FROM IRACEMA TO THE GIRL FROM IPANEMA

The first chords of the famous song set the scene: on a sandy beach, a beautiful woman parades her sweet swinging stride on her way to the sea. Although "The Girl from Ipanema" did not establish the cliché of the Brazilian woman, its success helped spread a certain image of Brazil. The associations about Brazilian womens' sensuality vary from intriguing to reproachable according to the woman or the interest of the interlocutor. The 12 artworks gathered in this exhibition defy such stereotypes and open a door to the multiplicity of lived realities in a country as vast as Brazil.

The fantasy that Brazil's territories and women are ideal for exploitation has been promoted across 20th century tourism industries and in a 2019 speech by President Jair Bolsonaro ("whoever wants to come here and have sex with a woman, be my guest"). It's a concept that derives from and perpetuates a brutal process of colonization. The objectification and obliteration of Indigenous peoples is not exclusive to Brazil, but here it has left indelible marks; centuries later, the struggle for land ownership continues among Indigenous citizens. The artwork Indiogente, Indigente, Indigen-a-te by Arissana Pataxó sheds light on how colonialism's "civilizing" mission dehumanized the Indigenous communities, often classifying them as hypersexual and savage. Brazilian philosopher Sueli Carneiro summarizes the impact of this period, claiming that colonial sexual violence is the "cement" of the racial and gendered hierarchies which have formed Brazilian society.1

Shortly after the arrival of the Europeans and the subsequent decimation of the Native peoples, the largest human trafficking operation in the Americas began; between the 16th and 19th centuries, almost 5 million Africans were forcibly removed from their homelands to be commercialized, enslaved, and brutally assaulted. African women and their Brazilian descendants were – and are – primary victims of that violence. Great efforts have been made to assert the myth that the horrors which took place between masters and enslaved people were consensual, resulting in a "racial democracy" where White, Black and Mixed-race people in Brazil coexist in harmony and without racism. In truth, if we are a blended society, it is because of the rape of Black women in a system dominated by elite White men.

In this country there is an ongoing project of racial whitening and genocide of Black people, which is exemplified by the increase in HIV among that population. In her performance Cura, Micaela Cyrino focuses on prejudice and the search for the cure—not for the disease caused by the virus, but for the stigma related to it and the fact, neglected by the state, that the Black community suffers the highest number of AIDS-related deaths in Brazil.

