In East Asia, the notion of ownership over women's bodies has been stripped away from women themselves. The very concept of womanhood has been imagined and produced to create a social expectation that women should be obedient to their own cultural patriarchy and to privileged Western colonizers. While gender inequality in East Asia is uniquely rooted in the sociocultural histories of each country, the gaze exerted upon women, especially their bodies, remains shared in many ways.

This exhibition features the work of five contemporary women artists who speak out against gender-based discrimination, especially the long-ignored right of East Asian women to own and represent their own bodies. Originally from five different regions of East Asia, each of these artists reflects not only upon her particular cultural context and experience, but also common challenges that women face in this part of the world, where historically, socially and culturally it has been believed that men and Western cultural norms are superior.

There has been a longstanding fight for gender equality around the world. In 2017, the global #MeToo movement awoke a sleeping rage in many women across East Asia, as it exposed injustices that were previously unnamed and endured in silence. The movement spread across mainland China, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, but the overall intensity and impact in these countries was less than in other parts of the world. Local grassroots efforts to call out abuses, such as the indictment of the Japanese journalist Shiori Ito, the allegations of sexual harassment against Chinese TV host Zhu Jun, and Nth Room cases in South Korea received considerable pushback and victim blaming. Resistance to women speaking out came in many forms.

In Korea, an "anti-feminist movement" mobilized in response to the debate triggered by the film Kim Ji-Young, born 1982 which explores the everyday pressures, exploitation, and obstacles experienced by an ordinary Korean mother and housewife. Polls show that 70% of young men in South Korea continue to hold anti-feminist views.1 Japan is ranked 120 out of 156 countries on the Global Gender Gap Report 2021 issued by the World Economic Forum, by far the lowest among G7 countries, while China ranks at 107, and Korea at 102. In Hong Kong, a survey shows that 1 out of 7 women has experienced sexual violence.2 Since the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement began there in 2019, allegations of sexual assault and harrassment of female protesters by Hong Kong police have circulated, and yet there has been no impartial investigation. What has caused this inequality and mistreatment of women in our societies? The goal of this exhibition is to directly address ways in which society's interpretation of the female body negatively affects women's lived experiences, and to show how women use creative practices to refute expectations imposed upon them—reasserting and reclaiming their own bodily agency.

Each artist tackles inaccurate, hyper-sexualized portrayals of women as they are manifested in their respective social contexts and personal experiences. For Kaai Ogaya, "the body of beauty" is a problematic concept imposed by Japanese society. It asserts a societal ideal of the female body that leads women to deny inherent bodily functions, such as the growth of body hair. In The Stars and the Sky, Ogaya transforms black chiffon fabric—a popular material for semi-transparent stockings in Japan that requires women's legs to be hairless—into a piece of sky whose stars are created with flakes of scabs from cuts caused by shaving.

