In the exhibition Altered After, curated by Conrad Ventur (July-August 2019, Participant Inc., New York), California-based artist Julie Tolentino showed a piece titled Harvey, a living cactus with small offshoots planted in a tiny pot and placed on a transparent plexiglass pedestal. Tolentino revived the plant, which had been propagated from its “mother” plant and had originally belonged to Harvey Milk. It was a gift from her friend, an archivist in the special collections at UCLA who acquired the cactus from one of Harvey Milk’s ex-roommates in San Francisco. I was first struck by how this artwork poetically connected the lives of people from different generations and different locations. And yet, what moved me was the care and affection demonstrated through this plant; Milk’s ex-roommate took care of this cactus for years after Milk’s assassination, and Tolentino saw it as a form of inherited knowledge and memory that should be shared.

A few years ago, I had a similar experience when I discovered a collection of diaries, scrapbooks, and scripts at QueerArch in Seoul, donated by a transgender woman in 1998 who visited the office of BUDDY (1998-2003), one of the first gay and lesbian magazines in South Korea. She had been introduced to the magazine through a popular night-time TV program months before. The collection of materials—diaries full of hardship, self-hatred, hopes of transitioning—also included multiple drawings by the donor, mostly self-portraits of the body she desired to have. While the drawings were beautiful in their own way, her touches, her desires to be recognized and remembered, and the materials that connected us across time and space were deeply moving and palpable.

QueerArch (also known as the Korea Queer Archive), was established in 2002 with a donated collection from BUDDY and is the only public archive focusing on queer history and culture in Korea. Currently located in a modest office in the Mangwon-dong area, its collection includes thousands of publications, over 700 films from the Seoul Queer Film Festival, and hundreds of artifacts. While the archive is run by a trained archivist and is well-cataloged online, it does not always adhere to conventional processes of archiving—qualifying, surveying, collecting, displaying—rather, it is a collection of donated objects with chronological gaps and holes, impacted by the notion of contradiction, such as the personal and the public, the organized and the random, the authored and the unknown.

The exhibition QueerArch features new works by five young queer artists and artist groups based in Seoul. It was created after their months-long research at QueerArch with the following questions in mind: how do we challenge the narrow and biased Korean (art) historical perspectives and resist the discursive and academic violence that has resulted in the historical erasure of queer people in Korea?

How do we honor the lineage and history of queer people in Korea and successfully create narratives through the artwork?