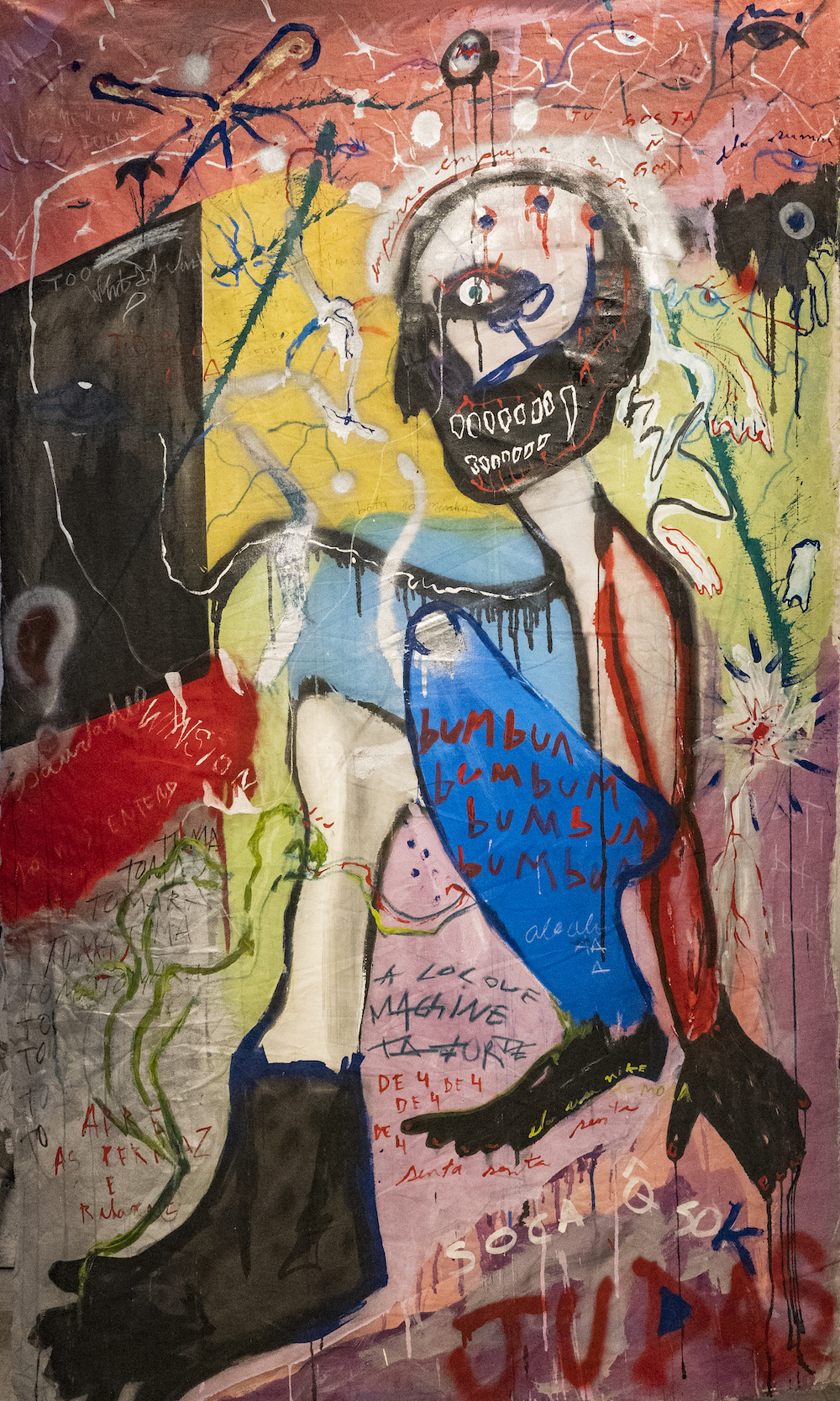

Still, there are even more harmful sterotypes of Black Brazilian women that stem directly from the country's history of slavery. For example, the abominable concept of "export-quality mixed-race women" is rampant across both foreign and local imaginaries. Whenever they reveal their bodies, as when performing in events such as the Carnival (a cultural expression often reduced to the folkloric image of half-naked dancing women), Black women are interpellated "not only as sexual objects, but as concrete evidence of the 'Brazilian racial democracy.'"2 Brenda Nicole's painting, Volume 7, features a person dancing to funk and punk music with words – some of them obscene – scrawled in the background. Discussions of sexually-explicit lyrics and choreographies often question the presence of misogyny: debating whether cultural expressions like Carnival and funk music liberate women through facilitating personal expression, or objectify them.

DOMINATED NATURE

While both traumatic episodes – colonization and slavery – forged the trope of the sensual and promiscuous Brazilian woman, they also illustrate the Marxist notion of history as a process of objectification or domination of nature. The role of women in the reproduction process (and their exclusion from the production processes) acknowledged us – and persecuted us – for our unique relationship with magic and nature, something "central to women's subsequent objectification and conquest by men."3 This thought permeates Alfabeto Cibernético by Fernanda Sternieri, a tapestry in which she elaborates on who we were before language and, therefore, before objectification. Through this traditionally-female artform, the artist presents a contemporary inversion, focusing on how cybernetic vocabulary resembles guttural, pre-lingual sounds, such as "kkkk" to express laughter.

Of course, the phenomenon of objectification is not exclusive to Brazil, and the scapegoating of women, that they are to blame for all evil, has been going on at least since Eve and her apple. The installation W97M/MELISSA, by Vitória Cribb, recalls the 1990s, when e-mail accounts belonging mostly to White men – global executives – were easy targets for "Melissa": a computer virus disguised as a stripper that, with a suggestive message, spread like wildfire by enticing men. Cribb reminds us that Melissa is a Pandora of the digital world, and that the avatar of the lascivious, conniving woman continues to be reproduced.