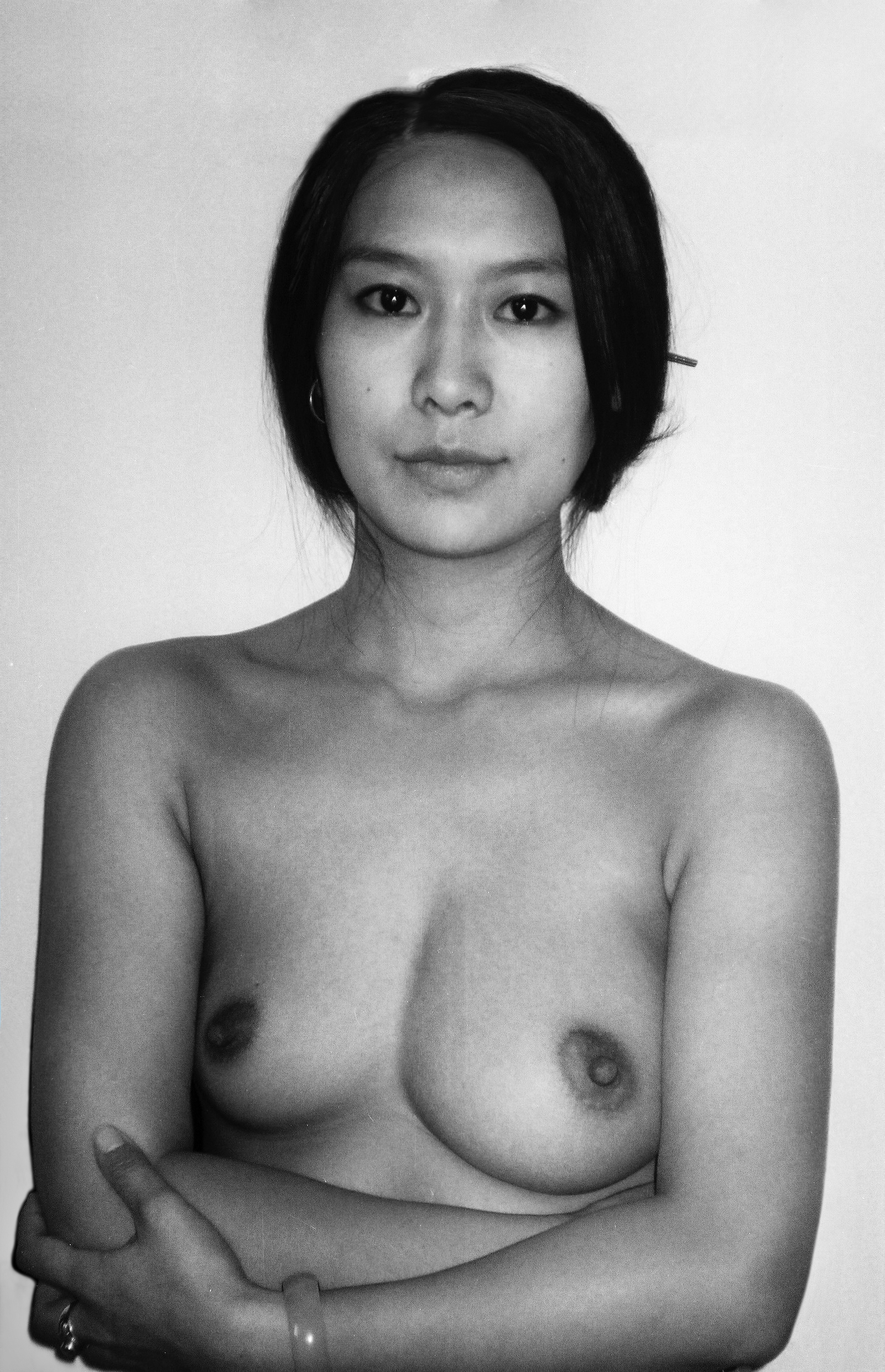

Kaai Ogaya and Dong Jinling both focus on the incongruence between the expectations cast upon the female body and its biological reality. While an adult female body typically has both body hair and is capable of lactation, societal expectations demand that its skin be hairless and its breasts ornamental. Dong and Ogaya critique the double standard that women's bodies are to be adult in practice but prepubescent in form.

After giving birth in 2011, Chinese artist Dong Jinling exaggerated the phenomenon of the so-called "lazy boob." While it is not unusual for those nursing to have uneven milk supply between breasts (resulting in irregularities in size and shape between them), Jinling intentionally used only one breast to nurse her child. The result is a controlled asymmetry that reflects Dong's internal struggle between self-autonomy and the sacrifices necessary to meet the demanding expectations of motherhood in China. In her video piece Dong Jinling 2-2, the artist portrays herself releasing her breast milk into the air, transforming an act of love, utility, nutrition, and bonding into a solo activity of aimless, rhythmic fun.

