"Histories of decolonization commonly foreground the role of men, yet women’s activities and ingenuity were key for the success of anti-colonial movements that multiplied across Africa following the Second World War. During the Algerian War of Independence, one of twentieth-century’s most violent wars of decolonization fought between 1954 and 1962, women joined the resistance to end the long French rule. Women from different socio-economic, educational, and geographical backgrounds contributed as fighters, nurses, community organizers, educators, and civilians to the struggle for Algerian independence.

If one was to believe official statistics in Algeria, only 3% of all war veterans are women.1 This number gravely underestimates the extent of women’s contributions to the journey to independence and reflects the strict military criteria for gaining veteran status. It predominantly recognizes women who joined the urban guerrilla fighters of the National Liberation Front (FLN), the main anti-colonial faction. Their spectacular actions were famously depicted in Gillo Pontecorvo’s film The Battle of Algiers (1966) which is perhaps best known for a scene in which three women trick French soldiers and plant explosives in public spaces popular with Europeans. Equally important, if less spectacular, was the support for independence offered by women in rural Algeria, who ensured the viability of the resistance by hiding, feeding, and nursing fighters.

In rare instances when women are evoked, they figure merely as symbols of a collective and sacrificial struggle against colonialism, revealing little about how women lived through the Algerian War of Independence. Turning women into icons of decolonization fuels their hypervisibility as image, simultaneously flattening their experiences and subjectivities. After 1962, women’s symbolic potential was marshalled for political ends by the FLN which established itself as the sole political party in independent Algeria. It mobilized the image of the heroic Algerian woman to present itself as progressive and egalitarian – a party of all Algerians. Alternatively, it pictured women as victims of excessive colonial violence that was successfully halted by the FLN. Cast either as heroines or victims, women became relegated to the realm of the symbolic, hindering inquiries into their lived experiences during the war. Not entirely forgotten, but also not fully remembered, women continue to hold a tenuous place within narratives of the war.

Beyond Metaphor: Women and War illuminates this blind spot by showcasing works by five artists that address the heterogeneity of women’s experiences during the Algerian War of Independence. Works by Marwa Arsanios, Kader Attia, Katia Kameli, Nadja Makhlouf and Zineb Sedira are displayed alongside historical photographs and magazines to encourage a more nuanced understanding of the intersections between women’s lives and histories of decolonization.

