"Sometimes, I feel discriminated against, but it does not make me angry. It merely astonishes me. How can anyone deny themselves the pleasure of my company? It’s beyond me."

— Zora Neale Hurston (1891–1960)

CBGB’s, New York City, 1996. It was the first time I had ever watched the force that was Wesley Willis—the unclassifiable outsider cult musician—perform: shouting, singing, rhapsodizing. After the show, I went next door and bought one of the remarkable pen-and-marker Chicago cityscape drawings that had become his artistic calling card, and in exchange, Willis offered me a headbutt, his friendly salutation, making for an unforgettable transaction on the Bowery. Around that same time, as my eyes slowly started to open to art thriving in unexpected places, I would often see striking pieces woven into the fabric of the street itself; along Astor Place, a series of bright orange, purple and green birds of paradise threaded through chain link fences, with red ribbon pulling together the geometry. This, as I came to learn, was the handiwork—frayed, weathered, flapping in the breeze—of Curtis Cuffie, who had developed a complex language of assemblage sculpture during many years of homelessness.

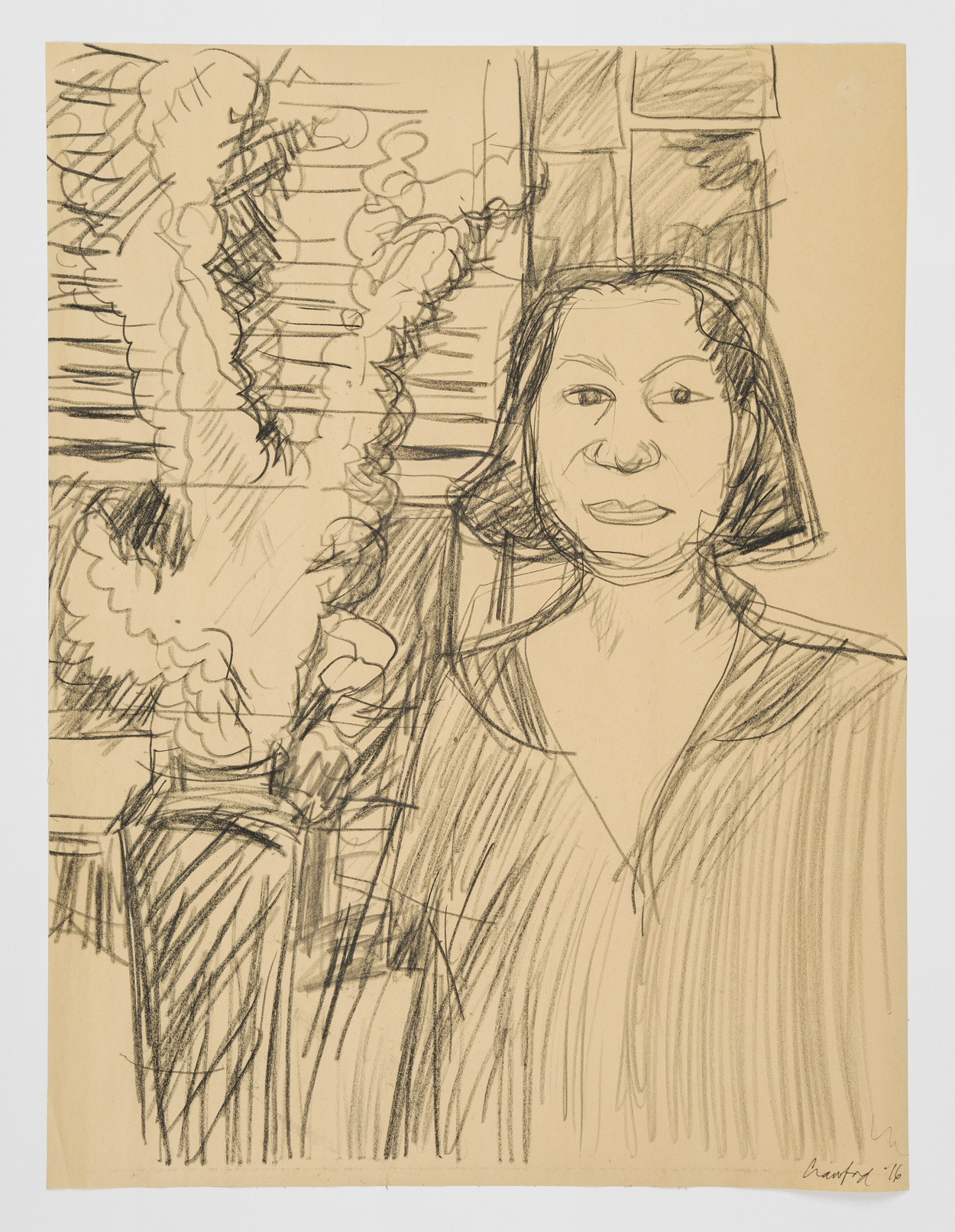

In 2017, I co-founded the gallery Gordon Robichaux and started working directly with the African-American “outsider” artists Frederick Weston and Otis Houston Jr. In our curatorial projects and exhibitions at the gallery, other under-recognized African-American artists began to come to our attention—designer Sara Penn, for example, and singer-artist Stephanie Crawford—sparking memories of Willis and Cuffie, those artists whose work had so radically reoriented my thinking in the ’90s.

A year before opening the gallery, while working with the organization Visual AIDS on an exhibition, I had met Raynes Birkbeck, whose fantastic drawings and sculptures also made a lasting impression on me. In my research and work, I came upon other artists like him who fell into a common racial-geographic grouping: Alvin Baltrop, whose mother, Dorothy Mae, gave birth to him in the Bronx in 1948 after moving there from Virginia; Joyce McDonald, whose parents Willie (Baby Boy) and Florence (Black Gal) McDonald, always known by their nicknames, came North from Alabama in 1949 after the war to raise their family in Brooklyn’s Farragut Houses, where she was raised with her six siblings and still resides today; Bruce Davenport, Jr., who changed his name to Dapper Bruce Lafitte, in honor of the Lafitte Housing Development in the 6th Ward of New Orleans, where he grew up and which was demolished post-Katrina.

