Historians, post-colonialists, even historians of science rarely recognize the importance of plants to the processes that form and reform

human societies and politics on a global scale. Plants seldom figure in the grand narratives of war, peace, or even everyday life in

proportion to their importance to humans. Yet they are significant natural and cultural artifacts, often at the center of high intrigue.

- Londa Schiebinger, Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World, 2004

Botany under Influence delves into the politics of plants and explores systems of meaning that have been impressed upon nature, flora, and seeds throughout eras of imperialism, colonialism, and globalization. Unearthing forgotten and parallel histories, this exhibition reveals how the exportation of natural resources has affected worldwide power structures and cultural behavior. It pushes us to reconsider common perceptions and representations about nature 'having always been there,' being 'neutral' or 'passive,' when instead plants embody the larger History and are integral actors in it.

This show investigates historical gaps and the economic and diplomatic implications of nature's uses and international exchange flow patterns. Its starting point is the imperial era, as early as the 15th century, when Western powers built their wealth by looting human and natural resources - systematically appropriating or exporting workforce, plants, and minerals. Throughout the ages and societies, control over flora and seeds has become a symbol of national, political, and food sovereignties.

Several research-based artworks highlight the human construct of botany and its links with geopolitics while reminding us that ultimately what is at stake is our collective memory and the way we envision and build our social structures in relation to our apexart nyc environment.

Exploiting & Erasing Local Knowledge

Often when thinking about botany, vintage natural history illustrations, where plants are inoffensive and decorative elements, come to mind. If, as a romantic idea, nature seems to be freed from interests, it might well be that it has always been manipulated - for good or bad.

With Herbarium of Artificial Plants (2001-present), Alberto Baraya (Colombia) has committed himself to collecting and classifying synthetic specimens (plastic, cloth, paper) found while following ancient routes of colonial, scientific, or naturalist expeditions of the 17- 19th centuries. Ironically, he has also reversed this process and travelled from the colonies to European centers. Presented as photographs and artefacts, his fictitious flowers create a utopian flora and attest to how botanical prints conveyed imperial representations. In this parodic re-enactment - from the Americas (California, Colombia) to Asia (Shanghai), Oceania (Australia, New Zealand), and Europe (Spain) - Baraya investigates the economic and political agendas behind the abusive inventorying and categorization of the colonies' indigenous flora. He denounces how the botanical plundering of those missions enabled the projection of imperial enterprises. They opened the way to territorial domination and requisition, and even to the classification of people, under the guise of scientific research. Not to forget that colonial powers changed the plants' names and imposed a Latin taxonomy, which dismissed indigenous knowledge and terminology. The act of renaming turned language into a tool of oppression, and further anchored the colonizers' domination while subordinating the local and native population.

