In 2013, Edward Snowden's disclosures of the NSA's international surveillance programs fundamentally changed how we understand our channels of communication. Snowden presented evidence, published in a series of articles by journalist Glen Greenwald and exposed through Laura Poitras' Oscar-winning documentary, CITIZEN FOUR, that revealed an international system of email, SMS, and web browsing surveillance.(1) Despite this egregious invasion of privacy, western civilization has embraced surveillance over the past generation.(2) Governments increase their observation of almost every aspect of our lives, and communications corporations continue to feed our insatiable appetite for faster, more expansive information sharing. As social citizens, we embrace these methods, happily diverting more and more of our daily interactions to online platforms, dedicating hours to networking, stalking, and gossiping.(3) Organizations and governments' shockingly invasive behavior is being mirrored, even supported by individual users. Systems of information function as infrastructures of control and vice versa. Users are finding creative applications of these systems in order to undermine their function, call attention to the problems they perpetuate, or re-imagine this international network of cameras and GPS devices as a method of subversive communication. Profiled: Surveillance of a Sharing Society unites six contemporary artists who are working within these societal contradictions. Their working methodologies employ social media and user interfaces such as Google Street View to call attention to concerns and possibilities around our constant state of both wanted and unwanted exposure.

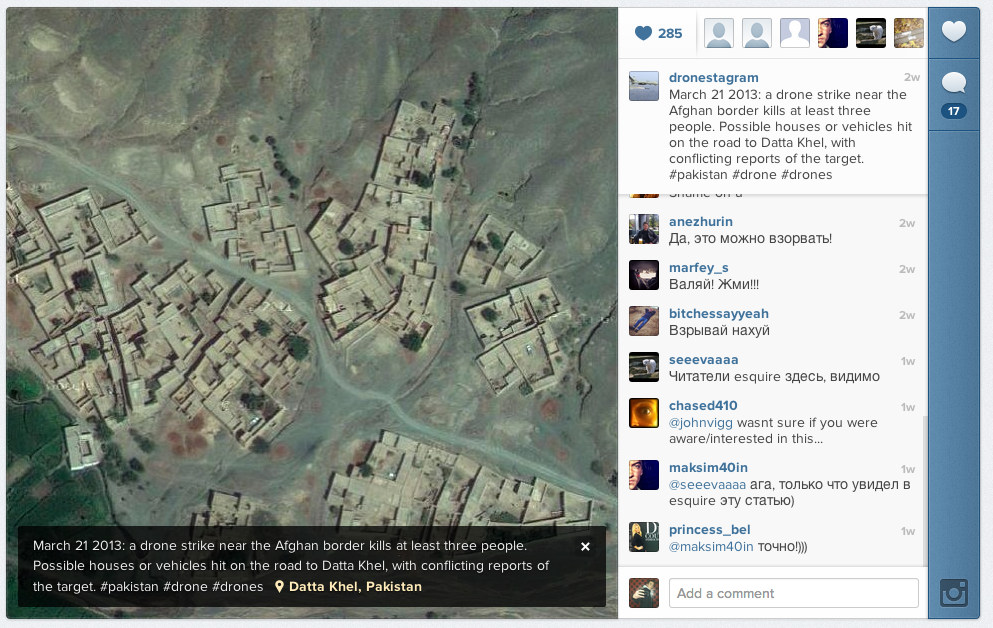

James Bridle’s Dronestagram (2012-ongoing) is an Instagram account where he posts aerial images from Google Satellite of locations where covert drone strikes have occurred following reports by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism. Bridle's images are devoid of the horror of the strike's aftermath, removed from the news journalism context in which we are more accustomed to encounter them. Whitewashed through the app's universal design, the images lose some of their power, even as they reach hundreds more viewers. Bridle uses the social media platform as a form of critical photojournalism, he is simply re-posting readily available images of geographical locations and information freely available in the public domain. Initially provocative, Bridle creates social awareness of violent drone activity by actually revealing nothing at all. The issue at hand – the lack of any actual images of the aftermath of the strikes – is more subtle, often completely missed by the comments on Bridle's account, ranging from shock at the ìcontent,î appreciation of his work, and often a complete misunderstanding of both.(4)

