Exploding the Container: A Spillage of Women

Contain yourself (women). If not plainly stated, this expectation is made explicit in the ways that women are judged and defined. Though this manifests differently across cultures and geography, a distinct type of derision is cast upon women who indiscreetly take-up space. Not only is the space occupied by her body contested, but also the vocalization of her opinions, assertions of intellect, demonstrations of ability, and expectations for recognition.

In 2014 I visited Hong Kong, and while wandering around on a Sunday, I was surprised to see multitudes of women on and around public spaces purposefully demarcated with tarp and cardboard. Although I recognized the rituals of weekend socializing, the epic proportions of exclusively female groups sharing foods, grooming, and worshipping in public is distant from my own experiences. The women, I later learned, are Migrant Domestic Workers (MDWs). Where I am from, women do not take-up space this way.

I am Chinese, but the context of my formative years, socialization, and education is Canadian. At home in Canada, I am part of continual conversations about what it would take to make space for women in the work place, social sphere, academic world, various fields of practice, and with one another, as allies countering a dominant culture. On occasion, a woman will recount an incident when she was given space but, more often, women relate meeting opposition in their struggle for space. For these reasons, witnessing the MDWs taking-up the space they need struck me as a noteworthy achievement.

My own preoccupation with female agency over space and the consequences of women's visibility led to considering the strategies being employed by MDWs and their effects. Through research undertaken by myself, co-curator Jennifer Davis, and artists Tings Chak, Stephanie Comilang, and Devora Neumark (in collaboration with Open Door and Rowena Yin-Fan Chan), How to Make Space approaches the matter of how the visibility of women is met.

Predominantly from the Philippines and Indonesia, over 300,000 women have migrated to Hong Kong for domestic or care-giving work. MDWs are required to reside with their employers, compounding the vulnerability of their positions created by restrictive government regulation of their movements and terms of employment. In the population-dense city, where surplus space is unlikely, guidelines governing conditions for domestic workers are loosely regarded and largely unmonitored by officials. It is not out of the ordinary for sleep accommodations to be in the living room, bathroom, kitchen, corridors, in their charge's bedrooms, on tables, appliances, balconies, and worse. Profoundly, MDWs perform vital roles while expected to be otherwise imperceptible, at once allowing their female employers to increase their own social presence and engage in pursuits outside the home. Under such strictures, it stands to reason that the women are literally 'uncontainable,' spilling out into the space of the city on Sunday, their only weekly 'holiday,' equipped with belongings typically considered personal and domestic. Their presence is asserted through activities that encompass streets, walkways, and parks with rituals of bodily care, creative expression, performance, religious worship, commerce, and gaming. Scents of food and sounds of shared cultures and languages occupy and energize the environment. These material, visual, aural, and olfactory aesthetics re-form the built environment of Hong Kong and hold a space of self-determination.

During duty hours, 'neutral' dress meets the expectations of paternal or suspicious employers. On Sundays, MDWs dress freely against anxieties and governance over women's sexuality. Autonomous self-fashioning, contrary to normative gender expectations, contributes prominently to the 'queering' of public space.

Within the deliberately designed communities of intermittent architecture, the agenda for the day appears to be leisure. Perhaps less obvious is the effective construction and maintenance of a network of information, resources, and action, both informally and formally organized. Regardless of whether these activities are considered legitimate, the women's occupation of time and space must be considered as their own.

Critics seeking to position the MDWs' presence as a nuisance point to the women's success in permeating public space. These arguments affirm classism, serving to privilege and legitimize other groups' use of civic space. The MDWs' hyper-visibility clashes with perverse expectations that they take-up the labour of care, but do not 'take-up' space in the city, and also highlights the insistence on cheap foreign labour while rejecting foreign bodies.

The women hold strong the practice of assembly against designations of difference and social hierarchy to the effect of complicating characterizations of femaleness. Their refusal to comply with prescriptive expectations on the female body risks being seen as unruly. The refusal to be invisible is radical.