CONTROLLING IMAGES

American sociologist Patricia Hill Collins' concept of "controlling images" might be one of the keys to understanding the formation of the stereotype of Brazilian women — particularly in relation to Black women, and Latina women to a lesser extent. Since the authority to define social values is an important tool of power, the purpose of stereotypes is often the maintenance of control and oppression. When objectifying, men immediately place themselves as subjects, while women become the Other (to Simone de Beauvoir, "the second sex"). In this case, a clearly masculine and Eurocentric subject creates an objectified stereotype which allows him to control narratives around certain bodies and blame the victims: if Brazilian women are perceived as sensual, it is presumed that their bodies are available. Therefore, by this faulty logic, the violence suffered by women is their own doing.

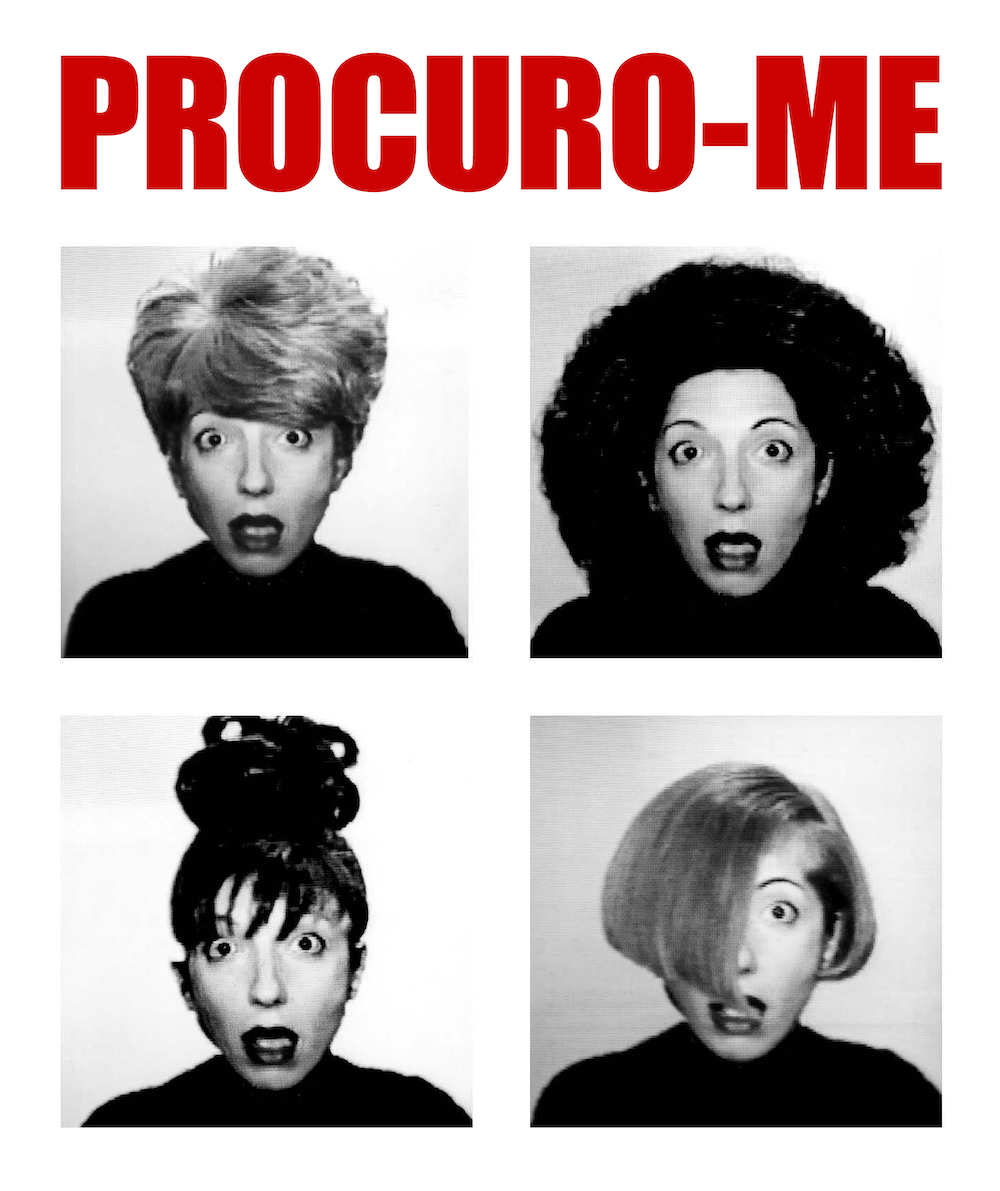

National identity can be fragile in countries that have been colonized, which facilitates the application and solidification of a controlling image. A considerable part of such populations do not know their heritage: few Black people have information about their ancestors, and while White women often mention their European ancestry they are never considered as such in Europe. Brazilian women, in general, also struggle to identify as Latinas—possibly because they do not share the Spanish language with the majority of their neighbors. Lenora de Barros' work, Procuro-me / Procura-se (Wanted / Wanted By Myself) deals with the permanent search for an externally-validated identity. In The Water Fountain, June Canedo de Souza, a Brazilian artist living in the USA for over 20 years, responds to the loss of identity after traumatizing events, such as sexual harassment, a violent household, and the hardships of immigration. Canedo de Souza's performance brings to light the fatigue imposed by these situations.

If violence is inscribed within the image-creation of Brazilian women, it also represents its worst consequences. Brazil is among the countries with the highest rates of rape and murder of women; the macabre scenery where this is most frequent is in the home itself. Red shoes, held by a chain, read "stay at home" – a phrase repeated to exhaustion during the pandemic lockdown – composing There's no place like home, by Camilla D'Anunziata. The Covid-19 pandemic resulted in an increase in domestic violence rates across the country. To many women, home is not a safe haven.

The streets also pose significant risks, especially to vulnerable LGBTQIA+ communities. Lesbians, for example, suffer the violence and fetishization of their sexuality. In the performance Cadê minhas irmãs? (Where are my sisters?) Benedita Arcoverde reacts to the hideous data revealing Brazil as the nation where the most transgender people are murdered. Relatedly, Brazil is also the world's largest consumer of pornographic videos with transsexual themes, making evident the close relationship between the bodily objectification and violence.