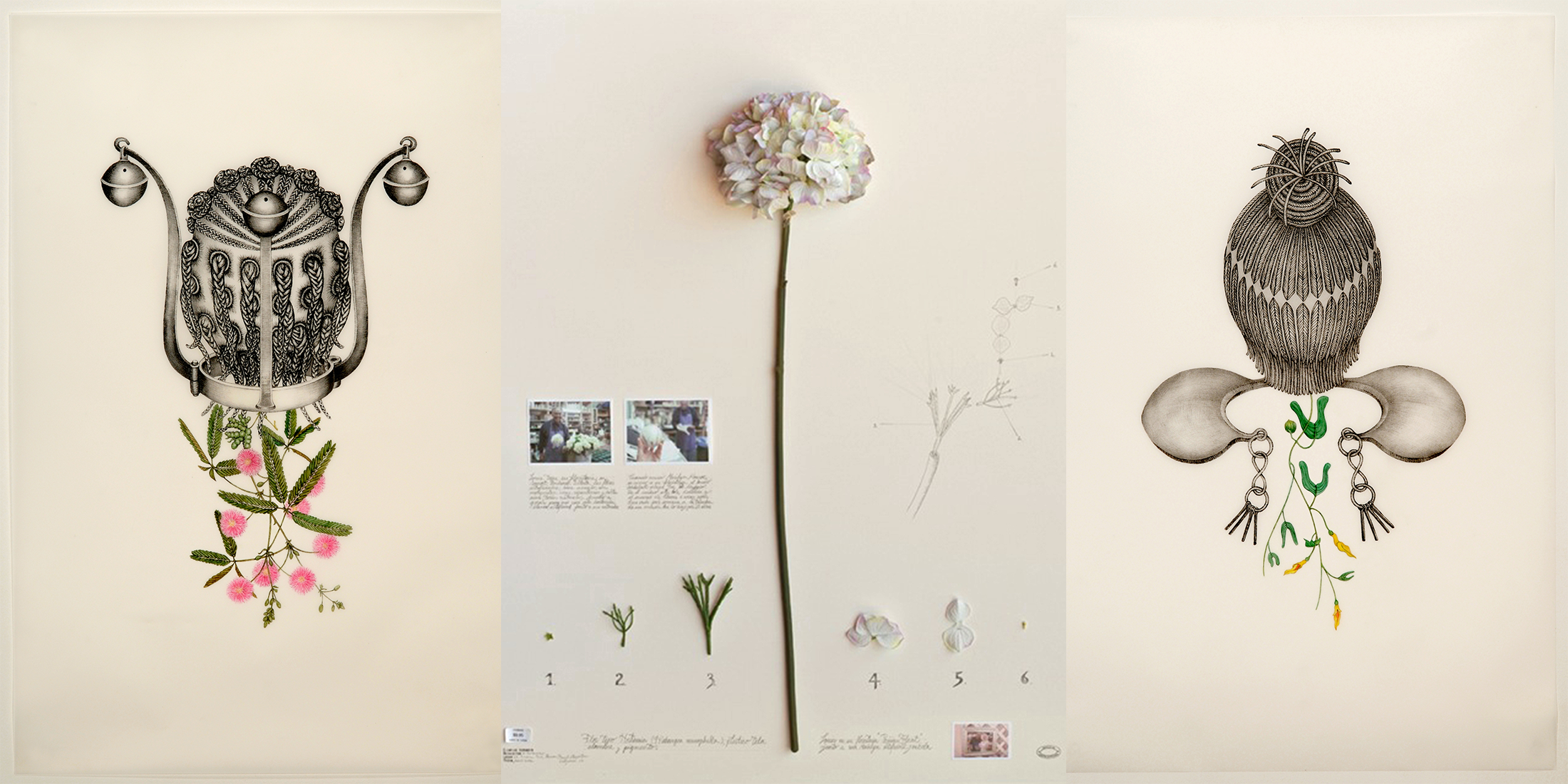

Joscelyn Gardner (Barbados) plays on natural history illustration aesthetics in her Creole Portraits III (2009-2011) lithographs. Her practice is grounded in Caribbean colonial archives (diaries, abolitionist publications, plantation records) and looks into the shared experiences of black and white creole women during the 18th and early 19th century. Gardner addresses gaps in the history of slavery - such as the masters' sexual abuse of women, either of their own wife or their slaves. Despite abortion being prohibited (masters would not pass up an opportunity to get free laborers), slaves secretly used natural abortifacients (thanks to their familiarity with healing herbs), a traditional knowledge now lost to time. If the 'miscarriage' was discovered, they were whipped and had to wear iron collars as punishment. Gardner intertwines depictions of the 'exotic' plants employed by those women with representations of the torture tools used and elaborate feminine African hairstyles. She pays homage to those anonymous slaves, 'naming' them in her prints' titles, and alludes to the extent of slavery's violent practices that were not limited to Barbados but existed in all the colonies, as far as the Indian Ocean.

Recording Loss & Questioning Independence

Another tribute, by Kapwani Kiwanga (Canada), is Flowers for Africa (2011-present), a process-oriented project that celebrates African countries' liberation struggles and access to political sovereignty after decades of negotiations and/or strife, from the late 1950s, with a peak in 1960, and finally in 1990 for Namibia. Reproducing floral decorations found in archival photographs of independence formalization, Kiwanga revives the solemn historical testimonies the bouquets 'silently witnessed' in the original ceremonies. With these recreated and reinterpreted arrangements, she comments on postcolonial transitions. The work could even point at the way colonial powers have dealt - or, more accurately, not dealt - with decolonization and its aftermath. Inspired by the official ceremonies embodying the passing of power, Kiwanga hints at the everlasting decorum and staging of diplomatic negotiations, from austerity and bureaucracy to extravagance and jubilation. As her fresh bouquet sculptures naturally wither during the show, she also asks us to consider what we choose to commemorate and why. The metaphor of flowers could be read as a way to push the viewer to see beyond appearances, pleasure, and beauty, because in several African countries (disguised or obvious) colonial ties were maintained despite autonomy officially being granted. This left a bitter taste for the independence process, and created enduring repercussions that still affect local politics, economy, and societies today.

