Climate migration is not a new phenomenon. Ancient civilizations were resilient, adapting to climatic shifts and developing ability to live in variable environmental conditions. Displacement and reorganization were common in their societies as a means of addressing destructive environmental conditions such as droughts, floods, rising sea levels, and high temperatures. Ancient documents provide examples of how their institutions mitigated against the effects of food and water shortages. They also reveal migration patterns that indicate human settlement has long been driven by environmental conditions.

In Meteorologica (350 B.C.E) Aristotle1 provides an empirical explanation of meteorological phenomena as part of his larger project of examining the universe. His observational study attempted not only to offer a better understanding of the natural world but also recognise the limits and boundaries of human knowledge and control. Such examinations of the weather and other natural phenomena—astronomical, geological and seismological—have since informed migration patterns, climate adaptation and mitigation, and formed the basis of the modern Western science of meteorology. While this knowledge was sufficient until recently, today’s anthropogenic climate disruption demands the consideration of alternative systems of knowledge; in particular “indigenous or traditional knowledge could be proved useful for understanding the potential of certain adaptation strategies that are cost-effective, participatory and sustainable.”2

Along Thailand’s Andaman Sea coast, three different tribes are famous for living on and from the sea. The most well-known are the Moken. They live on boats and navigate the waters between the southern regions of Myanmar and northern parts of Thailand. Another group is the Moklen, who are only found in Thailand. Dispersed throughout small villages between the many islands along the coast, they settle between the mangroves and the sea and use local resources to sustain their community. Living a similar existence as the Moklen, the third tribe Urak Lawoi’, also known as Orang Laut in Malay, reside on the Thai islands of Phuket, Koh Phi Phi, Koh Jum, Koh Lanta and further south in Koh Lipe.

MAP Office’s project Learning from the Gypsies—which includes sculptural installations, video, postcards, and a map—approaches the ecological knowledge of an indigenous community through the interpretation of one member’s personal story. Gung is a member of the Urak Lawoi’ tribe, which roughly translates as “brother from the sea.” His life experiences have allowed MAP Office to trace a contemporary history of the region, especially regarding the policies implemented to protect its environment and culture: the closure of coal mines, the introduction of blast fishing using dynamite, the establishment of National Parks, the creation of artificial reefs, the establishment of tourist fees and fishing regulations, and the protection of minorities.

Ghost Island is a series of installations set up in various places across Asia—including Krabi in Thailand—that expose the ecological impact of fishing activities on marine life. An accompanying digital video of the same title presents a fictional story in which Gung builds and inhabits one such Ghost Island to stage different moments of an almost-aquatic everyday life. Revealing challenging living conditions and survival tactics, it portends a future where such adaptations must be made. The project also includes Gung’s Nautical Map, which provides a territorial representation of the island, its economy and ecology, as well as a postcard series depicting the Ghost Island as a tourist attraction. Rather than solely serve as an anthropological survey of the Urak Lawoi’ community, the project tries to imagine the limits of human adaptation under increasingly adverse conditions, while disseminating valuable indigenous knowledge that encourages ecological thinking and strategies of coexistence, all through the personal and yet speculative story of a local fisherman.

Climate-induced migration is a phenomenon that will increasingly affect communities and individuals worldwide. Coastal regions such as the Maldives in the Indian Ocean, Sundarbans islands in the Bay of Bengal, Tuvalu in the South Pacific, the Alaskan coast and many more are threatened by rising seas, putting their governments and communities under pressure. However, dealing with changes requires more than regional spatial strategies and solutions. It demands economic and social reorganization and a major retooling of our economies, institutions, and infrastructures, all on a global scale.

Contrary to mainstream visual representations of vulnerable communities at risk, this exhibition urges a radical collective re-thinking of the way we act upon climate change as planetary citizens. Far from promoting planetary catastrophism, exotic miseries and passive resistance, the exhibition aims at raising awareness of climate injustice, challenging the dominant political power of the countries and corporations which are primary contributors to climate change in an effort to foster what T.J. Demos describes as “forms of agency in the present that define a politics of resistance to the fossil fuel economy driving climate change.”3

Kivalina is an Iñupiat village of 400 people situated on a barrier island in the Arctic, on the Northwest coast of Alaska. In 1905, the Bureau of Indian Affairs forced the Iñupiaq to settle there and abandon their territories and long-established patterns of seasonal migration. In recent years, global warming has been delaying the formation of sea ice, exposing the shores of Kivalina to autumnal sea storms and thus placing its very existence under threat. Beach erosion and flooding has rendered Kivalina’s basic infrastructure and habitat vulnerable, pushing the community to seek relocation. This is made more difficult by the fact that the inhabitants of Kivalina do not have legal title over their own land.

In 2006 the town of Kivalina sued the twenty-four largest oil and gas corporations in the world, maintaining that the latter should be held accountable for the consequences of greenhouse gas emissions, and contribute to the community’s relocation costs. Following the judicial system’s failure to address Kivalina’s claims, and the standstill of governmental relocation attempts, artists Andrea Bagnato, Daniel Fernández Pascual, Helene Kazan, Hannah Meszaros Martin, and Alon Schwabe travelled to Alaska and developed the project Modeling Kivalina.4 They have conducted a series of interviews with Alaskan coastal village residents, scientists, and political representatives, and produced film and architectural models visualising the complex political, legal, and environmental transformations operating within the community in support of an effective communication between multiple stakeholders. The work chronicles Kivalina’s ongoing struggles with climate change due to their lack of supporting infrastructure and inability to relocate. It functioned as a tool for activating regional and global conversations around continuous violations of indigenous people’s rights, advocating equality and civil justice.