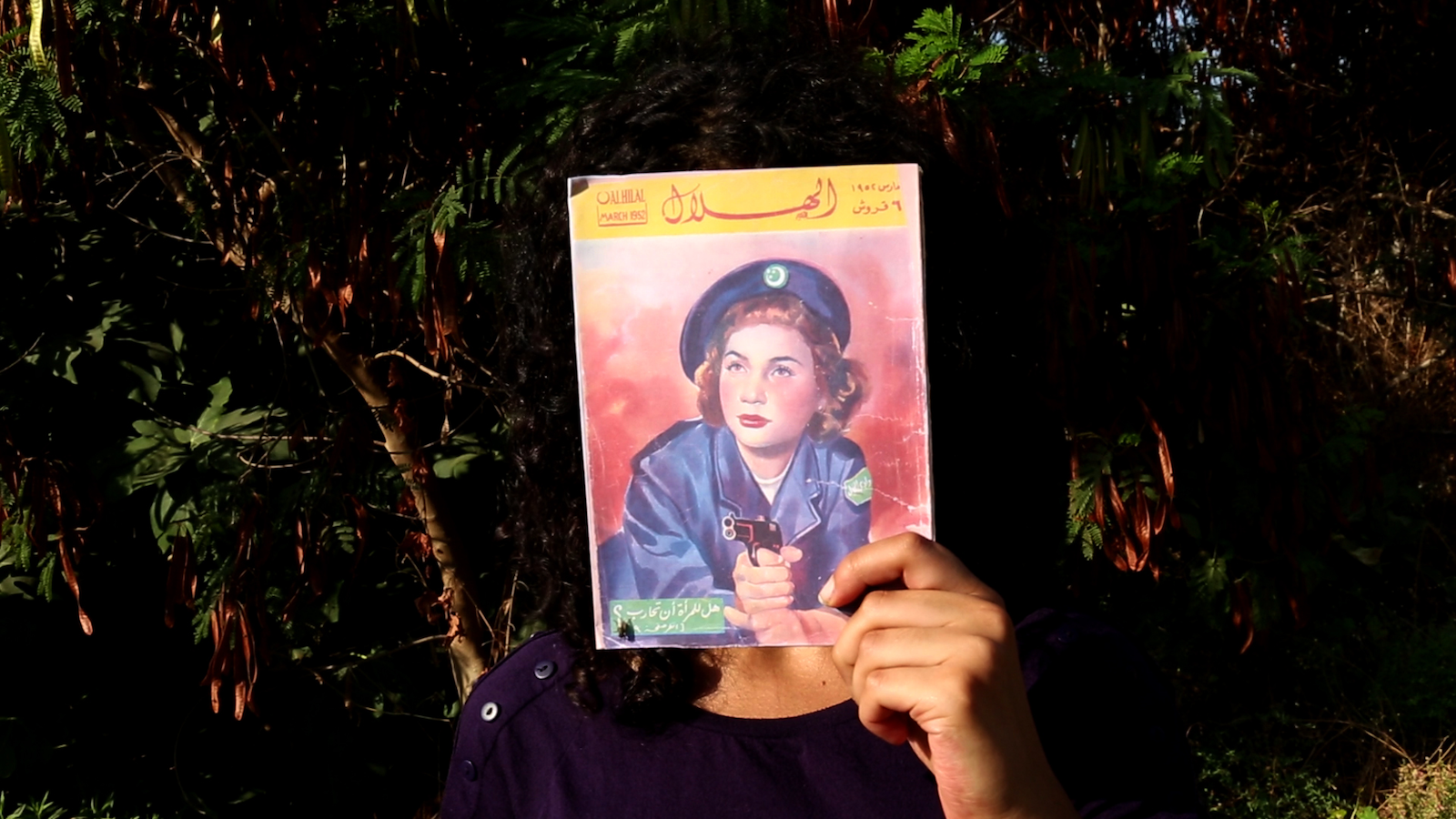

Marwa Arsanios confronts the visual trope of the Algerian woman fighter in her video Have you Ever Killed a Bear – or Becoming Jamila (2013-2014) and artist book Words as Silence. Language as Rhymes (2012). The video’s main protagonist is a young actress asked to play the part of Djamila Bouhired in a film. A member of the Algiers bomb network during the war, Bouhired has become an icon, immortalized through The Battle of Algiers and Youssef Chahine’s Jamila, the Algerian (1958). Her image has equally been adopted on the covers of magazines including the Egyptian Al Hilal (1950s-1970s), which features in Arsanios’ work, and Al Musawar (1958), included in the exhibition as contextualizing material. In the video, the actress makes cautious attempts to embody Bouhired, while remaining hesitant whether to take on this role. Bouhired’s iconic image seems impossible to embody having been subject to so many reinterpretations.

In an effort to approach the historical figure, the actress begins to speak as Bouhired. She does not recall the glory of the anti-colonial struggle, reflecting instead upon gender inequalities in the FLN ranks. “We were not only fighting the French, but also each other,” she states, foregrounding the patriarchal aspects of the liberation struggle – a topic largely marginalized within existing narratives of the war in Algeria. This fictive account resonates with the recollections of veterans such as Fadéla Mesli who recalled that during the war women “led two revolutions, one against colonialism, the other against taboos.”2 Arsanios’ video and artist book form deeply feminist inquiries into processes that turn women into symbols of a gender-blind national unity.

While Arsanios critically revisits Bouhired’s iconic status, works by Kader Attia, Nadja Makhlouf and Zineb Sedira foreground intimate encounters and oral recollections. In Kader Attia’s video Colonial Melancholia (2019), 102-year-old Hadja Hajuna Debba recalls how Algerian women integrated French colonial coins into their jewellery designs as a sign of cultural reappropriation. Debba’s memories of the war are interlaced with her demonstration of how the jewellery was worn: “it was fashionable back then, I swear!” she asserts. She is joined by Attia and his mother who recalls that the artist’s grandmother collected jewellery from women living in the Aurès mountains in northeast Algeria as a way to financially contribute to the anti-colonial struggle. Revealing the oft-unrecognized ways in which women supported the struggle, Colonial Melancholia extends Attia’s long-standing inquiry into colonial dispossession and the potential of reappropriation.

