In our increasingly digital world, tech failures seem to pop up all the time and just when we least expect them: an app suddenly crashes, a screen cracks, a video glitches, an ATM displays an out of order message, a text message never goes through, or that spinning wheel of death won't stop twirling. Indeed, we often take technology so much for granted that we only really notice it in the moments when it breaks down.

As technology becomes more sophisticated, and also more embedded in our political, economic, and legal systems, seemingly small errors can result in huge consequences: a distorted data set prompts an extended jail sentence, a hacked voting machine sways an election, a poorly-inspected flight navigation system results in a plane crash, a biased algorithm rejects a job application, an imperfect facial recognition scanner misidentifies someone at a border checkpoint. In cases from the mundane to the momentous, failure frequently signifies that something deeper in the system has gone wrong.

SYSTEM FAILURE is a fatal error notification, an invitation to examine the systemic injustices in built technologies, and a warning that we must personallyy scrutinize the idea of failure itself if we want to be productive creators and citizens. Presented in San Francisco, a hub of technology and diverse artistic and social movements, this exhibition explores intersections of failure and technology through creative practice in three interconnected nodes.

First, in the ideologies of success fostered within start-up culture—fail fast! fail big! fail often! fail better!—and how industry jargon like iterating, pivoting, and innovating uncritically leaks into everyday discourse and civic institutions in the Bay Area and beyond. Second, through the ways in which technology actually fails and fails us, particularly those moments of breakdown that both reflect and shape inequities and injustices already present in our world. And third, in rejecting success altogether by designing tools, techniques, and tactics that were never meant to function properly, thus reveling in the joys of living outside the expected norm.

As any programmer knows, quite often failure isn't a bug, but a feature of a technology. That is, while genuine mistakes do get made, the biggest problems are often those that are built right into the system, due to faulty methods, short-sighted variables, or unreasonable arguments. By focusing on failure, this show aims not to point fingers or dwell in defeat, but instead to build accountability for the systemic errors that occur at all levels of our sociotechnical stack.

Failure is central to any creative or learning process, as often the best insights are borne out of accidents and an ability to refine an idea over time. But Silicon Valley's culture of disruption intensifies this drive toward imperfection, reifying approaches to creativity into corporate slogans like Facebook's infamous motto “move fast and break things.” In a tech economy of seemingly endless venture capital, this high-octane risk taking earns creators points and funding for taking the biggest and boldest step, even if that takes them right off a cliff. But in an industry and society already built on an uneven playing field, we ask: who really gets to fail? And who bears the consequences of an economy and culture that is constantly reinventing itself and can't sustain its own successes?

In this vein, Jenny Odell and Joe Veix's wry digital collages take Silicon Valley culture head-on, compiling graphics found in publicly-available slide decks of failed startups, playfully poking fun at technologists' attempts to change the world through corporate pitches.

Stephanie Syjuco's Spectral City (A Trip Down Market Street 1906/2018) reimagines the Miles Brothers' early film, shot traveling down San Francisco's central business corridor just before the Great Earthquake, through the present-day virtual gaze of Google Earth. Devoid of humans but full of glitchy digital artifacts, Syjuco's video brings into sharp focus a ruptured urban geography that is coming apart due to the influx of tech dollars and the displacement of long-term residents.

In recent years, tech has produced some high-profile blunders: artificial intelligence (AI) assistants that can't parse speakers' accents, real names policies that unfairly impact queer and trans people, algorithms that incorrectly identify dark-skinned faces, corporate leadership and engineering teams made up predominantly of white men, and major breaches of user data and privacy, to cite only a handful. As a number of researchers have recently demonstrated, such as Saufiya Umoji Noble's Algorithms of Oppression, Virginia Eubanks's Automating Inequality, and participating artist Mimi Onuoha's “Notes on Algorithmic Violence,” up-and-coming technologies like AI, big data, and machine learning often hard-code inequities into platforms by using biased data, incorporating racist and sexist cultural assumptions, and excluding diverse developers and users at all stages of production. Indeed, often relying on technology as a problem-solver, or giving it too much credit as a tool for social change, can be flawed premises in the context of big tech's “there's an app for that” ethos. As critics like Zeynep Tufekci and Evgeny Morozov have argued, tech's ideology of “solutionism” offers a technocratic belief that complex social, political, and economic issues can be solved by technology itself rather than through public debate or collective action.

Engaging directly with these micro- and macro-level failures are artists like Mimi Onuoha, whose work Us, Aggregated uses reverse image searches to understand how machines “see” and categorize us. Onuoha uploads personal family photographs to Google's Search by Image feature, effectively highlighting the dubious assumptions at play when technologies algorithmically classify visual similarities and differences that are more complicated to a human eye. Similarly, Caroline Sinders asks “what is feminist data?” Bringing a pedagogy of praxis directly into the gallery, her Feminist Data Set invites us to scrutinize the very training data that algorithms are built on, and to contribute to a corpus of information that will ultimately be used to build a more equitable AI system.

In the interactive chatbot Sandy Speaks, American Artist creates a living memorial to Sandra Bland, a young African American woman whose 2015 arrest for a minor traffic violation and tragic death by hanging in Texas sparked national outrage. As viewers ask questions of a fictionalized Bland (whose responses are based on Bland's own social media posts), the piece indicts not only the deep injustices of policing and prisons, but also the limitations of corrective measures like body cams to capture the whole truth, as well as of witnessing and responding to racialized violence via social media.