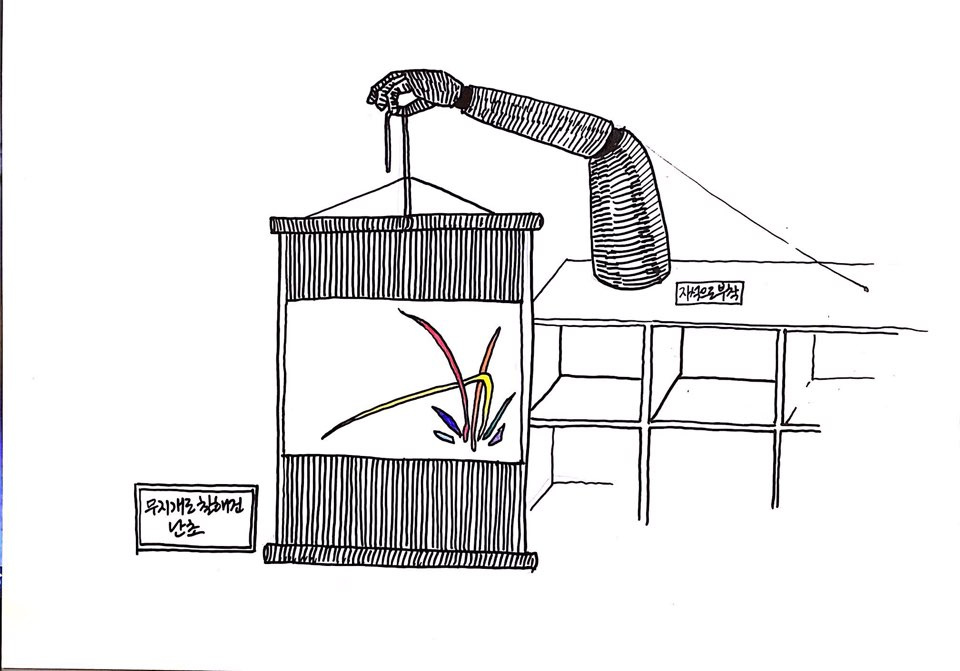

Haneyl Choi’s response to these questions is a thoughtful and selfless gesture of care. Choi, known for his ambiguous and idiosyncratic large-scale sculptures and installations that are injected with sexual fetishes and fantasies, here employs the simple form of a display system as his medium—powder-coated steel bookshelves in this case—to replace some of the old wooden ones damaged by humidity at the archive. Seemingly plain and modest, the work (Untitled) is a result of months-long conversations with Ruin, the archivist at QueerArch, to find the best way to store and display the collection. However, Choi also elevates these functional sculptures to address entire bodies of missing histories by attaching a sculpture of a human arm which displays a hanging scroll painting of an orchid. Appropriating the traditional Seonbi practice of contemplative Korean brush painting (named for a virtuous Korean scholar), the scroll is playful and imaginative with its rainbow colors, successfully creating a connection between Seonbis and the artist, solidifying the link between past and present.

For Moon Sang Hoon and Azangman, two women artists featured in QueerArch, the research at QueerArch was both eye-opening and painful due to the lack of representation of lesbian artists’ lives in the archive. In the statement for her video piece, Exhibition: Lesbian (2019), Moon writes,

“Why do we have such a small number of queer women artists in the Korean arts community? What made it nearly impossible to be visible?”

“ [...] Despite numerous efforts and attempts by lesbian artists in the past, it seems we can only find their traces through poorly documented photos and oral histories. [...] Have queer female artists failed? But then, what is failure for artists?” As Moon continues her research, she learns more about lesbian artist collectives that were once active such as UnniNetwork, ITDA, and Bozzyparty. After reaching out to some artists from the collectives, Moon re-stages their artworks—several of which had been shown in important historical exhibitions—in a new show (Outhouse, Mangwon-dong, Seoul), and documents them in a video that cross-references content in flyers, magazines, and other publications at QueerArch.