I came to perceive a larger historical context for all of these dynamic artists, a pattern that could be traced to the Great Migration—the movement of six million African-Americans from the rural South to the urban Northeast, Midwest, and West between 1916 and 1970.

Souls Grown Diaspora on view here at apexart is the culmination of my thinking about this phenomenon and all my looking over the years at its effects—a project that I hope will help bring into focus a generation of visionary contemporary African-American artists from throughout the United States, and situate their work amid the broader cultural lineage of the Great Migration.

The show’s title takes its inspiration from Atlanta’s Souls Grown Deep Foundation, which has worked for decades to change the canon of art history to include a group of pioneering African-American artists from the South—among them Thornton Dial, Lonnie Holley, Mary T. Smith, Hawkins Bolden, and the women’s collective known as the Gee’s Bend Quilters (Arlonzia Pettway, Annie Mae Young and Mary Lee Bendolph)—as essential to understanding various developments in the history of American art. The name “Souls Grown Deep” originates from the last line of Langston Hughes’s 1921 poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” in which Hughes alludes to the long history of movement and forced displacement in the African Diaspora.

With reference to the rivers which have been prominent in landscapes of change and renewal, he concludes “My soul has grown deep like the rivers.”

Souls Grown Diaspora follows a subsequent wave of ten disparate contemporary artists: most of whom are self-taught, some of whom have studied at Pratt, the School of Visual Arts or the Fashion Institute of Technology, and all of whom have encountered racism and marginalization in their careers. The exhibition, the design of which is inspired by the traditions of yard art and quilt-making, includes a wide range of media: painting, drawing, photography, sculpture, textiles, and jewelry, alongside a collection of archival ephemera and research materials. Because over half of the artists make and record music as part of their art practices, the exhibition also includes a soundtrack.

Together, the works in Souls Grown Diaspora explore every day traditions and engage actively with other contemporary artists of their day. Looking collectively at these diverse artists—some dearly departed, many still actively creating, some living with HIV, others sober and in recovery, variously identifying as straight, bisexual, gay, and trans—a number of themes emerge.