Su-Ying Lee, co-curator

Female Feedback

I'm an architect: the discipline permeates my vocabulary and frames how my colleagues and I see and understand the city. When we design buildings, the people and activities become users and programs. Binaries such as public and private, commercial and domestic, and inside and outside articulate our understanding and approach to organizing spaces at all scales, from a single family home to a city-wide zoning map. Although our terminology can be a useful tool, in using it we risk erasing the specificity of individual experience and the ways identity can influence the built environment.

Unlike most of my architect colleagues, I am a woman. And in the last few years I have been struck by how my discipline, in its parlance and paradigms, negates gender.

I undertook How to Make Space as a journey in self-education. While most North American architects would travel around the world to experience the 'city without ground' of Hong Kong's soaring skyscrapers, I wanted to understand how women in this city enact a kind of architectural agency that I had never seen in my architectural training. Could their tactics of making space be used by other women? What might this mean for the field of architecture? Could their spatial knowledge, fed back in to the architectural discipline, reshape it?

The HSBC bank headquarters in Hong Kong's Central District has been a beacon for architects, financiers, and tourists since it was built in the 1980s. Its high-tech aesthetic, designed by English architect Sir Norman Foster, was intended to be a bold assertion of the economic sophistication and ambition of Hong Kong. The design was featured in television documentaries, heralded in an exhibition at MoMA in New York, and discussed in business journals including the Far Eastern Economic Review:

MDWs are integral to Hong Kong society, yet their spatial experiences are circumscribed by their intersecting gender, national, and class identities. The women's interventions in the existing architecture afford them spaces of human comfort neither found in their spaces of work nor provided by Hong Kong's official city planning.