In a more playful register, Tega Brain and Surya Mattu's Unfit Bits critique the compulsion to track all aspects of our behavior and movement, which provides employers and large corporations with the means to constantly surveil our health and whereabouts. By offering DIY techniques to fool fitness trackers with dummy data, this speculative piece acknowledges both the nefarious and ubiquitous uses of surveillance and how technologies can be outsmarted by taking advantage of obvious loopholes in their design.

In Sharp Tongue, Xandra Ibarra creates an indecipherable code for encrypting gossip, leaving only a graphic notation of sentence structures and symbols that blackboxes their meaning. In a digital culture in which we are constantly hailed to publicly post personal information, Ibarra's work establishes an archive of opaque thoughts and feelings that refuses to be made transparent or subjected to communal scrutiny. Finally, in nahasdzáán bi'th ha'ní, Demian DinéYazhi' gestures towards settler colonialism's extractive relationship between technology and the environment, ultimately offering a meditation for healing played on an iPhone that can only be heard by the land in which it resides.

Many artists, activists, and theorists similarly propose tactically employing forms of failure not only to proactively avoid the harms of technology, but also to create new ways of living outside of normative ideas of success rooted in white supremacist, capitalist, ableist cis-hetero-patriarchy (to paraphrase bell hooks). For example, in books like The Queer Art of Failure and The Undercommons, Jack Halberstam, Fred Moten, and Stefano Harney propose choosing to engage modes of noncompliance, refusal to participate, ignorance, and illegibility as ways of weaponizing failure to thwart surveillance or co-optation by dominant culture. Such techniques, which include common technical approaches like hacking, obfuscation, and pushing systems into overdrive, may be short-term, impractical, or otherwise fail to work, but all help redefine the metrics of mainstream success while calling out games that are already unwinnable because they're stacked against us.

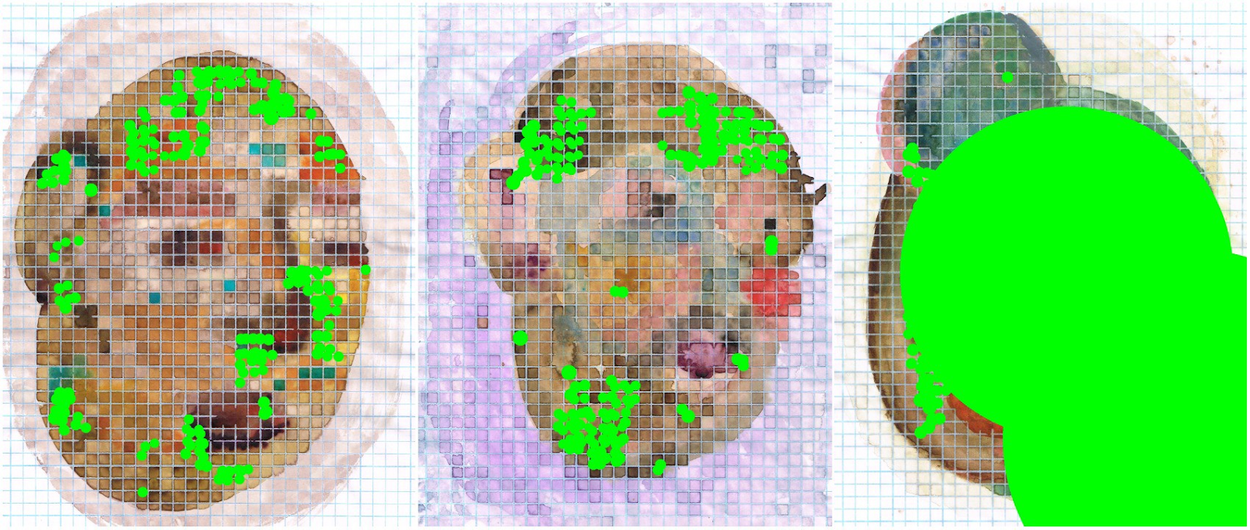

Along these lines, Faith Holland's Queer Connections riffs on the gendered and sexualized nature of “male” and “female” cords and connectors, inventing erotic pleasures of technologically incompatible pairings. Similarly, Robbie Barrat's AI-generated nude portraits display an uncanny quality, gesturing towards the limits of computers truly learning how to paint the nuances of the human form (as well as the limits of an art historical canon that favors certain types of nude bodies), while acknowledging the chaotic beauty of their attempts. M Eifler aka BlinkPopShift also uses AI but in a completely novel way; watercolor portraits are fed through a facial recognition neural net, but return only low confidence scores, pock marking the portraits with bright green loci of failure.

Ultimately, SYSTEM FAILURE suggests that critically examining the forms of failure is key to understanding technology's impact on our lives. Sometimes it's a failure to launch, to land, or to take root. At other times it's a failure to hide, to see, to comply, or to surrender. Or even to adequately bend or break. And too often, failure is exemplified in an inability to perceive the smallest of details and an unwillingness to envision the bigger picture.

If we are truly to make good on the repeated promises to “do better” in tech and society, we must not only learn from past mistakes but prevent future errors. We must audit our collective data, networks, and algorithms at every level, taking care that our actions do not negatively impact our most marginalized neighbors. We must redefine success for ourselves, while ensuring that it doesn't come at the expense of someone else. And we must create safe spaces in which being imperfect is part of a process of learning and growth that is available to anyone, not just those who are deemed too big or too powerful to fail.

Harris Kornstein and Cara Rose DeFabio

Open Call Exhibition

© apexart 2019