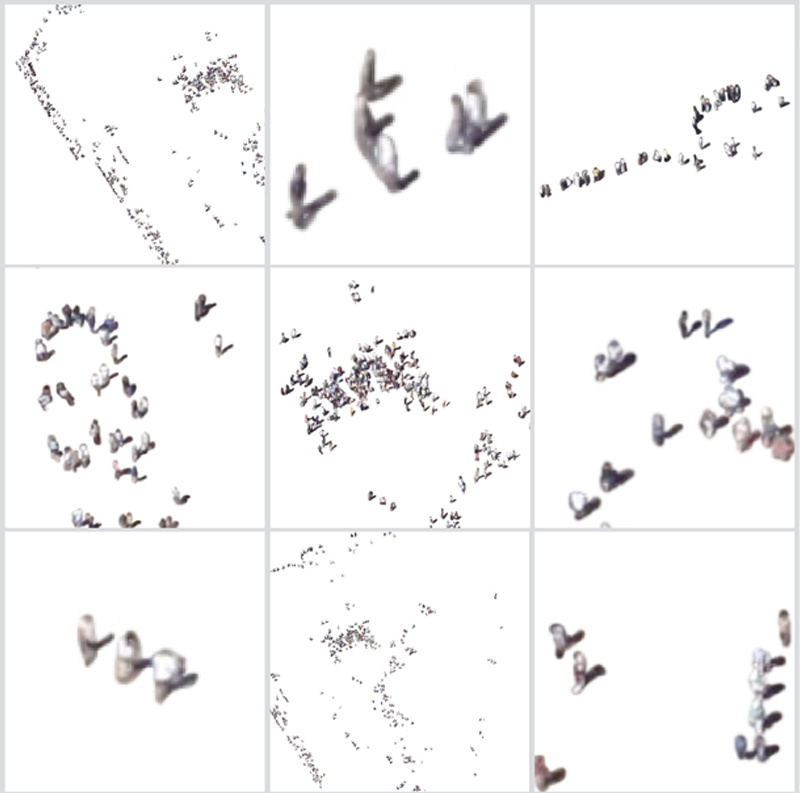

Jenny Odell negotiates the complex arguments around public aerial photography. Like Bridle, she questions what these satellite images actually represent. In her series of photographs, All the People on Google Earth (2012), Odell removes the backgrounds on images from Google Earth, leaving only the insect-like abstractions of people. Little information can be gleaned about the individuals, an argument Google uses when claiming that such photography is not an invasion of privacy. Similar arguments were made by the NSA, who claimed that only metadata, not names and phone numbers, are being transcribed. Odell's photographs adjust the conversation from the expectation of privacy to the reality of mass surveillance. What are our rights if we do not exist as individuals? Are these images indicative of a greater harm?

Also culling imagery from Google's mapping software, Paolo Cirio’s Street Ghosts (2012-ongoing) return the figures caught on Street View back into the physical urban landscape, posting life-size vinyl appliques of subjects walking, standing, or working. Sharp reminders of the constant public-ness of our daily mundane actions, Cirio pushes the boundaries of acceptable image usage, calling attention to the types of information readily available to stalkers, creative and otherwise. Simultaneously, his Street Ghosts immortalize their unsuspecting subjects, functioning as an eerie genre painting of daily urban life.(5) Both Odell and Cirio force the viewer to consider their expectations of a private presence in public space. Does Google's assurance that images are time-delayed by a few months provide protection of privacy? Could friends, family, co-workers, or enemies of the individuals photographed be recognized later? How comfortable would you be having a photographic record of your presence in a place?

Of course surveillance of public spaces has existed long before Google began photographing topographies in 2007. Strategically placed cameras connected to closed circuit televisions (CCTVs) have "protected" ATMs, city streets, even private homes since the 1990s. Julia Scher has been calling attention to these unseen observers since then. Mothers Under Surveillance (1993) combines live footage from the gallery space with a recording of elderly women in a senior care facility. Creating a psychologically unsettling relationship between the gallery visitor as at once the surveyor and surveyed, Scher prophesies the psychological rush we feel when watching live cams, perusing our colleague's social media pages, and observing our friend's and families' lives unfold through silent visual communication.(6) Again, public and private are re-analyzed as the viewers find themselves perhaps more expected to be recorded while in an art gallery, but more uncomfortable to be watching others in a senior home, a place where we would assume a greater level of privacy. How the artist found the footage, and was able to pirate it for the purposes of her work, cause us to wonder how these videos are secured, how they are watched, and by whom.