Pia Rönicke (Denmark) examines the lasting impact of colonization in current events, as the empires' plundering of natural resources critically modified power relations. She poetically explores herbariums' archival and documentary potential to record disappearances and moderate loss. In the context of war-torn Syria, the 2012 transfer of food crops for safekeeping from Aleppo's gene bank - 135,000 species - to Svalbard Global Seed Vault, in Norway, inspired Rönicke's multimedia installation The Pages of Day and Night (2015). Navigating between temporalities, she mixes the results of cross-research: photogravures of plant samples collected during the 1760s Danish Arabia Expedition to Egypt and Syria, Syrian species recently sent to Norway, videos, press clippings, and poetry books by Adonis (Syria) and by Tomas Tranströmer (Sweden), respectively translated into English and Arabic. Interestingly, in October 2015, shortly after Rönicke created this installation, Syria asked the 'Doomsday Vault' to send 38,000 seeds back to Lebanon and Morocco to cope with drought and crop destruction in the region. Initially, this seed bank was primarily intended to receive specimens to preserve biodiversity in the event of a major natural disaster. Syria's seed withdrawal request has been the first example of a distinct role Svalbard could assume in the near future, in case of man-made catastrophes. This installation brings to the fore the ties between climate change / food security / migrations and political risks of destabilization or upheaval.

Shattered Landscapes & Spirituality

The video Remedies Australia (2015) by Sasha Huber and Petri Saarikko (Switzerland/Finland) investigates indigenous knowledge and more specifically healing techniques and traditional medicinal recipes linked to herbs. In this short film, the duo has interviewed Australian Aborigines and other inhabitants from the city of Mildura about their relationship with the eucalyptus tree. This plant is sacred to natives as they originally used it as a landmark to define their territories. The impact of colonization on the Aborigines has been disastrous and is slowly being officially acknowledged; this work reveals gaps in history, especially regarding imprints on the landscape and dispossession. By exporting eucalyptus throughout the world from Australia and introducing this species into several continents, imperial powers destroyed local Thousand-year-old scarred trees disappeared, erasing entire portions of territories. This poetic work is about sharing a culture and celebrating a collective heritage; it is about delving into beliefs and oral histories. Moreover, it includes a living and human testimony about post colonialism and a physical phenomenon that took place centuries ago but that still has tangible impacts. Past, present, and future dissolve. Unlike other works pointing to the links between botany, politics, and economy, this film highlights the important connections between botany and spirituality.

Beatriz Santiago Muñoz (Puerto Rico) presents reflections on the energetic power of vegetation while looking at the confused and contradictory ties between Puerto Rico and the United States, balancing between independence and sway. In the video Ojos para mis enemigos (2014), she wanders through the closed American naval base at Roosevelt Roads, Ceiba - one of several military infrastructures the U.S. imposed on Puerto Rico's territory, despite early caveats around the risks of reshaping the landscape and disturbing local biodiversity and waters. After ten years, the forest is gaining its importance and rights back, filtering and breaking the concrete. Native species mingle with alien species introduced by American military members who recreated their intimate environments with specimens such as betel-nut palms. Plants that were removed have resurfaced, such as cotton trees, which have a direct link to slavery. Within this dystopian landscape, a man picks cotton flowers for an orisha, a divinity in Santería. He will offer them to Obatalá, the creator of mankind. Santiago Muñoz's video acts as a summary - it touches upon past and present colonial structures and power relations, botany's exportation and importation throughout territories, and also on indigenous plant knowledge, beliefs, and spirituality.

Looking at history through the perspective of nature, the artists in Botany under Influence share counter official narratives around flora, drowning us in an abundance of 'strange flowers.' Despite the plants' beauty, our unease reminds us that beyond relations of power, nature's circulation routes take us back to our relationship with the land and have an impact on our origins, collective and individual memories, and survival.

human societies and politics on a global scale. Plants seldom figure in the grand narratives of war, peace, or even everyday life in

proportion to their importance to humans. Yet they are significant natural and cultural artifacts, often at the center of high intrigue.

