Early in the life of the Tribeca Film Festival, I interviewed the then director of the festival for our upcoming coverage in The Tribeca Trib. Here and there she would mention Tribeca. Tribeca this, Tribeca that. Tribeca, Tribeca, Tribeca. “Wait,” I asked naively. “Are you talking about Tribeca, the film festival, or Tribeca, the neighborhood?” It seemed not to have occurred to her that she’d merged the two. Tribeca no longer was the place of the annual event. It was the event. The brand. I shouldn’t have been surprised. Nearly a decade before, Tribeca was already becoming a global brand. Most everything from racehorses and rap artists to bars, bracelets and yachts were adopting the name. The Trib’s computer search back in 1998 found the neighborhood described as “trendy” in more than 1,000 restaurant reviews, gossip columns and news stories. Imagine what those numbers would be today.

“It has an ultra-cool, hip and happening feel to it,” said a Los Angeles designer about his new necklace, the Tribeca. The name “resonates with the international community,” concurred a Belfast developer after announcing last year that “Tribeca” would be the name of a large redevelopment project in a neighborhood known as Cathedral Quarter. Opponents blasted the idea (#WeKnowWhoWeAre) and one even presented his argument before the City Council in verse. “We are not Tribeca!” he intoned dramatically. “The name will not last/We are CQ, Cathedral Quarter/The historic heart of Belfast!” Given the real Tribeca’s over-hyped reputation for trendiness, wealth and celebrity, do #WeKnowWhoWeAre? The Tribeca Show does not try to define the neighborhood. Rather, it seeks to de-brand it.

Through the perspectives of five long-time Tribeca-based photographers and one local poet, the show provides diverse and divergent views of the neighborhood across the decades, defying the insistent media focus on glitz and glamour. Photographer Donna Ferrato brings a quirky and sardonic eye to a body of work on the neighborhood’s street life that has resulted in two books. Her affection for the area always sides with grit over glamour. Nearly every image seems an unexpected one for Tribeca: a beach-like scene on Church Street, a solitary woman on a dark and otherwise empty Leonard Street, a menacing figure—even for Halloween—on Jay Street.