Jens Sundheim, with the assistance of Bernhard Reuss, found agency in being documented on these same kinds of security cameras. For his ongoing project The Traveller (2001-ongoing), Sundheim located the exact placement of over 600 surveillance cameras in 17 countries and positioned himself in their view while Reuss linked his computer to the CCTV's stream and took a screen shot of his partner, revealing the ìweak linksî of the seemingly impenetrable front of the police state. Sundheim used the official response by the owners of the camera – arrests, interrogations by police (even the FBI during a visit to New York) – to question what these cameras are protecting and what they prevent. Although the artist's image is always captured standing naturally in a public place, his image is the property of the owners of the CCTV cameras. It is in capturing the images of his presence before the cameras, not simply occupying the space, that incites the anger of the surveyors, a markedly different reaction from Google Earth's negotiation of an acceptance in using the interface as a method by which to have one's image included in the landscape.(7)

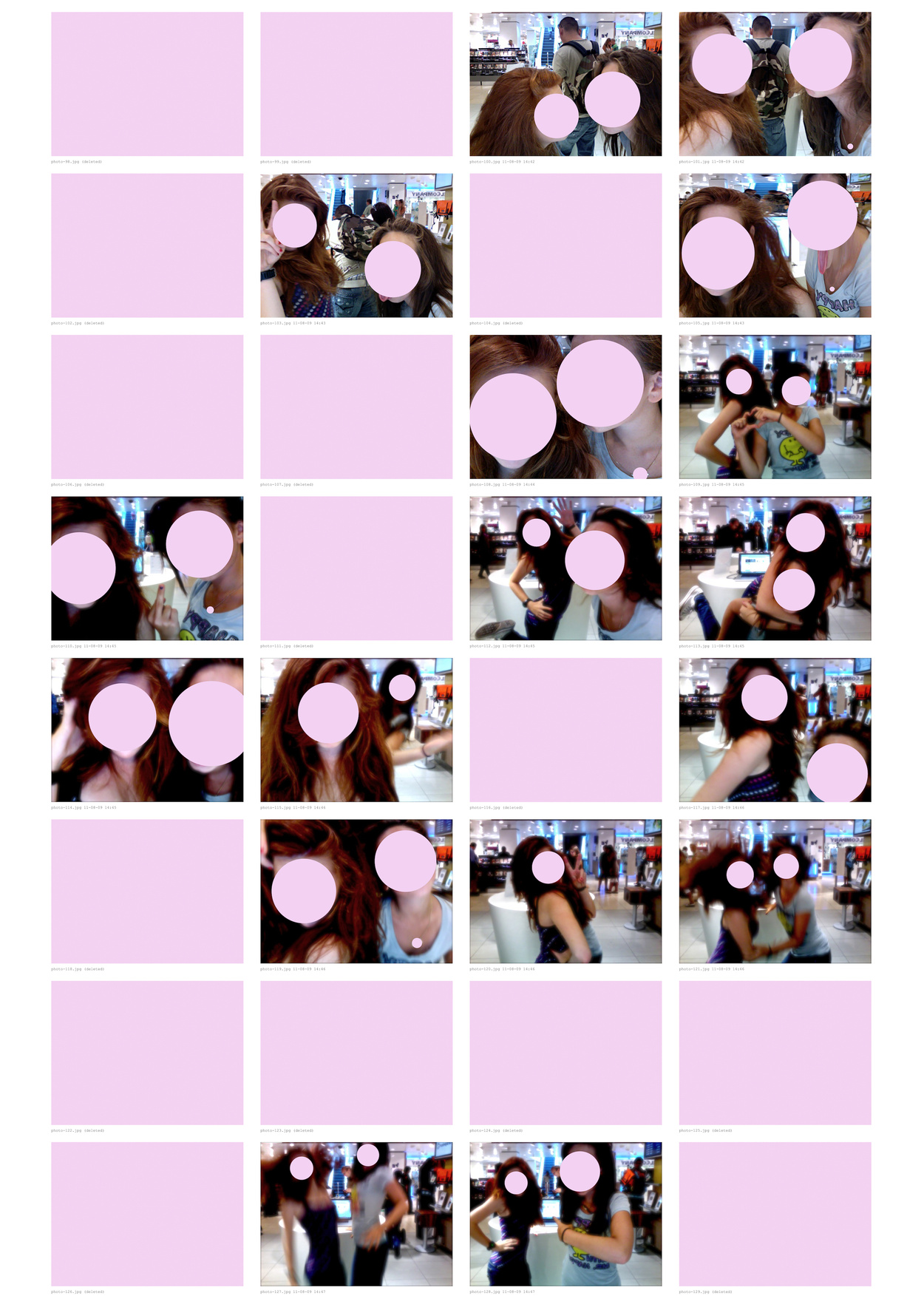

This delicate balance of wanted and unwanted observation is the crux of what I call "The Society of Surveillance." Willem Popelier shows how we willingly feed the social media culture in Showroom Girls (2011), an archive of selfies taken by two teenage girls in a computer showroom, uploaded to Twitter and left on view for the next shopper. Through the twitter feed The artist was able to learn more and more about their daily lives, interests, and network. Using the two girls as a sample case, Popelier illustrates how easy it is to occupy the role of the stalker.(8)

In 2011, Cirio pirated over a million Facebook profile pictures, organized them by gender and facial expression, and posted them on the artist's self-designed "dating website." Days after the site went live, outraged "users" demanded that their images be removed from the website. What followed, documented in news footage and correspondence between the artist, legal agencies, and the Facebook Corporation, is an amazing analysis of what happens when information users contribute to a public forum is re-purposed with a different message. For hundreds of users, that another entity could appropriate their images (Cirio only pulled photographs, not names or other data, although he could have copied complete profiles just as easily) seemed unfathomable.