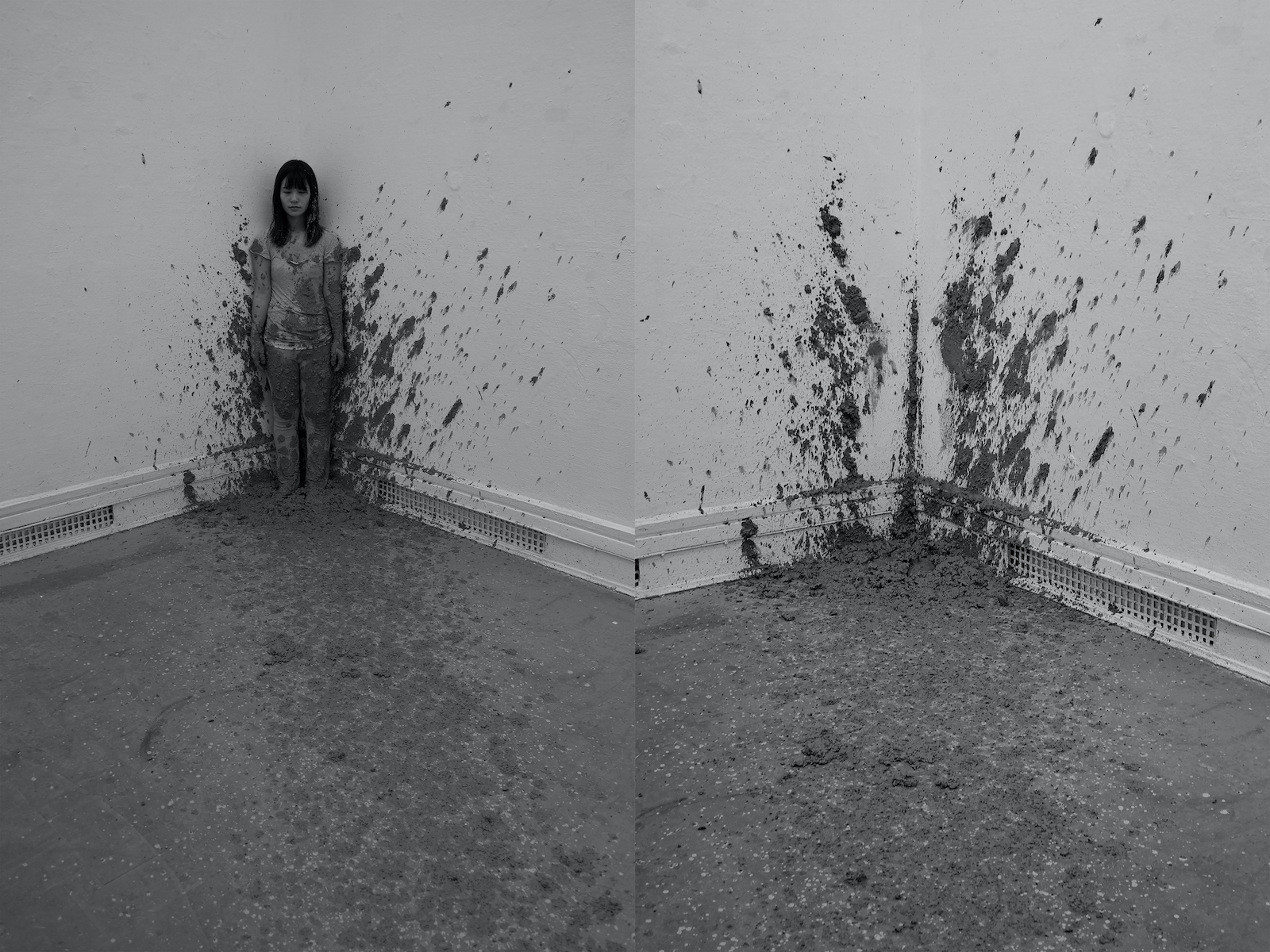

Nayoung Jeong and Wong Ka Ying explore the relationship between colonial capitalism and women's bodies. Nayoung Jeong, a native of South Korea who has lived overseas for many years, finds herself innately aware of the Western gaze and its implicit expectations of Korean women. Her performance piece Catch or Throw translates her experience of navigating the assumptions cast at her in the Western contexts of the United States and the United Kingdom. In it, the artist attempts to catch handfuls of mud which are thrown at her, mud which aims to mark her as an exoticized Other. Despite her efforts, the mud eventually covers the artist, smothering her own body and true identity. The residue of the performance leaves an outline of the artist, an anonymous portrait in negative. A performance of the work will take place as part of the exhibition's programming, along with documentation.

Wong Ka Ying, who is based in Hong Kong, works with the ubiquitous cultural trope of fortune cookies to draw attention to the commodification of women's bodies in East Asia. Fortune cookies have long functioned as a symbol of East Asia since they are sold in Chinese restaurants and often contain a Chinese phrase; however, their assumed origin is just a fictional marketing strategy. Evolving from a Japanese "fortune cracker," the first fortune cookies were produced in California and to this day are largely produced in American factories.3 Ka Ying draws comparisons between the fictitious, exoticized associations and marketing of fortune cookies and Asian women. While both are sold based on the appeal of their individuality, they are also traded as products of mass consumption in a capitalist system—mythologized as a means to fulfill the consumer's exaggerated and stereotyped expectations of East Asia. In her work, Ain't No Your Fortune—an installation comprising an oversized box of paper fortune cookies, video, and printed images—Wong questions the ways that the female body is fetishized and treated as a product for consumption.