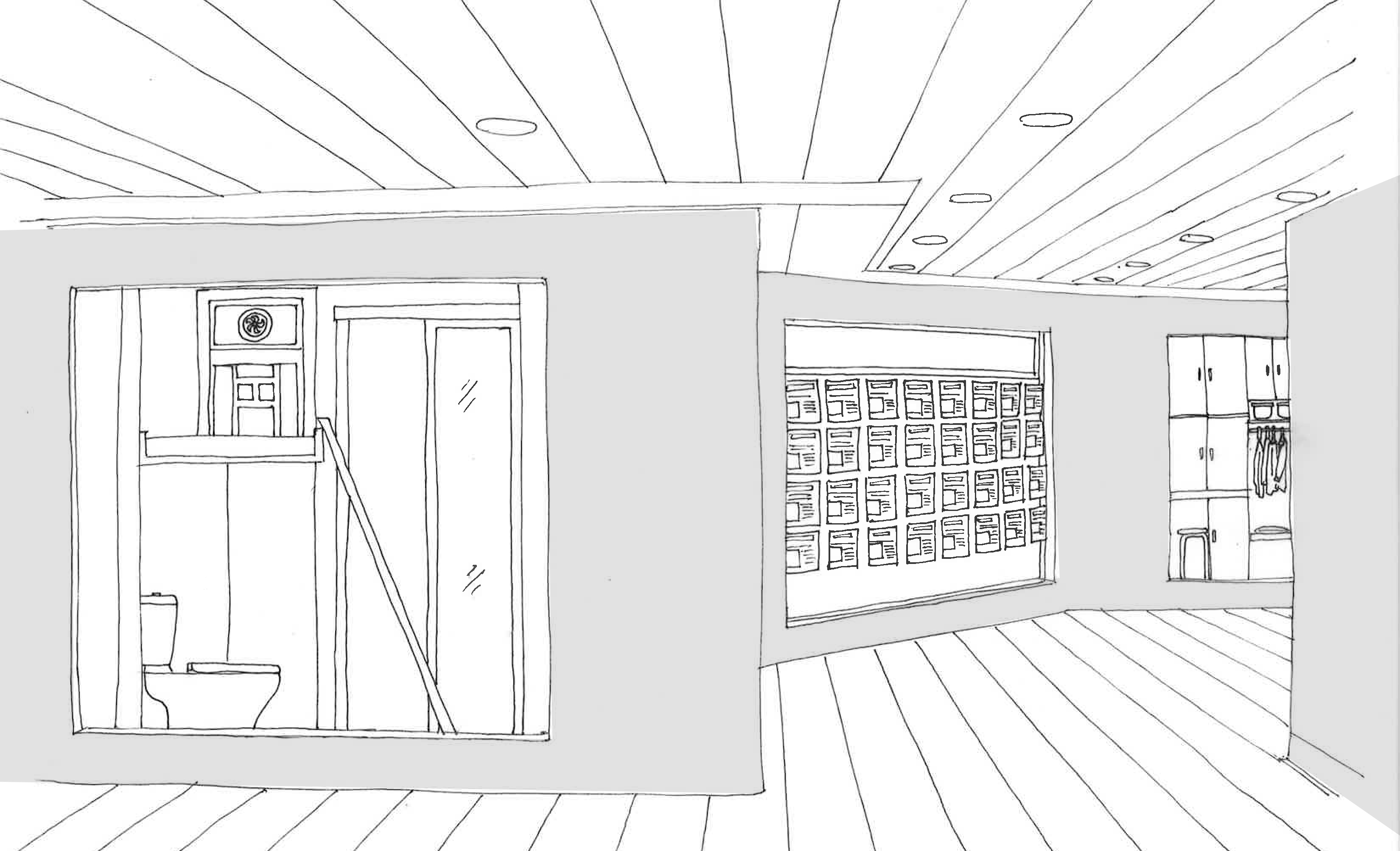

How to Make Space presents three artworks that highlight the spectrum of spatial experience of MDWs in Hong Kong, acknowledging the relationship between identity and space. Suitable Accommodation, by architect Tings Chak, includes 1:1 illustrations of the various living spaces assigned to MDWs according to the ambiguous requirements outlined in the standard employment contract, inviting us to consider how the definition of 'habitable' may be conveniently changed depending on who is being housed. Devora Neumark's Letters of Gratitude recognizes the shared terrain of the household as simultaneously a workplace for the MDW and a space of leisure and refuge for the employer's family. The letters act as a distancing tool, providing a space for communication between employer and worker, While their public display as posters brings visibility to positive stories that are rarely heard in the media. Stephanie Comilang's sci-fi inspired video Lumapit Sa Akin, Paraiso (Come to Me, Paradise) eschews the construct of the generic 'user,' navigating the urban landscape from the MDWs' point of view. Together, the artworks illustrate that physical space is not a neutral platform for events, but a discursive site that is inextricably linked to identities and that can give rise to conflicting interpretations of who has the right to claim space and decide how it can be used.

These projects add context to the Sunday phenomenon, recalibrating our expectations about who has, or should have, the authority to shape the city. The MDWs' refusal to be defined only by their domestic labour and the architectural agency they demonstrate by inserting a quasi-domestic sphere into public space constitutes a pragmatic and political disruption of the status quo. By making permeable the borders between public and private, commercial and domestic, and inside and outside, the women re-order public space. Their actions both critique the existing city and offer a proposal for how it could be reformed, making and an important gesture toward the possibility of a feminist architecture.

Jennifer Davis, co-curator

Su-Ying Lee and Jennifer Davis © 2016

Contain yourself (women). If not plainly stated, this expectation is made explicit in the ways that women are judged and defined. Though this manifests differently across cultures and geography, a distinct type of derision is cast upon women who indiscreetly take-up space. Not only is the space occupied by her body contested, but also the vocalization of her opinions, assertions of intellect, demonstrations of ability, and expectations for recognition.

| Some ways for women to be in public | |

Legitimate - Heading to a destination - Shopping - For 'professional' reasons - By belonging to someone: Caring for a child/care-giving, accompanying a male partner |

Illegitimate - Aimless - Idle, passing time - Sex work - Visibly queer - Loitering |

In 2014 I visited Hong Kong, and while wandering around on a Sunday, I was surprised to see multitudes of women on and around public spaces purposefully demarcated with tarp and cardboard. Although I recognized the rituals of weekend socializing, the epic proportions of exclusively female groups sharing foods, grooming, and worshipping in public is distant from my own experiences. The women, I later learned, are Migrant Domestic Workers (MDWs). Where I am from, women do not take-up space this way.