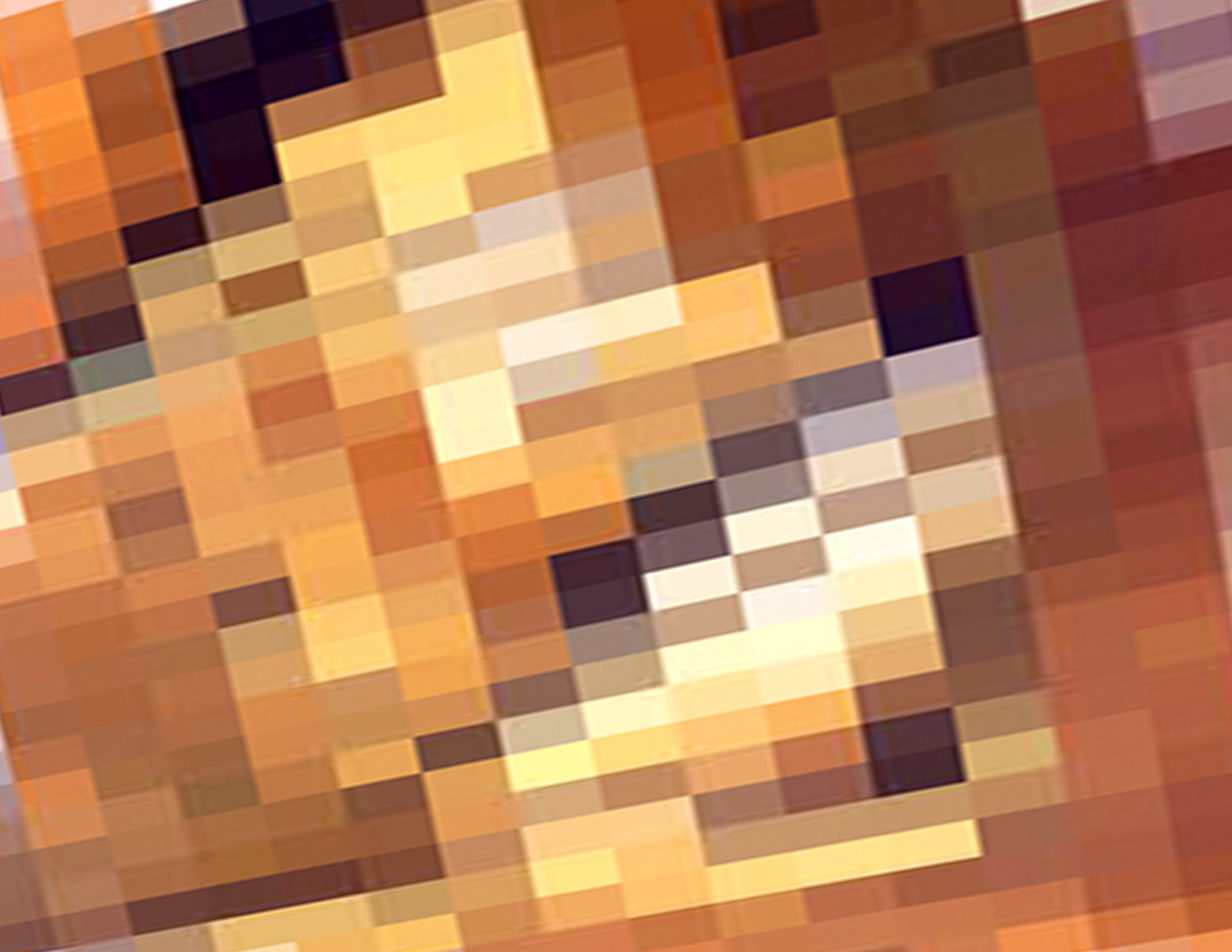

Who has permission to view images is a key method of controlling information from others. A key aspect of The Society of Surveillance is the contradictory restrictions placed on image and information access. The tightly controlled release of information around the alleged assassination of Osama Bin Laden in 2011 by U.S Navy S.E.A.Ls is visually analyzed in Popelier's Obscured Classified Document (2012). Popelier reproduces a cropped close up of a document visible on Hillary Clinton's lap in the well circulated "situation room" photograph. Purported to document the Obama administration witnessing the invisible assassination, the photograph took on iconic status, replacing any documentary evidence of the assassination. Popelier's work, showing the pixelated document deemed "top secret" by the White House, replaces the well-circulated photograph of the meeting as a representation of what we aren't allowed to see.

For all the information that the NSA and corporate data-mining systems obtain, what is released to us, the subjects, is highly censored. The amount of confidential data shared between governments and networks of secret contractors has reached record heights.(9) The balance of power has shifted heavily in favor of governments who know far more about us as individuals than we are allowed to know of their motives and actions. Yet this does not mean we have become a society content to be passively surveyed. International communications systems and data sharing has allowed us to more fully realize the power of the image, seek our own paths to knowledge, and even claim corporate information systems as our own. The artists featured in Profiled question each of these complex systems as we circulate images of ourselves and others, even as our own images are being spread and controlled beyond our direct actions. The questions they ask are not as binary as right and wrong, rather they try to more tightly define laws, seek loopholes, and recognize realities.

Mary Coyne

Open Call Exhibition

© apexart 2015