Transgenerational memory transmission also structures Zineb Sedira’s video Retelling histories, my mother told me... (2003) which presents the artist in conversation with her mother, a frequent protagonist of Sedira’s early works. In this single-channel projection, Sedira’s mother recalls how she used to intentionally make her face dirty when French soldiers entered their village to avoid sexually motivated violence. As many historians have noted, rape and torture were unofficially sanctioned by the French military during the war.3 Sedira’s mother further discusses the “collaborators” during the war, the so-called harkis: Algerians who joined the French army, often due to extreme poverty. In Retelling histories, my mother told me... Sedira casts herself as heir to her mother’s gendered recollections of war in a way that is reminiscent of Assia Djebar’s film La Nouba des Femmes du Mont-Chenoua (1977) in which the main protagonist, Lila, speaks to women in her native village about their experiences during decolonization. The word “retelling” contained in the title connotes the malleability of memory and the open-endedness of narratives of war.

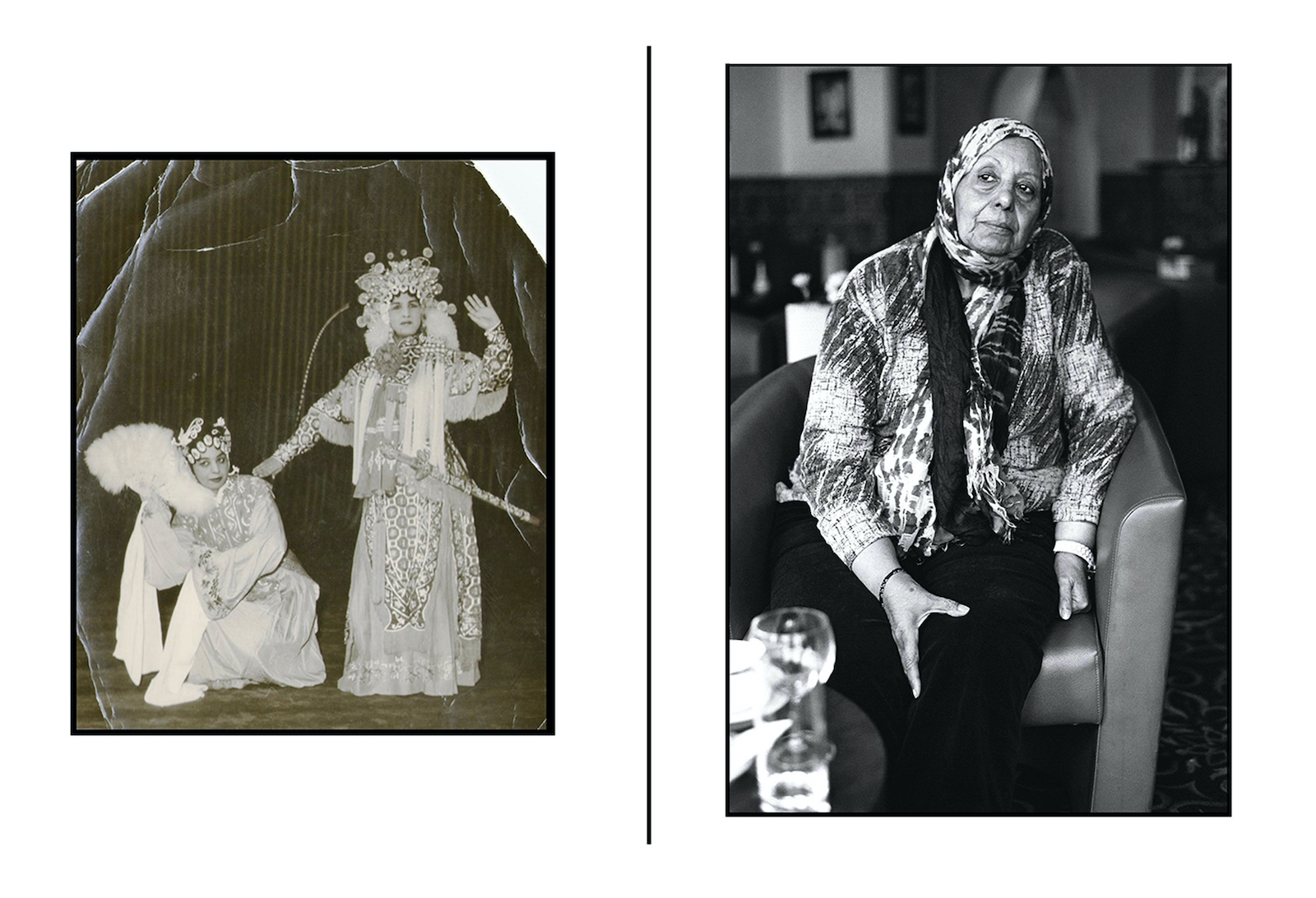

Nadja Makhlouf’s series De l’invisible au visible: Moudjahida, femme combattante (2014) gives a sense of the extent to which women were integral to wars of decolonization. The artist photographed women who fought for Algeria’s independence, pairing these portraits with their historical photographs and short biographies. All historical images were selected by the women from their personal albums, revealing how they wish to remember their contributions to independence.

One photographic diptych features Henda (b. 1927, Algiers, Algeria) who joined the FLN’s artistic troupe in Tunis and performed in the Soviet Union, China, Iraq, and Egypt to raise awareness of the war. The historical photograph pictures her in elaborate costume, likely taken during a performance that began and ended with patriotic songs and the display of the Algerian flag. Other diptychs show Fatima Kade (b. 1923, Algeria) and Aouali Ouici Senouci (b. 1938, Tlemcen, Algeria) in uniforms, revealing their involvement with the maquis (rural guerilla movement). Other allies in the resistance such as Alice Cherki (b. 1936, Algiers, Algeria), a Jewish woman who nursed FLN guerrillas at a hospital run by Frantz Fanon in Blida, Algeria, chose a simple passport photograph. Several diptychs include family photographs that foreground intimate relations, and images that show how traditionally gendered tasks such as sewing were put to use for the making of Algerian flags in the name of the revolution. Notably, the series centers on women who were officially recognized by the Algerian government as war veterans, including French settlers who joined the Algerian resistance.