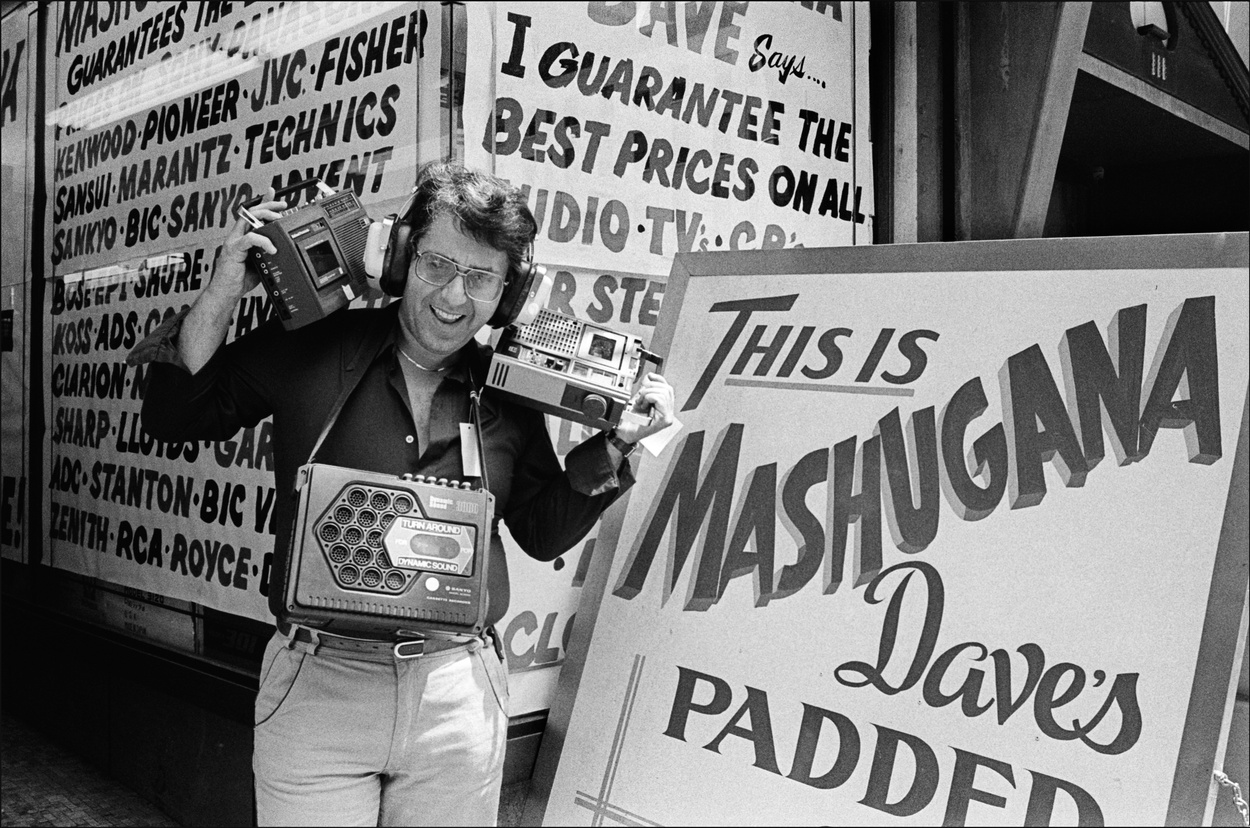

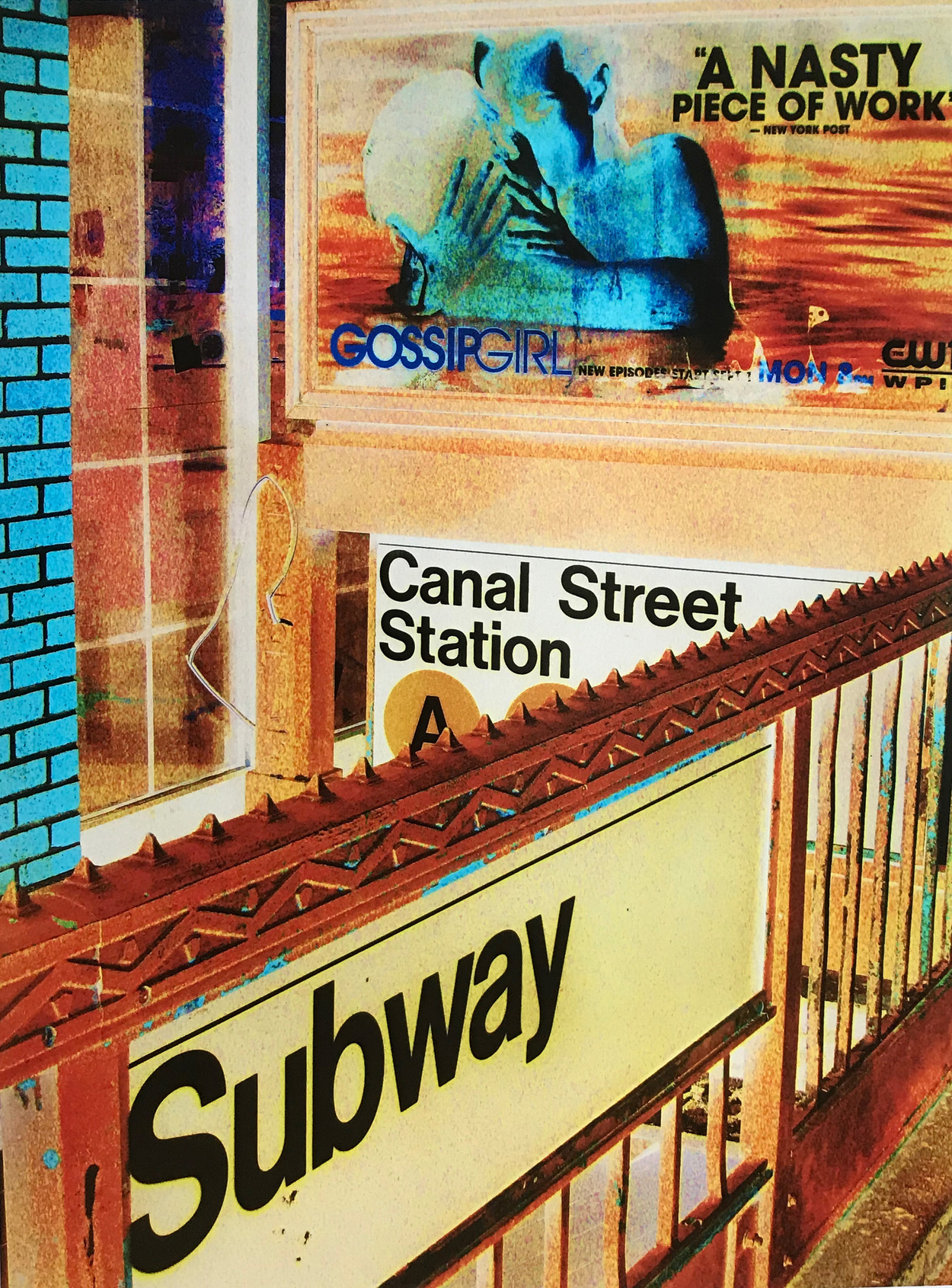

Susan Rosenberg Jones’s Building 1 presents portraits, both intense and empathetic, of longtime residents in Tribeca’s formerly middle-income high rise development, Independence Plaza. Her subjects and their living spaces veer far from the common idea of the Tribeca lifestyle. Their homey apartments, often crowded with possessions acquired over a lifetime, are in stark contrast to the neighborhood’s airy lofts. Allan Tannenbaum, who moved into the raw space of his Duane Street loft 45 years ago, provides a rare and humorous view of Tribeca’s plebeian commerce of the 1970s. “Bargain” stores with names like Dr. Schlock’s and Mashugana Dave’s scream out to passersby, “Last Call!” “New Items Daily” and “Best Prices.” That’s hardly the look of today’s Tribeca, though here and there, on Broadway and Canal Street, their distant cousins survive.

Another Tribeca pioneer, Marc Kaczmarek, settled in his Walker Street loft in 1974. Through the use of tone manipulation, he shows the neighborhood in fresh and unfamiliar ways, giving a lustrous beauty to the area’s muted streetscape and challenging the way we see the everyday. Max Blagg’s contribution takes the form of a commissioned poem dedicated to the neighborhood. As a poet who has lived in Tribeca for over 40 years, Blagg has developed an annual tradition of honoring the winter solstice with writing a new poem. Each year he hangs copies of the poem from a clothesline that he strings between trees in Tribeca Park: an offering to neighbors and passersby, much like the poem that he hangs in apexart’s gallery for this exhibition.

And then there are the show’s archival photos, reminders of the din of different times, like the clatter of wagon wheels on cobblestone streets or the deafening roar of the el above. Such images, so far from the neighborhood we now know, nevertheless recall the area’s evolving past as visual context to the Tribeca of today. As a photographer I have been chronicling the neighborhood in The Tribeca Trib for the past 25 years. When April Koral and I launched the paper in September 1994, we couldn’t have foreseen that the neighborhood was on the cusp of a new era and a freshly refinished reputation. Although already largely residential, many warehouses and other industrial buildings still dotted the landscape, yet to be turned into today’s palace-priced lofts. Pigeons resided where the rich and powerful now live. Our first major stories chronicled the public review—and often heated debate—that accompanied rezoning proposals to allow, “as of right,” new retail and residential conversions of the old buildings and accelerated new apartment construction.