1. See Glenn Greenwald No Place to Hide (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2014). Almost a decade before the Snowden leaks, USA Today reported the NSA's covert gathering of millions of phone call records. Leslie Cauley, "NSA has massive database of Americans' phone calls," USA Today May 11, 2006. http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/washington/2006-05-10-nsa_x.htm [accessed March 9, 2015].

2. John McGrath, Loving Big Brother: Surveillance Culture and Performance Space (London: Routledge, 2004), 1.

3. Social media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram are now used by a shocking sixth of the world's population, with the majority of activity in the U.S, Europe, and Japan. The Statistics Portal,"Number of monthly active Facebook users worldwide as of 4th quarter 2014 (in millions)" http://www.statista.com/statistics/264810/number-of-monthly-active-facebook-users-worldwide/ [accessed March 11, 2015].

4. Instagram and Facebook do not hold copyright to images posted on their websites or apps, but do hold a type of non-exclusive licensing agreement to which users agree when initially creating their accounts. These agreements allow the social media sites to re-publish and distribute images without the explicit consent of the original source. Facebook, "Terms of Service," https://www.facebook.com/legal/terms [accessed April 22, 2015]; Instagram "Terms of Use," https://help.instagram.com/478745558852511 [accessed April 22, 2015].

5. Google Maps "Privacy and Security" https://www.google.com/maps/about/behind-the-scenes/streetview/privacy/ [accessed April 20, 2015].

6. Bruce Nauman's use of closed-circuit television and isolation chambers is an important precedent to Scher's work in this exhibition.

7. Google Earth provides suggestions for users to include images of themselves on the website, instilling a belief in a user-friendly, personalized and "friendly" aspect of the corporation.

8. The Twitter accounts have since ceased to be active.

9. Brad Plummer, The Washington Post, "About 500,000 private contractors have access to top-secret info." June 11, 2013 http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2013/06/11/about-500000-private-contractors-have-access-to-top-secret-information/ [accessed March 11, 2015].