It is challenging to be a woman in a transitional society. This is true of Iran, where the modernization of political structures, economies, and social values is at odds with tradition.1 Here, as in many places, women must endure dominant and repressive standards of beauty, sexuality, gender roles, and limited social acceptance in hopes that collective consciousness will come to terms with changing global norms. While the difficulty of being a woman in Iran is well recognized, issues of social acceptance are particularly complex and dire for women who have recovered from addiction.

Women who use drugs endure greater stigma and receive far less social support than their male counterparts; they also frequently suffer from domestic abuse, poverty, and prejudice, in addition to physical and mental health issues. Many struggle to express emotion, make meaningful connections with other people, and partake in normal day-to-day activities. Despite all these struggles, familial and societal attitudes towards women with histories of addiction rarely change, even when they have stopped using.

Stranded without adequate emotional, social, and economic support, many of these women face low self-esteem, social isolation, depression, and potential relapse.

WOMEN C(A)REATE is an exhibition of three newly-commissioned textile-based installations made by Iranian women artists in collaboration with women in recovery from addiction and domestic abuse. A fourth artwork in the exhibition is generated from an artist-led collaboration that brings together these recovered women and the general public for a two-day workshop aimed at fostering important discussions on issues of women’s empowerment.

Textile art, the dominant medium of the exhibition, has deep roots in Iranian culture: taking form in carpet design, embroidery, needlepoint, and sewing. Throughout history, textile art has long been excluded from the realm of “fine” art, and has been relegated instead as “women’s work” or “craft.” The 1970s marks a critical turning point for the medium in which artist activists and feminist artists such as Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro pushed boundaries and challenged the traditional definitions of art.

Today, movements like Craftivism explore the possibilities of needlework as a form of gentle protest.

This is seen in the pink hand-knit feline-eared hats that made headlines in the global women’s marches of 2017, and the Chilean Hombres Tejedores, the “knitting men” who challenge patriarchal norms by performing their needlework in public while wearing suits and ties. In the spirit of these diverse and overlapping histories, WOMEN C(A)REATE brings together works which employ or are inspired by textile-based arts, social practice, and art therapy, all in an effort to give visibility, empathy, and voice to one of Iran’s most vulnerable populations.

Homa Delvaray is a visual artist and graphic designer based in Tehran whose sculptural installation Neither Up Nor Down consists of a cylinder hanging from the ceiling and a square surface positioned underneath it. The textile sculpture is covered by fabric emblazoned with poems from ancient Iranian Sufi poets, accompanied by a patchwork of colorful floral and embroidered fabrics, which are hand- and machine-sewn by a group of recovered women. The artist has selected poems which include frequent use of the words “up” and “down” as a way to explore dualities that inform the relationships between oneself and society, such as body and mind, progress and decline, and life and death. They also reflect the continuous “ups and downs” that can be found throughout the history of Iran. The poem’s lines are broken and rearranged, creating a fragmented narrative that is constantly changing its course; sometimes it becomes a voice in the reader’s head, and other times a sermon from the unseen world. The installation draws the viewer’s eyes up and down, and encourages a constant repositioning, which ultimately results in a feeling of suspension.

Maryam Palizgir is an Iranian visual artist and educator based in the United States. Her piece, Intimacy to Vulnerability is a performance installation inspired by the physical and emotional pain experienced by women with histories of struggle. Throughout the performance, participants drive nails into a wooden surface attached to a wooden frame that is covered with sheer spandex fabric.

The piece is symbolic of participants’ experiences and memories with needles and their consequences, inviting viewers to explore the complex contemporary identities of women in addiction recovery.

In pairing soft, delicate, flexible, and seemingly feminine materials of sheer fabric, with rough, sharp, unfinished, and seemingly masculine materials of wood and metal, the project also explores common misconceptions about gender and drug addiction. The collective performance provides its participants with powerful metaphors through which to address their pasts and take control of their lives with tools of creative expression. An edited video of the performance is an integrated part of the art work.

Hoda Zarbaf is multidisciplinary artist based in Tehran, whose installation Anti-home explores the relationship between nostalgia and social isolation. Persistent reflections about former homes, relationships, status, and accomplishments are all symptoms of nostalgia. Returning to her home country of Iran after a decade of residing in North America and following a relationship breakup, the artist was forced to move into a new rental apartment. Throughout this process, Zarbaf obsessively wondered whether she would be able to create a new home, and how would she fill in the blanks between remembering and forgetting, continuity and rupture, or sameness and difference.

To materialize this complicated process of renewal, Zarbaf’s installation manipulates a linear understanding of time wherein the past is forever gone and the future entirely unpredictable. The installation mimics a residential home, in which a TV set plays a video of Zarbaf exploring of her apartment. Screen-shots from the video are found elsewhere in the installation, printed on fabrics that are sewn by recovered women into curtains, cushions, and a kimono—soft forms which call into question their own ability to provide comfort. A blurred video still of a chandelier viewed from below hangs framed, flat against the high ceilings of the exhibition site. An image of the artist’s sofa is printed on cushions that are placed on the couch in the installation, a displacement repeated in undone bed linens and the half-closed shower curtains. An oversized hanging jacket is sewn from fabric printed with the image of a closet—another image still from the artist’s video. The artist’s silhouette in the video is masked and blanked, but she reappears projected in a dark corner of the installation, giving a visual representation to the challenge of grappling with a loss of the familiar (a complicated past) and unknown potentials (future).