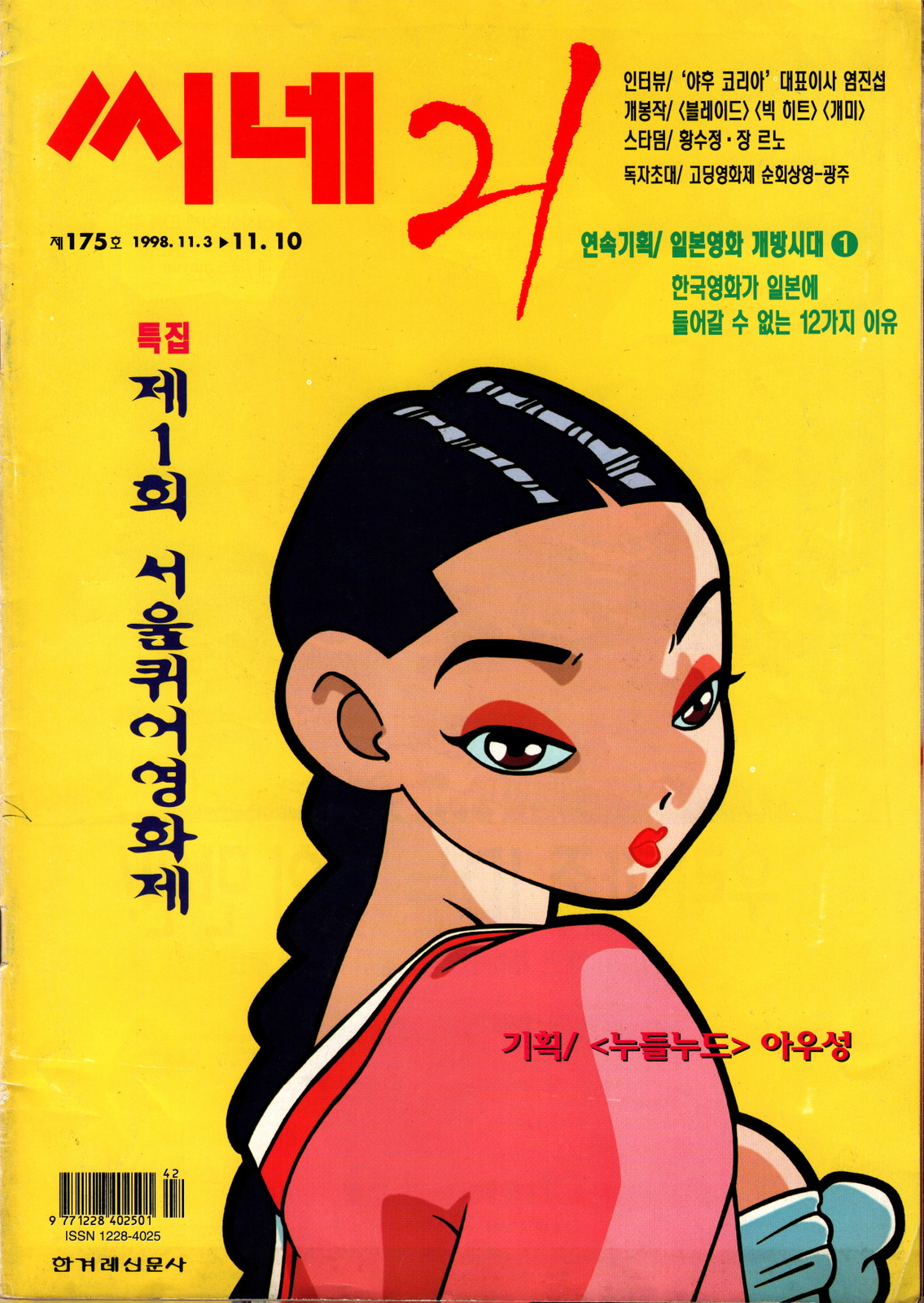

Like Moon, Azangman, a drag king performance artist, wants to dive into the history of drag king performances in Korea, but struggles with the lack of archived documentation. She grapples with magazine advertisements and low-resolution images of the “legendary” performances floating on the internet. Often introduced as one of the first drag king artists in Korea (but knowing there were so many before her), Azangman decides to track down drag kings of former generations and interview them in her work, Touching the Balls of Resurrected Drag Kings (2019). In their collaborative video installation, Moon and Azangman mix and cross-cut their respective videos to create chaos and discontinuity. The disorderly aesthetic of the collaboration suggests that the results of the artists’ research rests somewhere between success and failure, loss and remembrance, but nonetheless remains undoubtedly hopeful.

The history of LGBTQ activism is highlighted in Kyungmin Lee’s work. As co-publisher and graphic designer of FLAG PAPER magazine, he addresses some of the most taboo topics in Korea such as HIV/AIDS and drug abuse in the gay community. What interested Lee the most in the archive were protest signs collected over the past decade. The signs, often with short, strong, clear and witty phrases, are important pieces of evidence alongside recordings of numerous protests concerning equality, LGBTQ rights, anti-discrimination law, homophobia in evangelical Korean churches, and more. In the exhibition, Lee presents a series of acrylic signs with laser-engraved texts selected from the archive.

