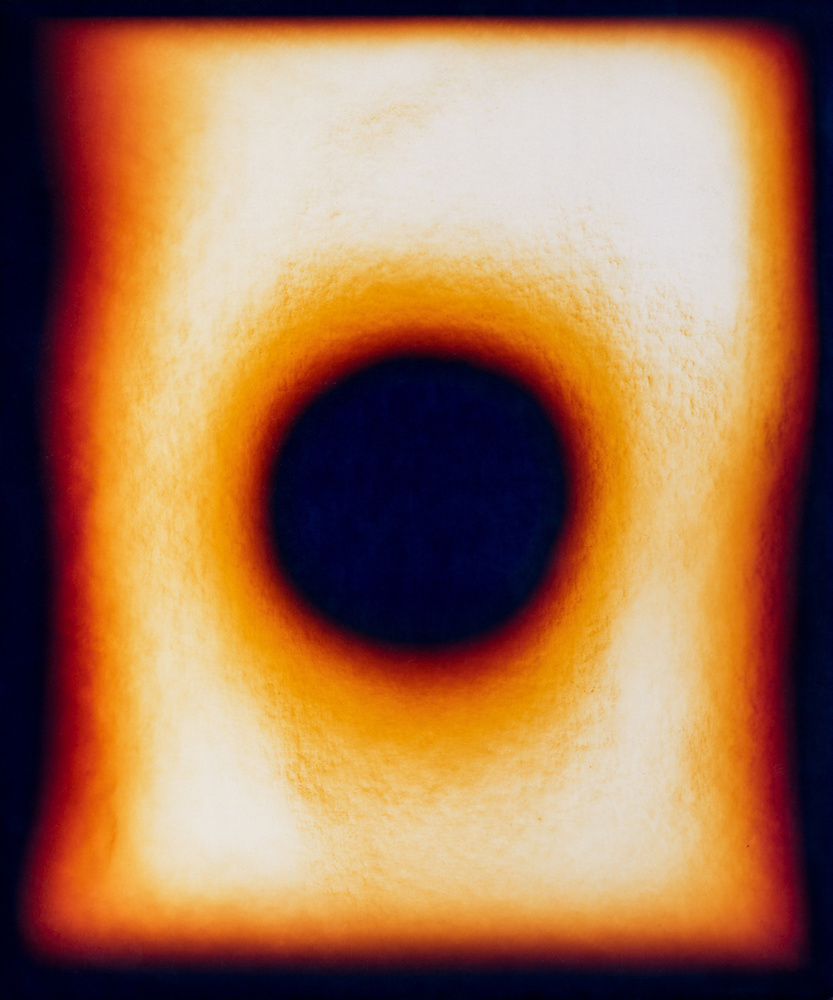

Although the younger Ito was only a child when his grandfather passed, he remembers Takeshi Ito recalling that day in Hiroshima was like “hundreds of sun[s] lighting up the sky.” Ito’s piece, Sungazing, reflects upon this phrase with 108 chromogenic prints, each one the result of exposing light-sensitive paper to sunlight for the duration of one breath. This shadow of Ito’s breath acts as a registration of his own life, one owed to his grandfather’s survival.

The repetition found in Ito’s sequential works hints at the vast numbers of people affected by nuclear weapons. The number 108 also has ritualistic importance in Japanese Buddhism and culture. From New Year’s Eve and into New Year’s Day, human-sized bells on temples across the country are struck 108 times to purge humanity of the 108 evil passions and desires, and to purify one’s soul for the upcoming year. In Sungazing, Ito contemplates ideas of redemption and forgiveness as he settles into a new home, America, reconciling with his familial past.

This number is also brought into the meditative and collaborative work between Ito and American sound artist, Andrew Paul Keiper, whose own grandfather was an engineer for the Manhattan Project—the experimental research initiative that created the first atomic weapons. Afterimage Requiem is a large-scale visual and sound installation containing 108 human-scale photograms and an hour-long 4-channel sound work.

The outlines of Ito’s body reference the nuclear shadows left by Japanese civilians who were burnt into the ground by the extreme heat of the blast. These 108 photograms—much like the shadows left across Hiroshima and Nagasaki—are direct negative exposures, true photographs. Ito’s emphasis on his own body is suggestive of recent evidence indicating that radiation alters and damages DNA, resulting in mutations that can be passed down genetically.

Keiper’s brooding sound piece plays above Ito’s prints, a spatial configuration that evokes the bombing itself: the Americans above and the Japanese victims below. Keiper arranges audio sampled from field recordings he conducted at American nuclear heritage sites, drawing upon his research into the production of the bomb. The composition conjures the facilities and methods that gave birth to the bomb, alongside the remote natural settings where the facilities were hidden. The sound prompts listeners to contemplate secret laboratories lost to time, to problematize the idea of the natural, and to ask difficult questions about things done in our name and in our defense.