By mapping out the ecologies of oil and water in two seemingly distinct locales, Ursula Biemann’s Deep Weather reveals the irreversible damage that humans inflict on Earth as a result of reconfiguring its interconnected physical and chemical composition. Narrated from the imagined perspective of a wind travelling between the two ecologies, Deep Weather shows how the uncontrolled, profit-driven extraction of fossil fuel in the boreal woods of Northern Canada correlates with the rising sea levels in the Bangladeshi Delta, constantly redefining the life of its inhabitants in an unending, unjust struggle for survival.

The first part of the video essay titled Carbon-Geologies begins with aerial documentation of the huge open pit that is the extraction zone in the tar sands of Northern Canada. As global oil reserves are gradually depleted over time,5 ever dirtier, remote and deeper layers of carbon resources are sought out. Aggressive mining, steam processing, and evacuation of the tar-sands are impinging on environmental and human rights as they devastate territories of Canada’s indigenous populations.

The second part, Hydro-Geographies examines how the melting Himalayan ice fields cause rising sea levels and extreme weather events that increasingly define the amphibian lifestyle imposed on coastal Bangladeshi populations. The video-essay documents the community-wide efforts to manually build protective mud embankments, as mechanical excavators are a rarity in the deltas of the global South. These are the extreme but necessary measures taken by those who have no choice but to prepare for when large parts of Bangla will be submerged, and water is declared the territory of citizenship.

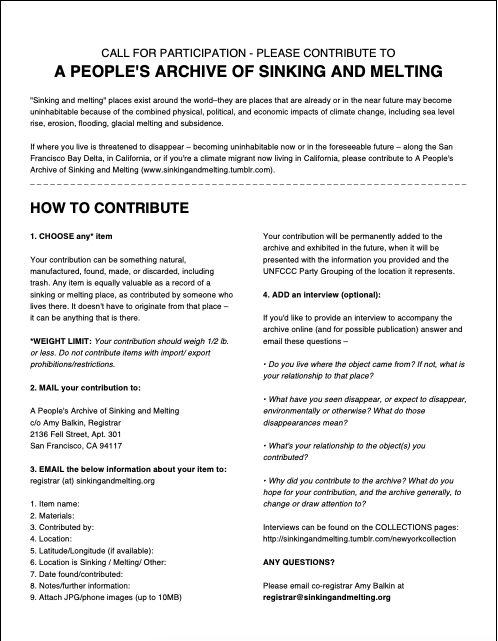

Amy Balkin’s A People’s Archive of Sinking and Melting is a growing collection of items contributed by people living in places in danger of disappearing due to climate change impacts: sea levels rising, coastal erosion, desertification, and glacial melting. Together, organized in distinct collections, these contributions form an archive of the future anterior; what will have been. “Future anterior,” in this case, presumes that the political change necessary to overcome predicted events will not be achieved, and that the places from which people have sent things will disappear. It also assumes the continued existence of an institutional framework to present the archive, as well as an audience able to view it. The project thereby forces audiences to reckon with how communities and nations are already planning for an assumed inevitable: loss of habitable space, attendant migrations, and the violence of militarized resettlement.

The archival collections operate as material evidence of slow violence, precarity and anticipated displacement within communities impacted by environmental adversity. While documenting the geopolitics of climate change and the numerous spatial transformations, the archive also acts as a symbol of collective political action. Individual contributions form a global assemblage of objects that bear material witness to man-made disasters.

With contributions from places of inter-related climate change risks such as Anvers Island (Antarctica), Cape Verde, Cuba, Greenland, Kivalina (Alaska), Miami, Nepal, New Orleans, New York City, Panama, Peru, Russia, Senegal, Trinidad and Tobago, and Tuvalu, the archive recognizes the value of these objects as records of areas threatened by climate change. Local residents can contribute lightweight objects—including remnants, flotsam or jetsam—that “happened to be there” with a description of the ways that climate change has affected the place, whether through sinking, erosion, desertification, or rising sea levels.

Marianna Tsionki

Open Call Exhibition

© apexart 2021

1. Aristotle, Metereologica, Loeb edition, trans. by HDP Lee (London: Heinemann, 1978).

2. D.J. Nakashima, et al, Weathering Uncertainty: Traditional Knowledge for Climate Change Assessment and Adaptation (Paris: UNESCO, and Darwin: UNU, 2012), 24.

3. T.J. Demos, “Climates of Displacement: the Argos Collective’s Maldives,” Altern Ecologies: Emergent Perspectives on the Ecological Threshold at the 55th Venice Biennale, ed. Taru Elfving and Terike Haapoja (Helsinki: Frame Visual Art Finland, 2015), 44-57.

4. The Modeling Kivalina project was initially developed within the Centre for Research Architecture, Goldsmiths, University of London under the umbrella of Forensic Architecture. Fieldwork in Alaska was done in collaboration with the Re-Locate group and was funded by the World Justice Project. The film Kivalina: The Coming Storm was originally commissioned by the Haus der Kulturen der Welt for the exhibition Forensis (2014), curated by Anselm Franke and Eyal Weizman.

5. K. Aleklett, “Peak Oil” In: Peeking at Peak Oil (New York: Springer, 2012)