Tying together the exhibition are three video works from the Taiwanese artist Betty Apple's performance series Vibrator Love of Sound. The works consist of musical arrangements made with eclectic instruments ranging from vibrators to wigs to shopping trolleys. Unencumbered by the canonized conventions of "good" music, which have been heavily shaped by colonialism and the subsequent cultural influence of the West, Betty Apple's "bad" noisic performances are fun, chaotic and bold. The result is an unmistakably feminine, rebellious chaos as the body converses with the object and subverts female passivity into an empowering discovery. Vibrator Love of Sound is an ongoing performance series since 2012 that has traveled to many cities in the world. The three performances selected for this exhibition are: #02 in Taipei (2012), #06 in Berlin (2014) and #14 in Bergen (2019), outlining the development of the artist's style over time.

Though many of the works on view exude an irreverent exterior—whether creating quaint starry scenes, making fountains of breastmilk, throwing mud, presenting cartoonishly large fortune cookies, and singing into vibrators— these playful and sarcastic depictions of the female body conceal (and more importantly help make possible) a biting criticism of the paternalism and reverence for Western norms that still permeate many aspects of societies throughout East Asia.

Women across the region are refusing to remain complacent to longstanding systems that exercise control over our bodies, that perpetuate sexualized stereotypes, and that restrict who we can be and what we can do. It is our hope and expectation that through a shift in culture, made possible through increased dialogue and creative expressions, we can help reshape collective consciousness about gender equality in our region.

Mizuho Yamazaki and Virginia Liu

Open Call Exhibition

© apexart 2022

1. Jake Kwon, "South Korea's young men are fighting against feminism," CNN Online, 24 September 2019, accessed 3 May 2021, https://edition.cnn.com/2019/09/21/asia/korea-angry-young-men-intl-hnk/index.html.

2. Hong Kong Women's Coalition on Equal Opportunities, A Survey on Hong Kong Women's Experience of Sexual Violence 2013, May 2013, accessed 3 May 2021, https://rainlily.org.hk/publication/wesv13.

3. Michael Lee, "The Surpring Origins of the Fortune Cookie," History.com, 11 Feb 2021, Accessed 20 Oct. 2021, https://www.history.com/news/fortune-cookies-invented-chinese-japanese.