Another work by Keiper, Bunker Music, is a suite of songs envisioning confinement within a fallout shelter during and after a nuclear war, and the inevitable fear, helplessness, mourning and dreaming experienced within. Its songs incorporate drones, looping, noise, field recordings and sound design to imagine the emotional terrain of the bunker.

Another artist with connections to the American side of the conflict is Suzanne Hodes. Hodes was the wife of Henry Linschitz, one of the main scientists behind the design and assembly of the atomic bomb. Distraught by the vast destruction of the bombs, both Hodes and Linschitz became ardent anti-nuclear activists after the war, founding groups such as Artists For Survival and United Campuses Against Nuclear War. Hodes’ activism is illustrated in her artwork as well.

Hodes’s painting Hiroshima Mother depicts a mountain of flesh and bone, recalling the visceral images of melting and mangled corpses that emerged from Japan after the war. She depicts a woman and infant in agony—caught between radioactive decomposition and the last breaths of life, atop a heap of bodies. The child presented here acts not just as a symbol of the mother’s personal loss, but the losses of a whole generation.

Hodes’ other work references the arms race of the Cold War. In her lithograph, Three Minutes to Midnight, Hodes replaces the biblical Apple of Knowledge with the Doomsday Clock, the visual countdown to a manmade global catastrophe. In the painting, there are only three minutes left to midnight, the moment when the world as we know it ends. The work, made in 1984, reflects the deepening nuclear tensions between the US and Soviet Union, which had many in fear that the end of the world was near.

Today, the Doomsday Clock is at 100 seconds to midnight.

Another expression of activism can be seen in photographer Ari Beser’s project for the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), an organization that won a Nobel Peace Prize in 2017. Beser’s grandfather, Lt. Jacob Beser, was a radar specialist, the only American on both the Enola Gay and Bockscar flights that dropped the atomic bombs. His main duty was to detonate the bombs in midair to maximize the damage.

While most of the artists in Elongated Shadows look to the past in order to contemplate on the present, Beser’s portraits capture and collapse the past and present into a single image. Beser’s photographs are of hibakushas standing in the locations where they witnessed the bomb’s explosion 70 years prior. Beser’s intimate portraits offer compelling images of humanity. They provide not only a glimpse into the Japanese experience of the war, but also reflect how Americans experienced the bombing: through cinema and still images.

Japanese artist Migiwa Orimo further examines the iconography and narrative of nuclear bombings. Fūin (sealed) consists of deconstructed toy B-29 planes—the plane type that dropped both bombs—and miniature nuclear bombs wrapped in linen and numbered with silk embroidery floss. In this realm of disjunction,the work exposes a relationship between public memory and private space, revealing how memories are shared and internalized; how they are stored and become stories; and, how memories and history collide. Here, we see no context, no landscapes, no people and no victims. Instead, we see these tools and weapons carefully wrapped, archived, and preserved in a museum-like display that also resembles a toy model kit, ready for assembly. Fūin (sealed) challenges our collective memories of the past and raises the question of who the authors may have been.

While Orimo’s work is a reflection of how collective history is preserved, Kyoto-born artist and Butoh dancer Azumi O E presents a new work, Q + A. This two-channel video conveys a dream-like fluidity of the past, present and future and takes a deep dive into the instantaneous span in which Hiroshima permanently altered human history. In Q + A, O E makes a dichotomous probe into an individualistic perspective of a world calamity as she investigates and interprets both momentum and memory through Butoh—a distinctly Japanese artform.

Overuse of the iconic mushroom cloud in visual media and film has reinforced an assumed distance from atomic catastrophe. Casual discussion of nuclear weapons and their potential uses trivializes an extremely deadly force; today, phrases such as “just nuke ‘em” can be heard on talk shows or read in public opinion polls, and in 2019, the U.S. withdrew from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty. Despite the lasting trauma spawned by the first nuclear tests and attacks, many Americans still do not comprehend the consequences and legacy of nuclear war. Elongated Shadows calls attention to this long-polarizing issue from the past in order to encourage better-informed decisions in the future.

Liz Faust

apexart NYC Open Call Exhibition

© apexart 2020

1. Dr. James N. Yamazaki, M.D., “Hiroshima and Nagasaki Death Toll,” Children of the Atomic Bomb, last modified October 10, 2007, Link.

2. Doug Brugge and Rob Goble, “The History of Uranium Mining and the Navajo People,” American Journal of Public Health 92, no. 9 (September 2002): 1410–19.

3. “Genetic Effects of Radiation in the Offspring of Atomic-Bomb Survivors,” Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF), accessed July 10, 2020. Link.

4. “Human Shadow Etched in Stone,” Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, accessed July 2, 2020, Link.

5. Guardian Staff, “Trump Suggests ‘nuking Hurricanes’ to Stop Them Hitting America – Report,” The Guardian, August 26, 2019, Link.

6. “The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty at a Glance,” Arms Control Association, August 2019, Link.