Gender-based violence is distressingly commonplace in Nigeria, disproportionately affecting women and girls. It is a phenomenon that is unfortunately also endemic in many societies across the globe. Worldwide, it is estimated that one in three women experience physical or sexual abuse in their lifetime,1 yet in many parts of the world it remains shrouded in a culture of silence. In a bid to confront such suppressive norms, Arewa, Me Too is an exhibition that examines the mainstream portrayal of women in Northern Nigeria: confronting social stereotypes and normalized acts of violence, and their impact on the women who live in this region.

Combining the local term for northern Nigeria (Arewa), and the global hashtag-turned-social-movement against sexual harassment and violence (#MeToo), Arewa, Me Too brings the critique and energy of the movement to Kaduna, empowering its residents to stand up for womens' equality.

In a highly religious and patriarchal society like ours, where religious beliefs, norms, and social institutions are held in high regard, violence against women is rampant. Ranging from domestic violence, sexual harassment, rape, female genital mutilation, and child marriage amongst others, gender-based violence undermines the health, dignity, security, and autonomy of its victims.2 In addition, the ongoing terrorist insurgency across the country, led by Boko Haram, has contributed to the rise of violence against women. Women are regularly abducted, and have been used as instruments of war in forced suicide bombings. In April 2014, over 270 schoolgirls were kidnapped by insurgents at an all-girls boarding school in Chibok. About 100 were released following negotiations, and while some others managed to escape, many did not. Reportedly, a 70-year-old man raped a 3-year-old girl. More recently, a six-year-old girl was raped to death by unknown men in Mararaban Jos, Igabi Local Government Area of Kaduna state. This form of violence targeted at girls and women is traumatizing, and instills fear in its victims, making it difficult for them to speak up and consequently rendering them vulnerable to stigmatization.

Through the works of women artists living and working in northern Nigeria, Arewa, Me Too sheds light upon gender-based violence, the silence around which contributes to a culture where women are not afforded the same rights, privileges, and safety as men.

Martha Panshak Dasat's photography series Endangered Gender is an examination of gender- based violence (including forced marriage and child marriage), its intersection with culture, and its physical and psychological effects. Through her black and white photographs, the artist presents various ways women have been subjected to reductive socio-cultural standards. The striking monochromatic images render the subjects simultaneously familiar and unfamiliar: this is the artist's way of holding the viewer's attention, away from distractions in the background.

In many ways, women have been conditioned for societal gender roles and stereotypes through their indoctrination since childhood, which later reinforces implicit beliefs. According to Martha, women are strongly influenced by their social context, which asserts that being a "good" woman means living a modest life: being submissive in order to get married to a "good" person, raising children, and caring for the family. These conditions secure honor for the woman and her family, yet they also make women vulnerable and dependent, and they perpetuate violence against women and girls. The artist explains, "It is important that girls begin to see themselves differently, free from boundaries that limit their freedom. We must begin to shape how they see themselves. I realized that many of them don't know. As such — as a woman, a mother, and an artist — I have to highlight these topic issues in black and white." Accompanying the series is a photo booth with a self-timer camera where participants are encouraged to look directly at the camera, and take a self portrait. The printed photographs are mounted in solidarity with the fight against gender-based violence.

Maryam Umar Maigida's series of paintings titled In the Absence of Humanity challenges stereotypes about women, especially regarding notions that certain trades are for men only. She confronts social conditions that have brainwashed generations of women to believe that they are lesser than their male counterparts. While acknowledging these issues, Maryam draws attention to women throughout history who have demonstrated that traits of leadership and intellectualism are not limited to men. Maryam depicts northern women like Queen Amina of Zazzau, a legendary 16th century ruler who oversaw war-driven territorial expansions and exercised ingenuity in establishing architectural defenses; the poet, scholar, and activist Nana Asma'u (sister of Sultan Usman Dan Fodio) who was at the heart of a movement promoting women's literacy and agency across the north in the 19th century Sokoto Caliphate; and more recently, the post-independence activism of Hajia Gambo Sawaba — who was outspoken against child marriages, amongst other things — in the mid to late 20th century, and who remains an inspiring beacon of equity and justice.

Halima Abubakar's series Patterns revises the perception of the role and contributions of women in society. Drawing references from her experiences, she stitches scenes from her life as a projection of what women go through while navigating selfhood, and societal expectations of womanhood. In a society like ours, women are believed to be more nurturing than men. As such, the traditional view of a woman's role prescribes that she should nurture her family by working at all hours within the home, rather than taking employment outside the home. While highlighting the negative impact of these expectations on women's self-perception, Halima draws attention to the emotional trauma generated in the process, and presents new ways of re-writing and re-imagining oneself. She observes that, "changing the way we see ourselves influences the way the society sees us."

Taking the viewers on an emotive journey, in expressionistic and diaristic styles, Halima uses colors as a locus for exploration to highlight subliminal influences and complexities of womanhood. She presents performance documentation via images titled Red Herring, White Lies, Out of the Blues, Antithesis, Providence, and Vestiges, which tell varied stories of uncertainty, hurt, love, anxiety, and calmness. In these documentation images, the artist is wrapped in fabrics bearing red, blue, white, purple, green, and coral colors to explore the relationship between pigment and emotion, and the role of fabric in identity making.

Through her works, Halima establishes a safe space where women embrace the experiences that come with every stage of their lives; a place where they can be whoever they want to be, and can be appreciated as such without discrimination. She hopes that women who have been struggling with self acceptance and low self-esteem will find healing, and courage to re-establish or re-make their own identities.