I am Chinese, but the context of my formative years, socialization, and education is Canadian. At home in Canada, I am part of continual conversations about what it would take to make space for women in the work place, social sphere, academic world, various fields of practice, and with one another, as allies countering a dominant culture. On occasion, a woman will recount an incident when she was given space but, more often, women relate meeting opposition in their struggle for space. For these reasons, witnessing the MDWs taking-up the space they need struck me as a noteworthy achievement.

My own preoccupation with female agency over space and the consequences of women's visibility led to considering the strategies being employed by MDWs and their effects. Through research undertaken by myself, co-curator Jennifer Davis, and artists Tings Chak, Stephanie Comilang, and Devora Neumark (in collaboration with Open Door and Rowena Yin-Fan Chan), How to Make Space approaches the matter of how the visibility of women is met.

Predominantly from the Philippines and Indonesia, over 300,000 women have migrated to Hong Kong for domestic or care-giving work. MDWs are required to reside with their employers, compounding the vulnerability of their positions created by restrictive government regulation of their movements and terms of employment. In the population-dense city, where surplus space is unlikely, guidelines governing conditions for domestic workers are loosely regarded and largely unmonitored by officials. It is not out of the ordinary for sleep accommodations to be in the living room, bathroom, kitchen, corridors, in their charge's bedrooms, on tables, appliances, balconies, and worse. Profoundly, MDWs perform vital roles while expected to be otherwise imperceptible, at once allowing their female employers to increase their own social presence and engage in pursuits outside the home. Under such strictures, it stands to reason that the women are literally 'uncontainable,' spilling out into the space of the city on Sunday, their only weekly 'holiday,' equipped with belongings typically considered personal and domestic. Their presence is asserted through activities that encompass streets, walkways, and parks with rituals of bodily care, creative expression, performance, religious worship, commerce, and gaming. Scents of food and sounds of shared cultures and languages occupy and energize the environment. These material, visual, aural, and olfactory aesthetics re-form the built environment of Hong Kong and hold a space of self-determination.

During duty hours, 'neutral' dress meets the expectations of paternal or suspicious employers. On Sundays, MDWs dress freely against anxieties and governance over women's sexuality. Autonomous self-fashioning, contrary to normative gender expectations, contributes prominently to the 'queering' of public space.

Within the deliberately designed communities of intermittent architecture, the agenda for the day appears to be leisure. Perhaps less obvious is the effective construction and maintenance of a network of information, resources, and action, both informally and formally organized. Regardless of whether these activities are considered legitimate, the women's occupation of time and space must be considered as their own.

Critics seeking to position the MDWs' presence as a nuisance point to the women's success in permeating public space. These arguments affirm classism, serving to privilege and legitimize other groups' use of civic space. The MDWs' hyper-visibility clashes with perverse expectations that they take-up the labour of care, but do not 'take-up' space in the city, and also highlights the insistence on cheap foreign labour while rejecting foreign bodies.

The women hold strong the practice of assembly against designations of difference and social hierarchy to the effect of complicating characterizations of femaleness. Their refusal to comply with prescriptive expectations on the female body risks being seen as unruly. The refusal to be invisible is radical.

Su-Ying Lee, co-curator

Female Feedback

I'm an architect: the discipline permeates my vocabulary and frames how my colleagues and I see and understand the city. When we design buildings, the people and activities become users and programs. Binaries such as public and private, commercial and domestic, and inside and outside articulate our understanding and approach to organizing spaces at all scales, from a single family home to a city-wide zoning map. Although our terminology can be a useful tool, in using it we risk erasing the specificity of individual experience and the ways identity can influence the built environment.