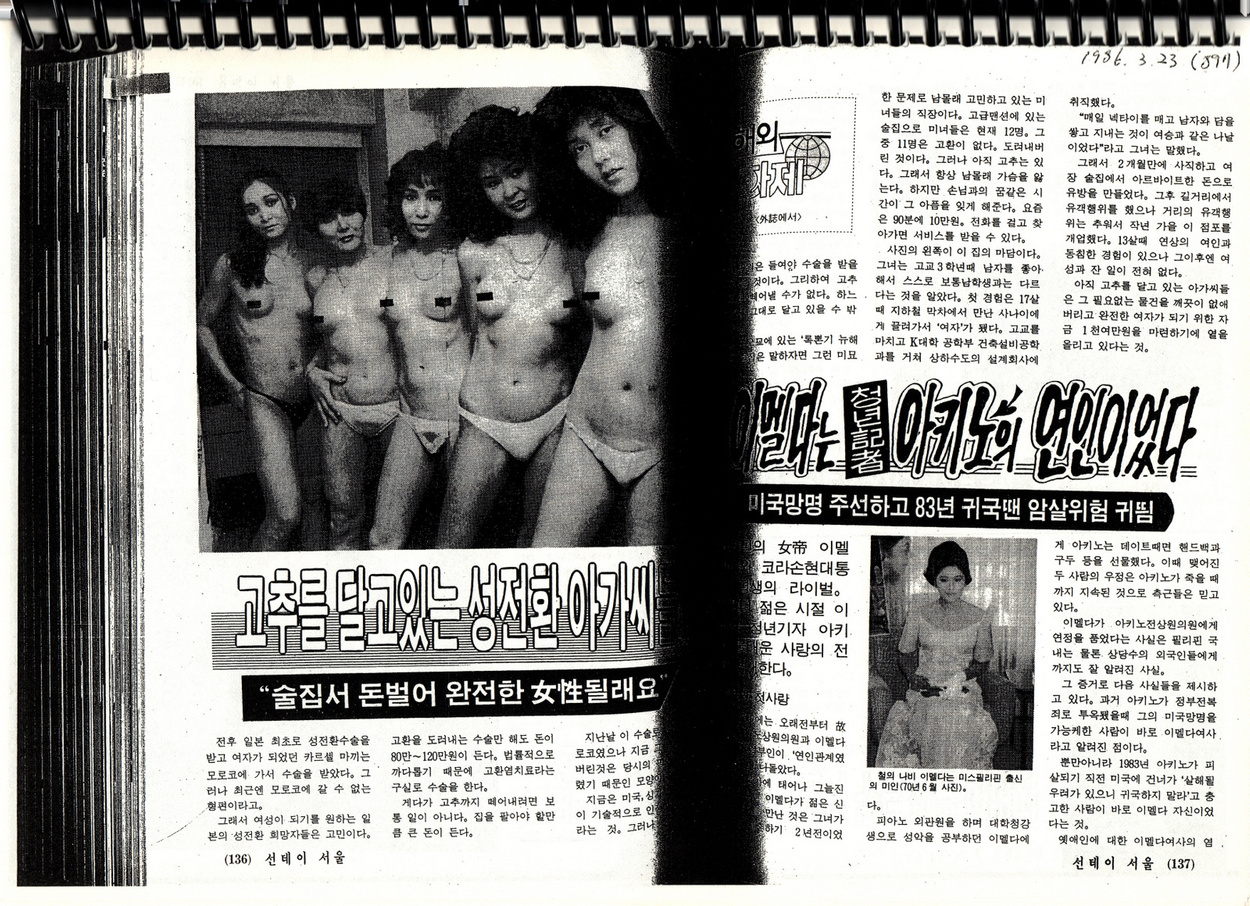

Sehyung Kim, founder and creative director of the fashion label AJO, has been a controversial figure in the Korean fashion industry for a few years. His gender-neutral clothing line AJO pushes the boundaries of traditional sizing and is also known for its mandate to only work with queer and non-professional models. For the exhibition, Kim has designed a sweatshirt—a clothing item chosen for its gender ambiguity—that celebrates the history of transgender lives in Korea. The image printed on the sweatshirt (depicting a group of transgender people at an Itaewon club in the 1970s) was originally published in Prostitution in Korea (1987), a book partially funded by the government.

The book’s original image caption erroneously described the photo’s subjects as cross-dressing male prostitutes.

The misunderstood stories of transgender lives in Korea are made visible in Ruin’s installation. The non-chronological collage of printed images, copies of Japanese colonial era newspaper articles, autobiographies, posters, and moving images were excavated from the archive and pasted together in an effort to to reconstruct the little-known transgender history of Korea. However, the work also underscores the blanks, the absences, the misrepresentation of individuals. Ruin, archivist of QueerArch and transgender researcher in Gender Studies, has been a critical voice in both activism and academia. A strong advocate for the representation of women and transgender people in the archive, Ruin aims to build QueerArch beyond an account of homoerotic male experience.

In April 2019, the artists in this exhibition entered the tiny room of QueerArch looking for something, hoping to connect with traces left by former generations of queer lives, and wanting to establish critical and personal queer histories. The resulting artworks in QueerArch give meaning to not only what is archived but also to what is absent and forgotten.

Through the process of their research and participation in the exhibition, the artists are now placing themselves in the history of QueerArch, which will hopefully be shared and explored by future generations of queers.

As in the case of Harvey—the cactus preserved by Julie Tolentino—what comes across through the works in QueerArch is that the invisible memories of queer lives in Korea are sustained and preserved by the care and the creative potential of different generations of artists, activists, and scholars living inside and outside Korea, coming together through time and space, now and in the future.

Kang Seung Lee and Jin Kwon

Open Call Exhibition

© apexart 2019