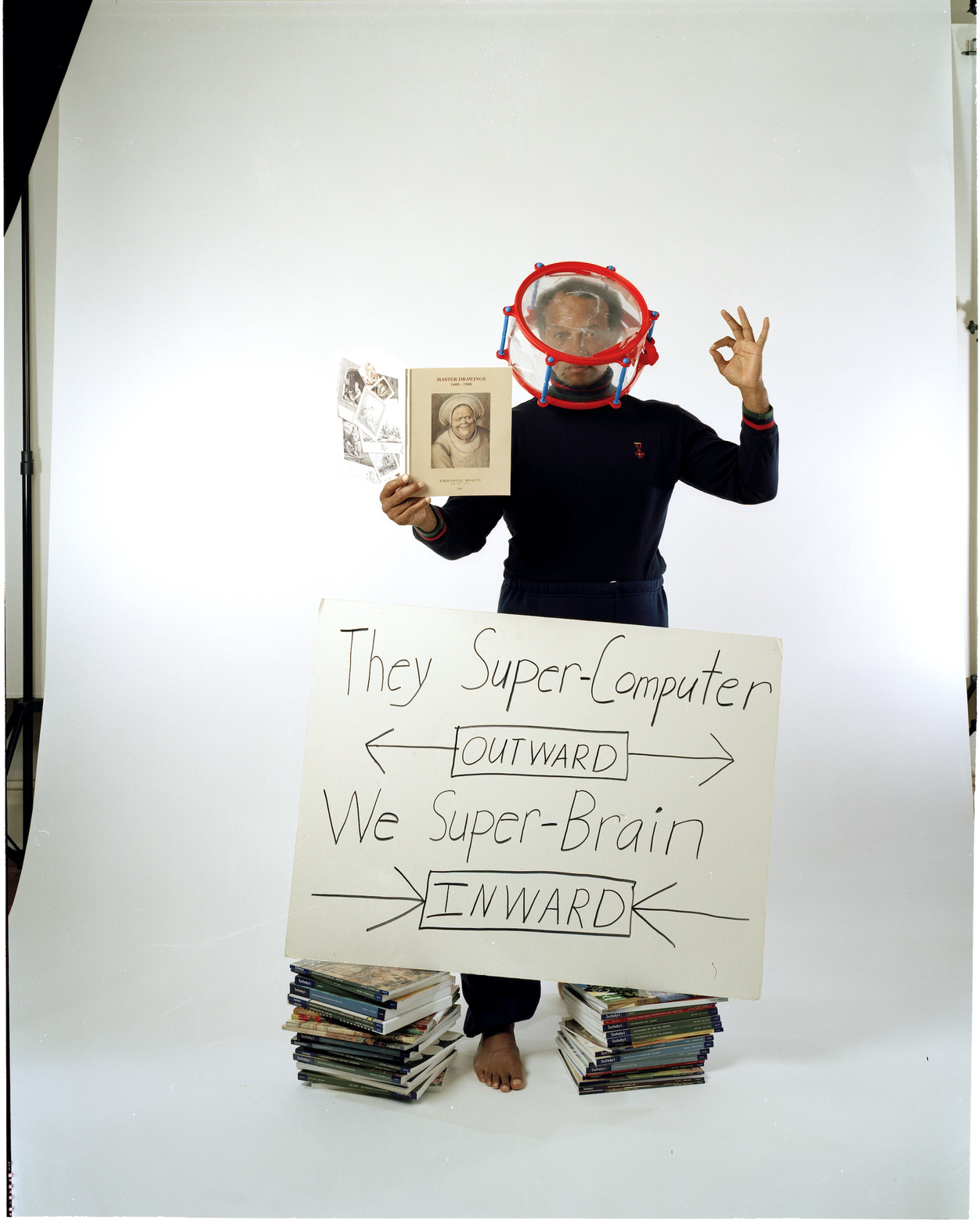

Alvin Baltrop’s photography captures the heyday of the West Side Piers and their parades of men. Raynes Birkbeck’s drawings, paintings, and sculptures delve into multi-layered, orgiastic narratives. Stephanie Crawford, well known in the 1980s Downtown New York scene of the Pyramid Club as a fantastic jazz singer, also paints the flowers and candy any diva would come to expect as tokens of appreciation from adoring fans. Curtis Cuffie became well-recognized in the 1990s for his street installations around Astor Place and the East Village, and the exhibition features some of his subsequent assemblage sculptures. Still today, Otis Houston Jr. creates his paintings, signs, and sculptures and delivers regular performances from a spot under the entrance to FDR Drive at 122 Street.