Unlike most of my architect colleagues, I am a woman. And in the last few years I have been struck by how my discipline, in its parlance and paradigms, negates gender.

I undertook How to Make Space as a journey in self-education. While most North American architects would travel around the world to experience the 'city without ground' of Hong Kong's soaring skyscrapers, I wanted to understand how women in this city enact a kind of architectural agency that I had never seen in my architectural training. Could their tactics of making space be used by other women? What might this mean for the field of architecture? Could their spatial knowledge, fed back in to the architectural discipline, reshape it?

The HSBC bank headquarters in Hong Kong's Central District has been a beacon for architects, financiers, and tourists since it was built in the 1980s. Its high-tech aesthetic, designed by English architect Sir Norman Foster, was intended to be a bold assertion of the economic sophistication and ambition of Hong Kong. The design was featured in television documentaries, heralded in an exhibition at MoMA in New York, and discussed in business journals including the Far Eastern Economic Review:

[Foster's] design keeps the user, not just the developer, in mind. Pedestrian circulation should be good and the building incorporates a major public amenity, a plaza under the building at ground level. (A design so interesting to look at must also be counted as a public amenity.) This open atrium and escalators will make it easier to see, be seen or converse - The good lighting, among other factors, should make it a better place to work. (James Sterngold, Far Eastern Economic Review, 5 July 1984, p.31-32)What a contrast between this image of public efficiency supporting the smooth circulation of money and people and the Sunday scenes in Central and Causeway Bay, when Migrant Domestic Workers install temporary micro-architectures that transform pedestrian bridges and office plazas. The women's ad hoc structures are tactically installed on hand railings, sheltered by outdoor stairways, and nudged up against benches and walls. Inside provisional rooms, they host communal activities typically associated with domestic space - eating, socializing, worshipping, and grooming - carving out spaces of care for their primarily female community.

MDWs are integral to Hong Kong society, yet their spatial experiences are circumscribed by their intersecting gender, national, and class identities. The women's interventions in the existing architecture afford them spaces of human comfort neither found in their spaces of work nor provided by Hong Kong's official city planning.

How to Make Space presents three artworks that highlight the spectrum of spatial experience of MDWs in Hong Kong, acknowledging the relationship between identity and space. Suitable Accommodation, by architect Tings Chak, includes 1:1 illustrations of the various living spaces assigned to MDWs according to the ambiguous requirements outlined in the standard employment contract, inviting us to consider how the definition of 'habitable' may be conveniently changed depending on who is being housed. Devora Neumark's Letters of Gratitude recognizes the shared terrain of the household as simultaneously a workplace for the MDW and a space of leisure and refuge for the employer's family. The letters act as a distancing tool, providing a space for communication between employer and worker, While their public display as posters brings visibility to positive stories that are rarely heard in the media. Stephanie Comilang's sci-fi inspired video Lumapit Sa Akin, Paraiso (Come to Me, Paradise) eschews the construct of the generic 'user,' navigating the urban landscape from the MDWs' point of view. Together, the artworks illustrate that physical space is not a neutral platform for events, but a discursive site that is inextricably linked to identities and that can give rise to conflicting interpretations of who has the right to claim space and decide how it can be used.

These projects add context to the Sunday phenomenon, recalibrating our expectations about who has, or should have, the authority to shape the city. The MDWs' refusal to be defined only by their domestic labour and the architectural agency they demonstrate by inserting a quasi-domestic sphere into public space constitutes a pragmatic and political disruption of the status quo. By making permeable the borders between public and private, commercial and domestic, and inside and outside, the women re-order public space. Their actions both critique the existing city and offer a proposal for how it could be reformed, making and an important gesture toward the possibility of a feminist architecture.

