Art transcends borders–until it doesn’t.

In 2016, Ahmad Hammoud’s project Passport for the Stateless returned from an exhibition in Dubai to its origin in Cairo, and though the artwork’s central piece resembles a passport, it is obviously not a valid travel document. Yet, before it was allowed back into the country, Egyptian customs drew deep lines of red ballpoint pen across the booklet’s 32 pages and nearly tore it in half. When he discovered the work’s severely damaged condition, curator Mohamed Elshahed posted a picture on social media and succinctly concluded that this violation was “probably the best illustration for what (Hammoud’s) project is about.”

The story resonated but it also didn’t come as a surprise; over a decade of working in the arts in Egypt and the Gulf meant that I’d seen sculptures emerge from shipping with serial numbers and signatures scrawled in permanent marker across otherwise pristine surfaces; works on canvas and paper suffering tears, slits, and punctures; photographs and oil paintings damaged by prolonged exposure to heat; tracking numbers leading nowhere; and shipping containers transporting whole exhibitions mysteriously and irretrievably lost. Based on personal experience, negotiating this uncertain circulation permeates just about every aspect of working in the arts within the Middle East and Northern Africa (MENA) region.

Reflecting on these circumstances led to conversations with artists who spoke generously of their experiences but often off the record due to a mix of social, political, and professional pressures. One artist critiqued the premise that there exists any relevance within or beyond the damage, and another didn’t want their work to be associated with its loss. Others welcomed the occasion to tell their stories publicly or to broach the general issue of the arduous circumstances that inform the precarious mobility of their creative work. Travel was also a frequent topic, specifically the discrepancy between the theoretical ability of artworks to cross borders while visas are typically denied the artists who create the works–a trend this exhibition was unable to break. Throughout these discussions it also became clear that the unpredictable outcome of surrendering artworks to shipping and customs can yield grave psychological repercussions. Effects range from a total creative block following the acceptance that a body of work has become lost or damaged beyond repair, to a subtler self-censorship that manifests over time, sometimes as an unwitting retreat into increasingly abstract imagery, or in the form of a pragmatic approach to making art that preempts travel related obstacles. With visual arts, this can mean shifting to digitally-transferable works, or making objects that deliberately fit into a suitcase to facilitate transport by commercial airlines, or strategizing around re- assembly or reproductions on the other side of a border.

With governments worldwide becoming increasingly focused on subversive movements to the point of defacing anything that looks unusual or unfamiliar, the circulation of art–like everything else that crosses borders–falls under higher scrutiny, especially when art’s esoteric qualities elude a standard interpretation of value and meaning. Presenting a range of works by artists with deep connections to Egypt, Iran, Jordan, Kuwait, Palestine, and Tunisia, and works impacted by travels through other parts of the MENA region, Occupational Hazards addresses how artworks become subject to overzealous vetting systems–whether by deliberate force or through passive negligence–and in some cases, how artists are able to reclaim agency despite these circumstances. In addition to works damaged or destroyed while going through customs, the exhibition shows examples of works which have been reformatted post-incident to incorporate and accommodate damages; works that, though forbidden or mired by bureaucratic hurdles, have made it across borders; and works that incorporate incidental or intentional damages as a conceptual underpinning. In its entirety, Occupational Hazards showcases ways that artists are enduring, responding to, and circumventing the consequences of contemporary cross-border travel.

Participating artists Huda Lutfi, Aissa Deebi, Shuruq Harb, William Andersen & Maryam Hosseinnia, and the aforementioned Ahmad Hammoud have all found ways to reclaim agency following significant damages in their works. The resulting artworks that are featured in the exhibition have been revisited by the artists–each of whom asserts their creative liberty to decide the final iterative forms and contexts in which their works are to be seen. Huda Lutfi’s installation derives from her 2003 work Carpet of Remembrance, which featured wooden shoe-molds inscribed with Sufi proverbs. While being shipped to Bahrain for an exhibition in early 2005, the work was confiscated by Cairo airport officials and deemed religiously offensive. Interrogations followed, where the works were misinterpreted as being an exploitation of Islam, a religious conspiracy, and a threat to national security. The charges were dropped but the work remains stored in the airport’s warehouses. Lutfi also presents one originalTahrir Portrait (2013) from the series that was originally exhibited during a short period of lax censorship in Cairo and one new, incomplete version entitled Occupational Hazard (2019). The original, completed work cannot return to Egypt due to its portrayal of Egyptian police officers while the latter, half-finished version shows the limits of what is now permissible for safe export. Aissa Deebi’s This is How I Saw Gaza (2017) is a series of oil paintings that investigate the artist’s relationship with his homeland.

They were severely damaged in 2018 en route from Dubai to Geneva, but he has since constructed new works from the canvases that could be salvaged. Shuruq Harb revisits The Keeper (2013), a work with 2,000 photographs at its core, which the artist inherited from a young entrepreneur who collected images online to be printed for sale on the streets of Ramallah. In 2014, as her work was being shipped from New York City to Amman, it was confiscated and later released by Jordanian Intelligence due to the political nature of some of the photos in the collection. Rather than display the work in its original installation format, Harb shows a photograph of the boxes that were damaged through this process of interrogation, alongside the original video. Three years later, William Andersen lost almost two decades worth of irreplaceable artworks, 29 pieces in total, as they were shipped back to Kuwait from China following a solo exhibition, coincidentally titled No Way Home. Now and in collaboration with Maryam Hosseinnia, he is beginning to make art again, starting with كفن shroud 裹屍布 (2019), a reinterpretation of his missing mixed-media textile works. Ahmad Hammoud displays his aforementioned Passport for the Stateless (2016) for the first time since it incurred severe damages at the hands of customs agents.