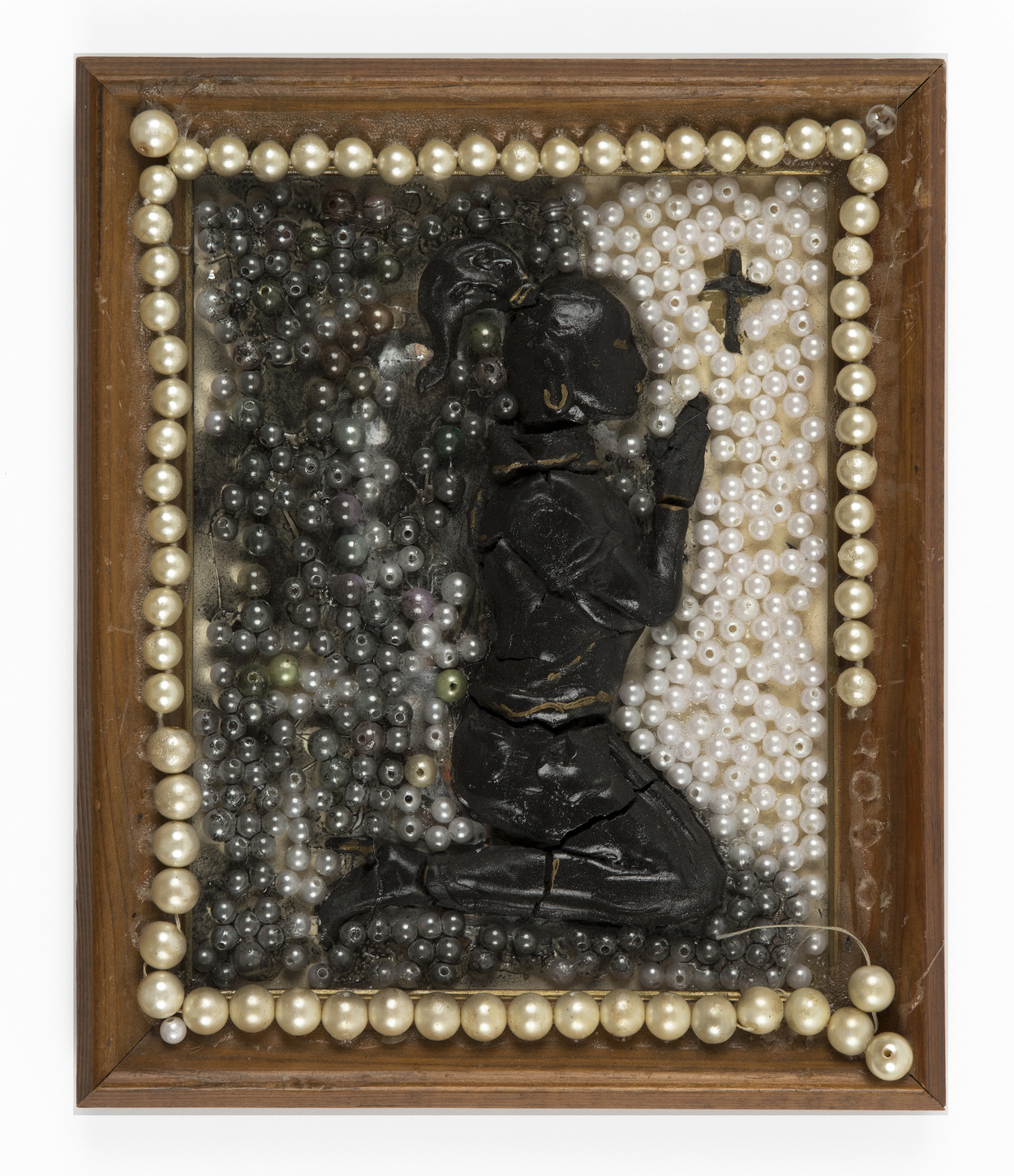

Dapper Bruce Lafitte drafts elaborate drawings depicting his ever-shifting persona and the world of New Orleans. Reverend Joyce McDonald’s sculptures, made from ceramics and found objects, track in her words, her “path from the shooting gallery to the art gallery.” Sara Penn was well known for her Tribeca shop, “Knobkerry,” where she presented work by David Hammons alongside various textiles, beads, and other artifacts from around the world, and in turn the entire shop was a total artwork in itself. Frederick Weston creates elaborate collages culled from binders full of imagery he cuts from magazines, archived for years until finding their way into his work. The legendary polymath Wesley Willis released numerous albums and created spectacularly intricate drawings of highways and urban landscapes.

Baltrop and Weston’s championing of the use of vernacular photography naturally leads toward an embrace of social media, by Weston himself and by Houston Jr. and McDonald, who create work across multiple platforms and accounts.

Handwritten words and texts populate many of the artworks—conveying humor, urgency, abstraction, and politics with everyday language.

Other themes in the exhibition, such as the home as studio, the street as studio, public housing, SROs, homelessness, and mental health issues, are especially important given the tremendous impact of these circumstances on the lives and work of these artists.

In 1994, I was in a mixed-media painting class at the Rhode Island School of Design with Kara Walker. I’ll never forget a comment she made about her journey as an artist, from Atlanta, Georgia, to RISD—“up North to freedom. She was kidding, in the way her work often kids, but it marked the first time I had considered the historic phenomenon of that mass migration. Gathering the work of these ten artists into an exhibition acknowledges their individual practices while also placing the artists within an important larger social context. By foregrounding the lasting effects of the Great Migration on the timeline of American contemporary art, I hope the exhibition helps initiate the compilation of a collective narrative, one that serves as an entry point into the lives and practices of often-overlooked visionary artists.