Jennifer Davis, co-curator

Su-Ying Lee and Jennifer Davis © 2016

Rear View (Projects) is Jennifer Davis, an architect, and Su-Ying Lee, a contemporary art curator. Both a curatorial collective and an itinerant site for art, they experiment with unconventional platforms to mobilize new interactions between art, place, and audiences. Recent exhibitions include Flipping Properties, an installation commissioned for a Toronto Laneway designed by architect Jimenez Lai with Bureau Spectacular.

Jennifer Davis practices architecture and independent curating in Toronto, Canada. Her projects investigate the political and social factors that shape the built environment. Davis graduated with a Master of Architecture (2011) from the University of Toronto and participated in Independent Curators International’s curatorial intensive program entitled Curating Beyond Exhibition Making (2012). In the field of architecture she has received numerous awards including the Power Corporation of Canada Award (2010) from the Canadian Centre for Architecture, and has contributed to publications such as Edge Condition (UK) and Canadian Architect. Davis’ exhibition making experience includes positions such as Exhibition Development Assistant for the Canada Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 53rd International Art Exhibition, 2009. She provided architectural consultation and programming for TBD, the Fall 2014 show at the Museum for Contemporary Canadian Art curated by Su-Ying Lee.

Su-Ying Lee is an independent curator whose projects often take place outside of the traditional gallery platform. Lee is interested in employing the role of curator as a co-conspirator, accomplice and active agent. She has also worked institutionally, including positions as Assistant Curator at the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art (MOCCA) and Art Gallery of Mississauga, and Curator-in-Residence at the Justina M. Barnicke Gallery. Recent projects include Céline Condorelli’s (UK) The Company We Keep (2013-2014), an installation at the University of Toronto’s Hart House, and Your Disease, Our Delicacy (cuitlachoche), a year long (2012-2013) residency and garden installation at Hart House by Ron Benner (CA). Currently touring across Canada, the project Video Store, begun in 2010 (co-curated with Suzanne Carte), gives audiences unprecedented access to artists’ videos requesting only a pay-what-you-want ‘rental’ fee. Lee’s exhibition titled TBD (Sep 6-Oct 26, 2014), at MOCCA, was begun as an inquiry into the definition of a museum/contemporary art gallery.

Jennifer Davis practices architecture and independent curating in Toronto, Canada. Her projects investigate the political and social factors that shape the built environment. Davis graduated with a Master of Architecture (2011) from the University of Toronto and participated in Independent Curators International’s curatorial intensive program entitled Curating Beyond Exhibition Making (2012). In the field of architecture she has received numerous awards including the Power Corporation of Canada Award (2010) from the Canadian Centre for Architecture, and has contributed to publications such as Edge Condition (UK) and Canadian Architect. Davis’ exhibition making experience includes positions such as Exhibition Development Assistant for the Canada Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 53rd International Art Exhibition, 2009. She provided architectural consultation and programming for TBD, the Fall 2014 show at the Museum for Contemporary Canadian Art curated by Su-Ying Lee.

Su-Ying Lee is an independent curator whose projects often take place outside of the traditional gallery platform. Lee is interested in employing the role of curator as a co-conspirator, accomplice and active agent. She has also worked institutionally, including positions as Assistant Curator at the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art (MOCCA) and Art Gallery of Mississauga, and Curator-in-Residence at the Justina M. Barnicke Gallery. Recent projects include Céline Condorelli’s (UK) The Company We Keep (2013-2014), an installation at the University of Toronto’s Hart House, and Your Disease, Our Delicacy (cuitlachoche), a year long (2012-2013) residency and garden installation at Hart House by Ron Benner (CA). Currently touring across Canada, the project Video Store, begun in 2010 (co-curated with Suzanne Carte), gives audiences unprecedented access to artists’ videos requesting only a pay-what-you-want ‘rental’ fee. Lee’s exhibition titled TBD (Sep 6-Oct 26, 2014), at MOCCA, was begun as an inquiry into the definition of a museum/contemporary art gallery.