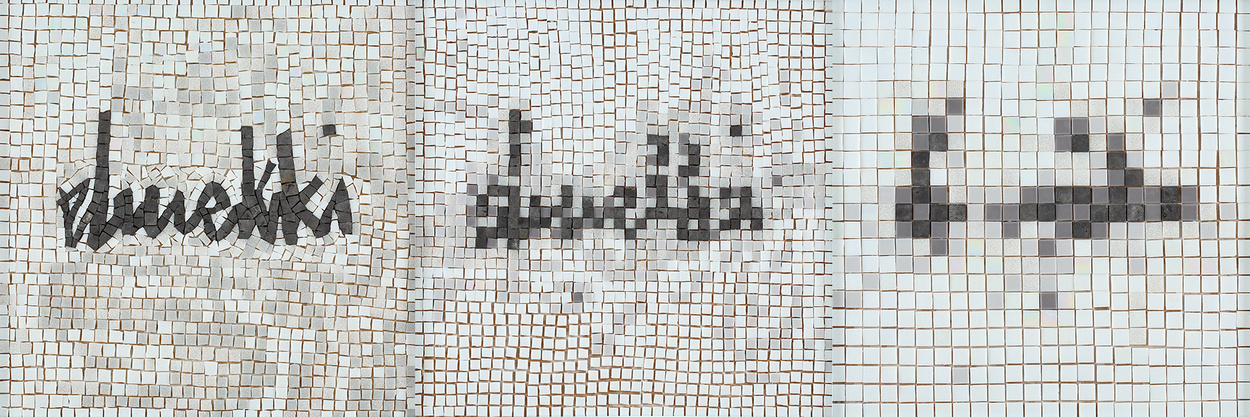

Artworks by Mohamed Ben Soltane, Yassin Mohamed, Negar Tahsili, Amir Farhad, and Carol Mather are presented in two states. Mostly in their original form, they occupy the space as artworks, while they are also an acknowledgement of the highly particular and unlikely circumstances that govern their movement across borders. Mohamed Ben Soltane’s mosaic triptych Contre l’Oubli (Hommage é El Mekki) (2019) is dedicated to the prominent Tunisian painter Hatem El Mekki (1918–2003). The three panels show El Mekki’s signature, first in sharp relief and then fading away, a fate that Ben Soltane says befalls even the best artworks in Tunisia due to lack of reflection on the country’s art-historical past and a dearth of exchanges with regional and international dialogues, which is why the extensive bureaucratic paperwork required to export this piece is also incorporated into the installation. Yassin Mohamed is carving out a name for himself as a “prison artist” whose high-profile case cost him four years behind bars for a crime he did not commit. Some of his drawings, however unlikely, remained from this time despite containing daring imagery– one, for example, depicts a prison guard, while a later work shows a nude self-portrait.

Because they were smuggled out of prison and due to their content, respectively, it is too dangerous to transport his original drawings in any direction, so reproductions are made outside of Egypt and exhibited instead. Negar Tahsili is represented with drawings from her ongoing series B+ (2008–) that are made of ink, colored pencil, and–while perhaps not obvious at first–the artist’s blood. They reflect the informal and rampant organ trade in Iran that is facilitated by social media, representing a dark side of mobility. The work on view, however, is incomplete because as an Iranian artist on a residency in Tunisia, the likelihood of being granted a visa to travel to New York to perform the work’s accompanying interactive component is incredibly unlikely. To facilitate transport, the drawings themselves have previously been couriered with the help of a diplomat. Iran-based artist Amir Farhad tried sending a series of his erotic drawings through the mail but was turned away because of their content. He then covered the explicit parts in black spray paint, “destroying them” on his own terms, but thus also enabling the works to be shipped abroad. This is a variation of a technique he previously applied by temporarily covering nude paintings with white gouache and Arabic calligraphy. Contrasting the severity of some stories is the anecdote around Carol Mather’s brass and enamel brooch of a mermaid that was featured in the British Council’s 1992–1997 touring exhibition All that Glisters, curated by Muriel Wilson. In 1994, when the 90 works in the exhibition returned from Bahrain’s National Museum to London for condition checking and refurbishment, Mather’s bare-chested mermaid was found wearing a new bikini top made of Elastoplast.

Karin Sander, Walead Beshty, and Khaled Hourani have each found ways to evade the uncertainty of international travel, and instead actively utilize the risky aspects that many artists and travelers aim to avoid. Karin Sander’s ongoing series of conceptual Mailed Paintings (2004–) consists of unprotected stretched canvases in various shapes and sizes that are mailed to multiple cities around the world, all the while accumulating markings and traces of their travels on the otherwise blank white surfaces. Exhibited inOccupational Hazards are works that have passed through the Middle East specifically. Walead Beshty’s FedEx box series (2005–2014) is composed of glass sculptures made to fit perfectly inside the proprietary dimensions of said boxes. Designed to crack, these works maintain a critical tension between conforming to a corporate definition of space and performing agency over these limitations. Khaled Hourani’s seminal 2009–2011 project Picasso in Palestine brought Picasso’s 1943 painting Buste de femme to Ramallah for an exhibition at the International Academy of Art. While the painting was on display, Hourani photographed the two local guards responsible for protecting the work. This image of the painting in the middle and two men on each side has evolved with every new presentation of the work. As new local guards are photographed flanking the last photograph taken, the original Picasso is now but a speck in the background. In the context of this exhibition, Hourani’s method of mocking bureaucratic limitation is an illustration reflective of the exhibition as a whole.

Alexandra Stock

Open Call Exhibition

© apexart 2019