Whether self-taught or formally trained, each artist has merged the urban environment and deep family histories from the American South into a new Pan-African identity and aesthetic.

Effectively channeling their personal experiences and ideas into a dialogue with larger social issues, the artists of Souls Grown Diaspora are both deeply individual and conceptually linked.

Having worked on the margins of the art world for most of their careers, some of these artists are now entering into the contemporary dialogue through the attention of young curators and galleries, or their work has begun to reach a much greater level of attention posthumously. But as this exhibition underscores, these artists have always been in conversation with the vanguard artists of the day and have never thought of their work as less vital or important because of its development outside the bounds of the mainstream. In the words of Stephanie Crawford: “I think it’s time for some kind of declaration here and to toss the dice of truth and everlasting beauty. I am an absolutely extraordinary 76-year-old African American post-op transgender vocal jazz musician. And I have lived long enough to tell it. Or rather sing it. I am no longer ashamed. Or afraid of you. My life story as a gay transgender person of color is at once painful, sublime, ridiculous, heartstoppingly beautiful and ultimately victorious.”

Sam Gordon

Open Call Exhibition

© apexart 2020

1. The records of the Algerian Ministry for Mujahideen (veterans) places the number of women combatants during the war at 10,949. In 2014, Nassima Guessoum made the film 10949 femmes dedicated to women veterans.

2. Fadéla Mesli quoted in Natalya Vince, Our Fighting Sisters: Nation, Memory and Gender, 1954-2012 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015), pp. 96-97.

3. See James D. Le Sueur, “Torture and the Decolonisation of French Algeria: Nationalism, ‘Race’ and Violence in Colonial Incarceration”, in Captive and Free: Colonial and Post-Colonial Incarceration, ed. Graeme Harper (London: Bloomsbury, 2002); Raphaëlle Branche, “The French Military in its Last Colonial War: Algeria, 1954-1962 – the Reign of Torture”, in Interrogation in War and Conflict, eds. Christopher Andrew and Simona Tobia (London: Routledge, 2014).