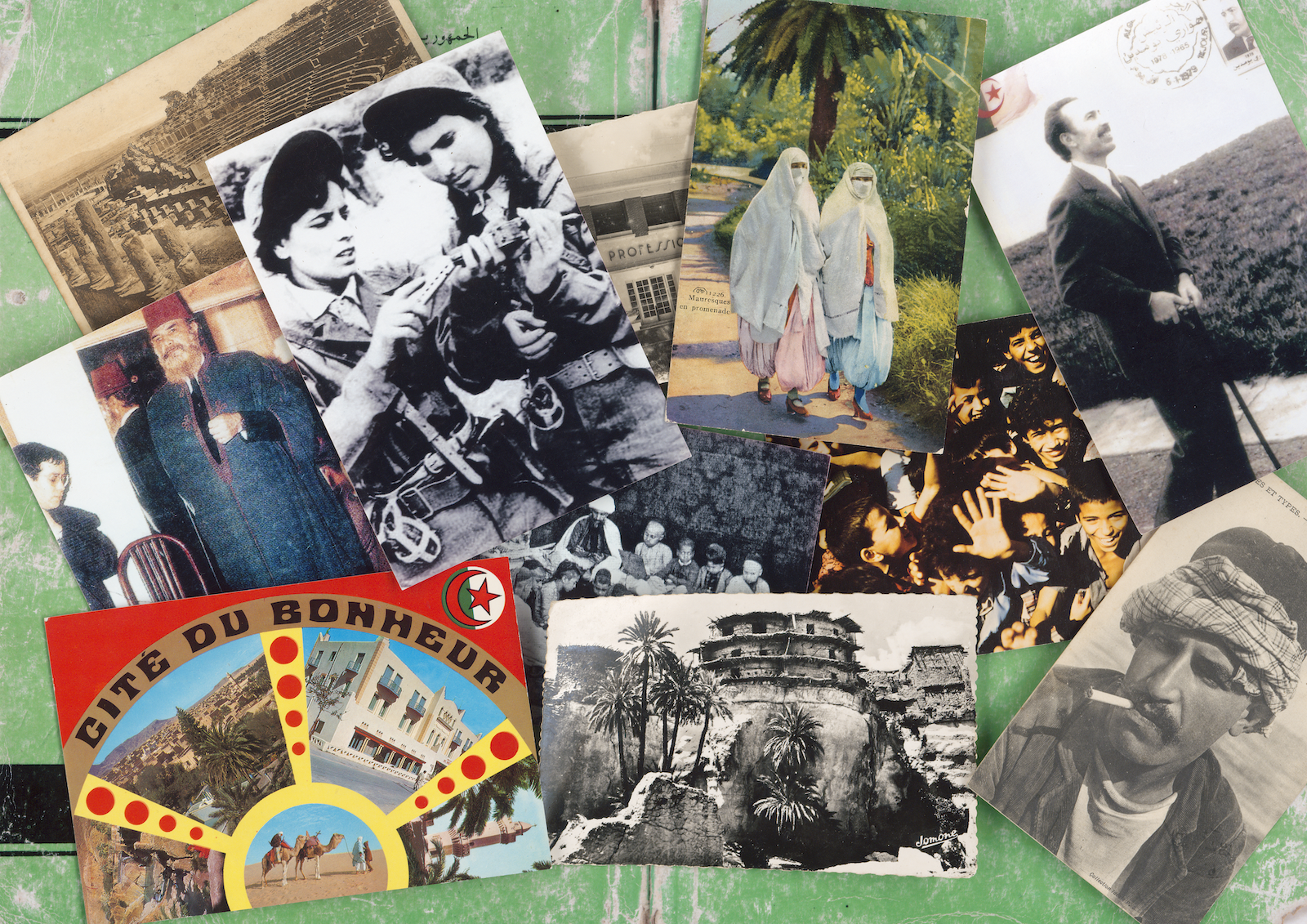

While Makhlouf attends to individual lives, Katia Kameli reflects upon the broader mechanisms of historical writing in her series Soyez les Bienvenus (2018), composed of prints and an animation. Photographs of armed women fighters sit side-by-side picturesque and orientalist views produced by the French, as well as images of Algeria’s second president Houari Boumédiènne and revolutionaries including Che Guevara. The meshing together of different sources does not produce a coherent story of the nation, revealing Kameli’s long-standing interest in the role of images in shaping a collective consciousness. By collaging photographs of women fighters next to those of well-known revolutionaries, Kameli composes a visual mosaic that eclipses a fixed national history and opens up the possibility of writing gendered histories of war.

Mediated through film, literature and art, the Algerian War of Independence continues to shape our collective imaginaries. By foregrounding contemporary art works that attend to women’s experiences during this seven-year-long conflict, Beyond Metaphor: Women and War invites visitors to reflect upon the selective politics of public remembrance and historical record.

Katarzyna Falęcka

Open Call Exhibition

© apexart 2021

1. The records of the Algerian Ministry for Mujahideen (veterans) places the number of women combatants during the war at 10,949. In 2014, Nassima Guessoum made the film 10949 femmes dedicated to women veterans.

2. Fadéla Mesli quoted in Natalya Vince, Our Fighting Sisters: Nation, Memory and Gender, 1954-2012 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015), pp. 96-97.

3. See James D. Le Sueur, “Torture and the Decolonisation of French Algeria: Nationalism, ‘Race’ and Violence in Colonial Incarceration”, in Captive and Free: Colonial and Post-Colonial Incarceration, ed. Graeme Harper (London: Bloomsbury, 2002); Raphaëlle Branche, “The French Military in its Last Colonial War: Algeria, 1954-1962 – the Reign of Torture”, in Interrogation in War and Conflict, eds. Christopher Andrew and Simona Tobia (London: Routledge, 2014).