- Londa Schiebinger, Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World, 2004

Botany under Influence delves into the politics of plants and explores systems of meaning that have been impressed upon nature, flora, and seeds throughout eras of imperialism, colonialism, and globalization. Unearthing forgotten and parallel histories, this exhibition reveals how the exportation of natural resources has affected worldwide power structures and cultural behavior. It pushes us to reconsider common perceptions and representations about nature 'having always been there,' being 'neutral' or 'passive,' when instead plants embody the larger History and are integral actors in it.

This show investigates historical gaps and the economic and diplomatic implications of nature's uses and international exchange flow patterns. Its starting point is the imperial era, as early as the 15th century, when Western powers built their wealth by looting human and natural resources - systematically appropriating or exporting workforce, plants, and minerals. Throughout the ages and societies, control over flora and seeds has become a symbol of national, political, and food sovereignties.

Several research-based artworks highlight the human construct of botany and its links with geopolitics while reminding us that ultimately what is at stake is our collective memory and the way we envision and build our social structures in relation to our apexart nyc environment.

Exploiting & Erasing Local Knowledge

Often when thinking about botany, vintage natural history illustrations, where plants are inoffensive and decorative elements, come to mind. If, as a romantic idea, nature seems to be freed from interests, it might well be that it has always been manipulated - for good or bad.

With Herbarium of Artificial Plants (2001-present), Alberto Baraya (Colombia) has committed himself to collecting and classifying synthetic specimens (plastic, cloth, paper) found while following ancient routes of colonial, scientific, or naturalist expeditions of the 17- 19th centuries. Ironically, he has also reversed this process and travelled from the colonies to European centers. Presented as photographs and artefacts, his fictitious flowers create a utopian flora and attest to how botanical prints conveyed imperial representations. In this parodic re-enactment - from the Americas (California, Colombia) to Asia (Shanghai), Oceania (Australia, New Zealand), and Europe (Spain) - Baraya investigates the economic and political agendas behind the abusive inventorying and categorization of the colonies' indigenous flora. He denounces how the botanical plundering of those missions enabled the projection of imperial enterprises. They opened the way to territorial domination and requisition, and even to the classification of people, under the guise of scientific research. Not to forget that colonial powers changed the plants' names and imposed a Latin taxonomy, which dismissed indigenous knowledge and terminology. The act of renaming turned language into a tool of oppression, and further anchored the colonizers' domination while subordinating the local and native population.

Joscelyn Gardner (Barbados) plays on natural history illustration aesthetics in her Creole Portraits III (2009-2011) lithographs. Her practice is grounded in Caribbean colonial archives (diaries, abolitionist publications, plantation records) and looks into the shared experiences of black and white creole women during the 18th and early 19th century. Gardner addresses gaps in the history of slavery - such as the masters' sexual abuse of women, either of their own wife or their slaves. Despite abortion being prohibited (masters would not pass up an opportunity to get free laborers), slaves secretly used natural abortifacients (thanks to their familiarity with healing herbs), a traditional knowledge now lost to time. If the 'miscarriage' was discovered, they were whipped and had to wear iron collars as punishment. Gardner intertwines depictions of the 'exotic' plants employed by those women with representations of the torture tools used and elaborate feminine African hairstyles. She pays homage to those anonymous slaves, 'naming' them in her prints' titles, and alludes to the extent of slavery's violent practices that were not limited to Barbados but existed in all the colonies, as far as the Indian Ocean.

Recording Loss & Questioning Independence

Another tribute, by Kapwani Kiwanga (Canada), is Flowers for Africa (2011-present), a process-oriented project that celebrates African countries' liberation struggles and access to political sovereignty after decades of negotiations and/or strife, from the late 1950s, with a peak in 1960, and finally in 1990 for Namibia. Reproducing floral decorations found in archival photographs of independence formalization, Kiwanga revives the solemn historical testimonies the bouquets 'silently witnessed' in the original ceremonies. With these recreated and reinterpreted arrangements, she comments on postcolonial transitions. The work could even point at the way colonial powers have dealt - or, more accurately, not dealt - with decolonization and its aftermath. Inspired by the official ceremonies embodying the passing of power, Kiwanga hints at the everlasting decorum and staging of diplomatic negotiations, from austerity and bureaucracy to extravagance and jubilation. As her fresh bouquet sculptures naturally wither during the show, she also asks us to consider what we choose to commemorate and why. The metaphor of flowers could be read as a way to push the viewer to see beyond appearances, pleasure, and beauty, because in several African countries (disguised or obvious) colonial ties were maintained despite autonomy officially being granted. This left a bitter taste for the independence process, and created enduring repercussions that still affect local politics, economy, and societies today.