With the social and economic landscape changing around us, and the burgeoning family population that came with it, The Trib’s stories and photos remained focused on the unglamorous yet vital life of the community. The photographs here convey a wide-ranging sample of what makes up an ill-defined sense of place—from the last day of a local coffee shop to a summer evening of dancing on a Hudson River Pier, and many moments in between. Hardly momentous, but meaningful to our readers. Often, those stories have highlighted the residents truly deserving of boldface attention. Step into any local park—Washington Market Park, Duane Park, Tribeca Park, Canal Park, Finn Square, or Bogardus Garden (now under major reconstruction). Play minigolf or volleyball on Pier 25. Take a free kayak ride from the Downtown Boathouse or go on an Art & Culture Night tour of local galleries. One way or another, each came about thanks to a few dedicated local volunteers who took it upon themselves to help elevate the neighborhood into a community. Dedicated volunteers, too, did the painstaking historical research on neighborhood buildings that led to the city’s landmarking—saving, really—of large swaths of the 19th century industrial landscape that architecturally defines the neighborhood.

It was that preservation that certainly helped turn the area into one of the country’s richest zip codes. As Forbes gushed last year, Tribeca “boasts one of the world’s largest collections of Neo-Grec designs and wrought-iron facades, in loft-style low-rises that real estate investors from around the globe covet.” For all its presumed panache, and despite its Carters, Swifts and Timberlakes, Tribeca remains in many ways the same small town-in-a-big-city kind of place that in 1994 felt like the perfect place to start a local paper. Newsweek may headline “The 7 Best Places to Spot A Celebrity In Tribeca,” as it did last April, promising readers that they might bump grocery carts with Meg Ryan at Whole Foods. And yes, big money is part of Tribeca, as are the celebrity sightings, weeklong film festival hubbub and the rest. But is that all we are? The Tribeca Show means to say no. Like any famous location, there is a reality behind the legend. The artists in the show remind us that a broad spectrum of life is missing from the area’s reputation. It is through their eyes, and through their decades in the neighborhood, that we can come closer to seeing the true community called Tribeca.

Carl Glassman and April Koral

Open Call Exhibition

© apexart 2019