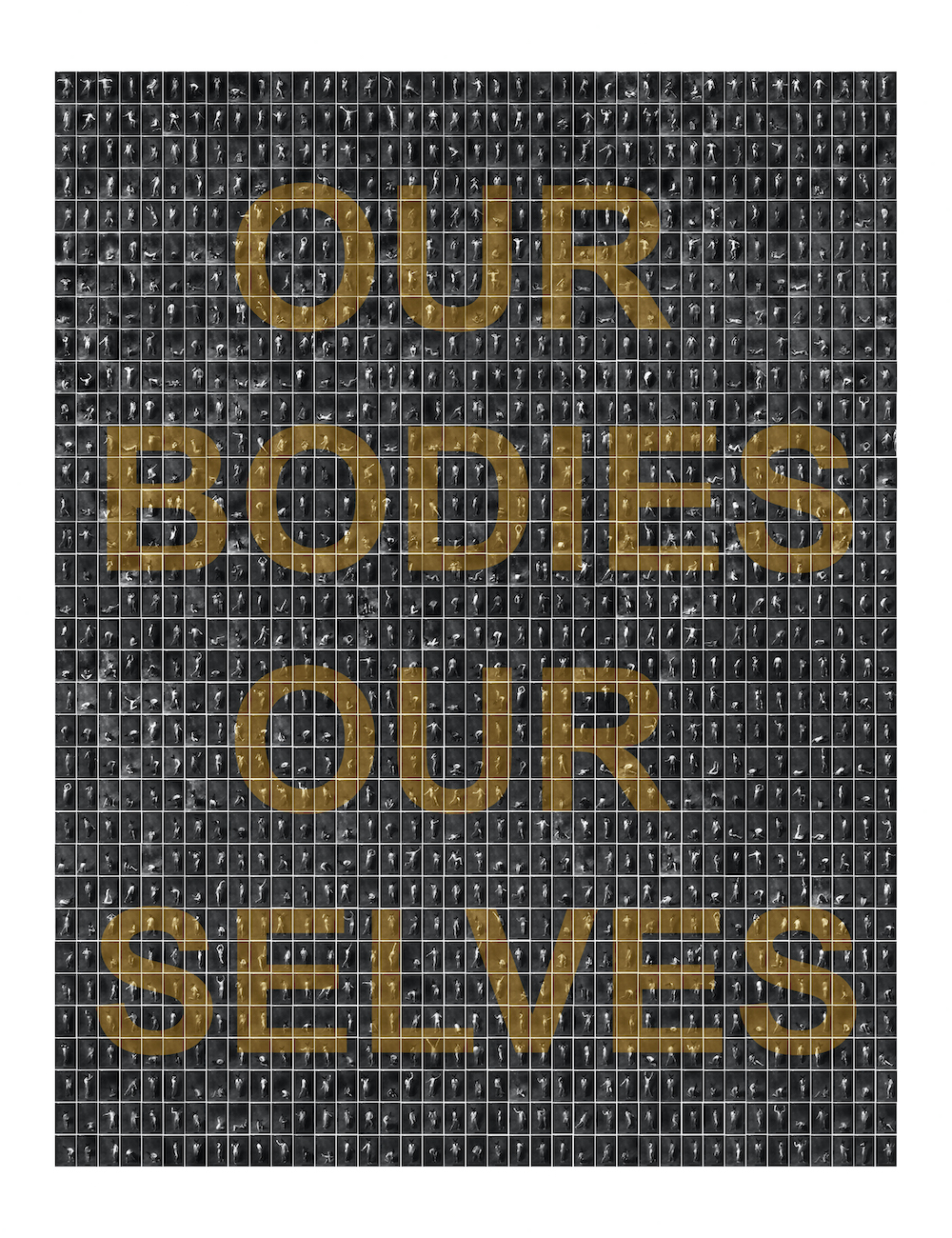

The situation of Brazilian women abroad is not any better. The digital photograph Our Bodies, Ourselves, derives from the indignation felt by artist Juliana Manara in response to the statistics showing that 4 out of 5 Brazilian women living in London fall victim to domestic violence. Controlling the bodies and the narratives of women is an effective form of maintaining their oppression. Not by coincidence, the phrase "I love Brazilian women" is uncomfortable for many of us, something corroborated by the neon sculpture Brazil, by Santarosa Barreto. Although apparently affectionate, this claim casts exoticized assumptions upon its subjects, and in effect corroborates Collins' concept of controlling images.

The internet is an open field for the dissemination of these images; simultaneously, it enables new depictions. Social media is, for those who venture to stand up to trolls and censorship, an opportunity to break away from the traditional figures of magazine covers. Milena Paulina photographed hundreds of fat women who radically challenge the standard of erotic nudity. O Grito is the creation of a new identity, contemplating a range of people who had never seen themselves represented within the aesthetic ideal. Nevertheless, even algorithms reproduce controlling images: the artist's Instagram account is frequently censored.

Through the collection of these 12 works, Oh, I Love Brazilian Women! offers another perspective on the disparate experiences and identities of Brazilian women. With optimism, these works can represent a step forward in terms of freedom, the torch that we – and only we – carry in our hands.

Special thanks to Sesc Art Collection, Coleção Museu de Arte Moderna MAM São Paulo, Gomide & Co., vandlart.

Luiza Testa

Open Call Exhibition

© apexart 2022

1. Sueli Carneiro, “Enegrecer o feminismo: a situação da mulher negra na América Latina a partir de uma perspectiva de gênero,” in Pensamento feminista: conceitos fundamentais ed. Heloisa Buarque de Hollanda (Rio de Janeiro: Bazar do Tempo, 2019), 313.

2. Lélia Gonzalez, Por um Feminismo Afro-Latino-Americano: Ensaios, Intervenções e Diálogos (Rio Janeiro: Zahar, 2020) 59.

3. Patricia Hill Collins, Pensamento Feminista Negro: conhecimento, consciência e a política do empoderamento, trans. Jamille Pinheiro Dias, 1st ed., (São Paulo: Boitempo Editorial, 2019).