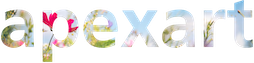

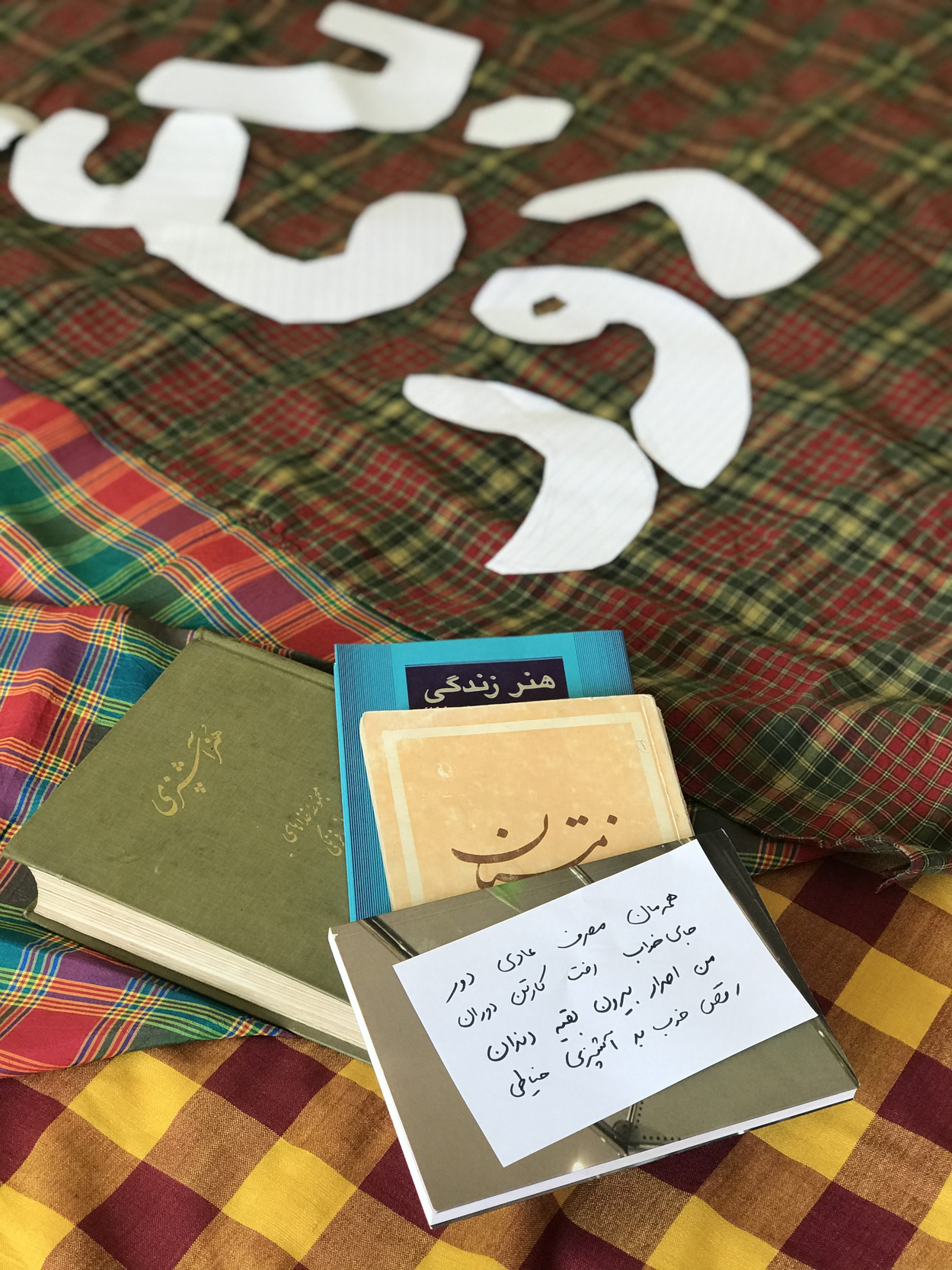

Negar Farajiani is a visual artist and independent curator based in Tehran whose socially-engaged work, Triptych is an installation created through collaborative efforts from women in recovery and the general public. The participants work together towards a common goal, to raise awareness and provoke productive conversations around the social status of women, and find new modes of affinity and understanding through a creative exercise. As a creative prompt for all participants, Farajiani reads well-known stories and poems from Iranian literature. The stories examine social dilemmas stemming from traditional values and cultural norms pertaining to gender, initiating a collective conversation and encouraging participants to share their own perspectives and experiences as they relate to the stories. Farajiani visualizes their conversations and selected poems by applying embroidery and patchwork to different shapes and patterns of fabric, which the participants will later sew together as three curtains based on the artist’s guidance. The resulting work will be auctioned off during the exhibition, with proceeds going to Iranian NGOs and associations dedicated to issues of women’s empowerment and education.

As Tom Finkelpearl outlines in his book What We Made: Conversations on Art and Social Cooperation, social practice is “art that is socially engaged, where the social interaction is at some level the art.”2

WOMEN C(A)REATE is an assemblage of possibilities reflecting the coexistence of diverse identities and experiences in a dynamic and diverse society. It presents works which employ social practice and alternative forms of art therapy to provide recovered women with creative healing opportunities, a sense of purpose, and accomplishment. The motivating factor propelling the exhibition is a collective effort towards female empowerment. By encouraging social inclusion of recovered women, and providing opportunities for them to take an active part in the public sphere, WOMEN C(A)REATE acts as a tool for collective empowerment, action, expression, and negotiation.

Anahita Rezaallah and Elnaz Tehrani

Open Call Exhibition

© apexart 2020

1. I.A. Reed and J. Adams, “Culture in the transitions to modernity: seven pillars of a new research agenda,” Theory and Society, 40 (2011), Accessed 4 January 2020, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11186-011-9140-x.

2. Tom Finkelpearl, What We Made: Conversations on Art and Social Cooperation (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013).