Pia Rönicke (Denmark) examines the lasting impact of colonization in current events, as the empires' plundering of natural resources critically modified power relations. She poetically explores herbariums' archival and documentary potential to record disappearances and moderate loss. In the context of war-torn Syria, the 2012 transfer of food crops for safekeeping from Aleppo's gene bank - 135,000 species - to Svalbard Global Seed Vault, in Norway, inspired Rönicke's multimedia installation The Pages of Day and Night (2015). Navigating between temporalities, she mixes the results of cross-research: photogravures of plant samples collected during the 1760s Danish Arabia Expedition to Egypt and Syria, Syrian species recently sent to Norway, videos, press clippings, and poetry books by Adonis (Syria) and by Tomas Tranströmer (Sweden), respectively translated into English and Arabic. Interestingly, in October 2015, shortly after Rönicke created this installation, Syria asked the 'Doomsday Vault' to send 38,000 seeds back to Lebanon and Morocco to cope with drought and crop destruction in the region. Initially, this seed bank was primarily intended to receive specimens to preserve biodiversity in the event of a major natural disaster. Syria's seed withdrawal request has been the first example of a distinct role Svalbard could assume in the near future, in case of man-made catastrophes. This installation brings to the fore the ties between climate change / food security / migrations and political risks of destabilization or upheaval.

Shattered Landscapes & Spirituality

The video Remedies Australia (2015) by Sasha Huber and Petri Saarikko (Switzerland/Finland) investigates indigenous knowledge and more specifically healing techniques and traditional medicinal recipes linked to herbs. In this short film, the duo has interviewed Australian Aborigines and other inhabitants from the city of Mildura about their relationship with the eucalyptus tree. This plant is sacred to natives as they originally used it as a landmark to define their territories. The impact of colonization on the Aborigines has been disastrous and is slowly being officially acknowledged; this work reveals gaps in history, especially regarding imprints on the landscape and dispossession. By exporting eucalyptus throughout the world from Australia and introducing this species into several continents, imperial powers destroyed local Thousand-year-old scarred trees disappeared, erasing entire portions of territories. This poetic work is about sharing a culture and celebrating a collective heritage; it is about delving into beliefs and oral histories. Moreover, it includes a living and human testimony about post colonialism and a physical phenomenon that took place centuries ago but that still has tangible impacts. Past, present, and future dissolve. Unlike other works pointing to the links between botany, politics, and economy, this film highlights the important connections between botany and spirituality.

Beatriz Santiago Muñoz (Puerto Rico) presents reflections on the energetic power of vegetation while looking at the confused and contradictory ties between Puerto Rico and the United States, balancing between independence and sway. In the video Ojos para mis enemigos (2014), she wanders through the closed American naval base at Roosevelt Roads, Ceiba - one of several military infrastructures the U.S. imposed on Puerto Rico's territory, despite early caveats around the risks of reshaping the landscape and disturbing local biodiversity and waters. After ten years, the forest is gaining its importance and rights back, filtering and breaking the concrete. Native species mingle with alien species introduced by American military members who recreated their intimate environments with specimens such as betel-nut palms. Plants that were removed have resurfaced, such as cotton trees, which have a direct link to slavery. Within this dystopian landscape, a man picks cotton flowers for an orisha, a divinity in Santería. He will offer them to Obatalá, the creator of mankind. Santiago Muñoz's video acts as a summary - it touches upon past and present colonial structures and power relations, botany's exportation and importation throughout territories, and also on indigenous plant knowledge, beliefs, and spirituality.

Looking at history through the perspective of nature, the artists in Botany under Influence share counter official narratives around flora, drowning us in an abundance of 'strange flowers.' Despite the plants' beauty, our unease reminds us that beyond relations of power, nature's circulation routes take us back to our relationship with the land and have an impact on our origins, collective and individual memories, and survival.

Clelia Coussonnet is an independent cultural project manager, art journalist, and curator of contemporary art that has also curated an exhibition of previously unseen 19th century glass plate negatives from Uzbekistan at the UNESCO. She was then charged with launching a platform on visual arts from the Caribbean. Amongst other editorial projects, she regularly contributes to publications such as Another Africa, Diptyk, IAM, and Ibraaz.