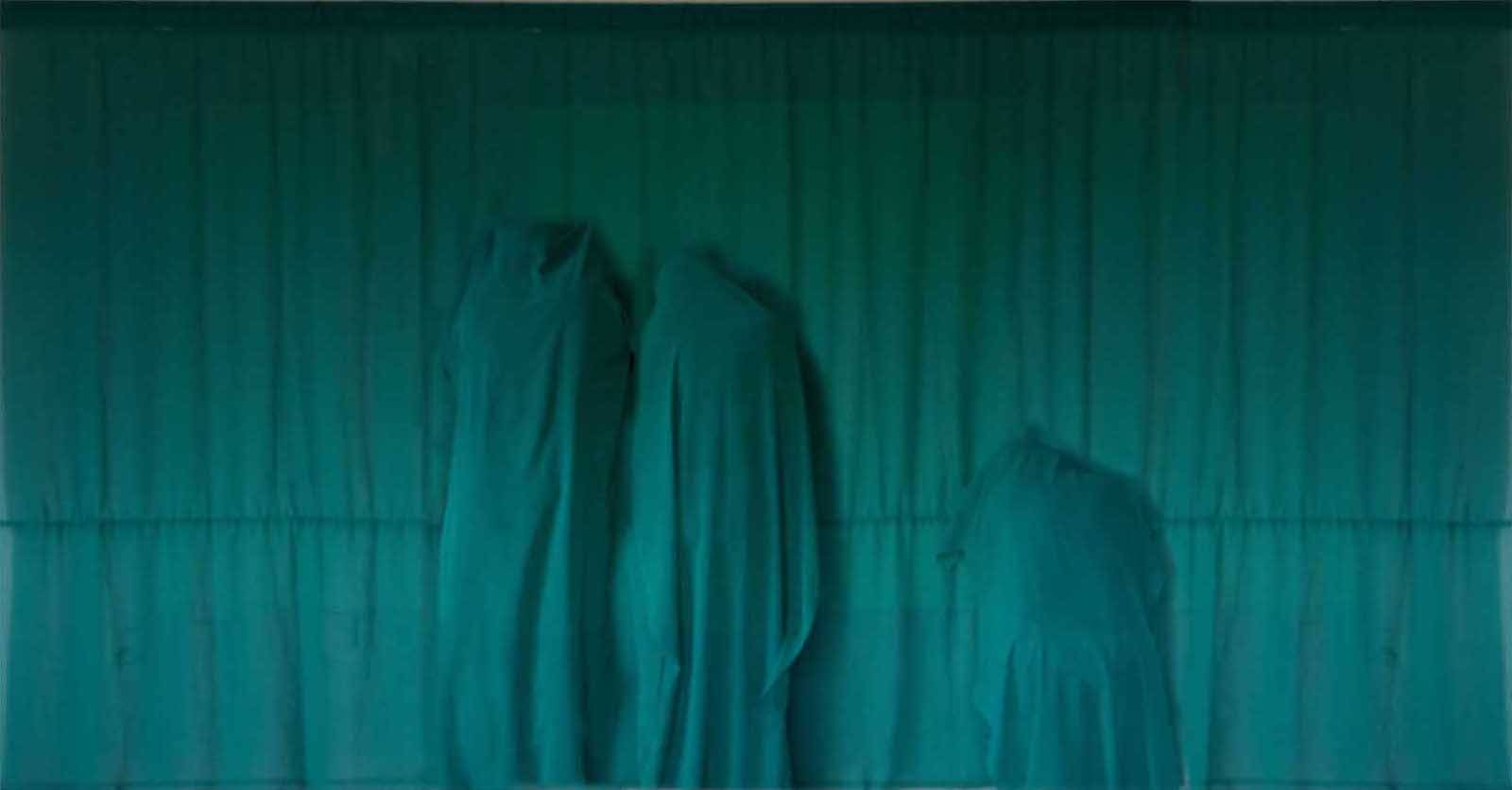

Judith Daduut's The Covering series, Pulsating Silence series, and Reflective Healing series are all intimate reflections on traditional and traumatic experiences of women, silence, resistance, acceptance, and healing.

The Covering series depicts how women have been restrained in our contemporary society. The subjects of Judith's photographs are concealed female identities. The installation of these images on each side of the exhibition's entrance, and exit, serve to strategically welcome viewers into a thought provoking dialogue and make them leave with sobering thoughts.

In Pulsating Silence, she metaphorically shows a progression — from restrictions to resistance — of how women have been controlled. The artist does this by depicting her female subject with her mouth and face shrouded with gauze, and later in the series shows the subject defiantly removing the gauze.

Reflective Healing explores the juxtaposition of words and images as a powerful tool of recovery for victims of gender-based violence. Quoting the 16th president of the United States, Abraham Lincoln, in her photographs, as well as other words of affirmation, Judith highlights the process of healing as a collective effort.

Accompanying the exhibition is a short film Rufe Kai (Cover Up), a unique exploration of the perceived relationship between bodies and textiles. The film's narrative counters assumptions that victims' clothing choices correlate with a likelihood of assault. Additionally, a section of the exhibition called "Seventh Haven" is dedicated to survivors of sexual violence: inviting them imagine what constitutes a safe space, using permanent markers to write, draw, paint, and sketch on the wall.

Arewa, Me Too is an invitation into a safe space where support systems are encouraged, and healing is visible. Each artist presents an opportunity to examine the mainstream portrayal of gender-based violence, confronting stereotypes and abuses, and inspiring conversations on women's liberation within a conservative society.

Favour Ritaro

Open Call Exhibition

© apexart 2022

1. United Nations, Gender-Based Violence Against Women: Decade of Action, 2020, accessed 15 December 2021, https://tinyurl.com/2mncybwm.

2. United Nations Population Fund, Gender Based Violence, 2017, accessed 15 December 2021, https://tinyurl.com/3sdj3mes.