I acknowledge that apexart's physical gallery space is located on the ancestral lands of the Lenape (Lenapehoking). I honor the deep significance these lands hold for Lenape past, present, and future, just as I acknowledge and honor the homelands of all the artists represented in this exhibition. Decolonization efforts begin with recognition - recognition of lands' original inhabitants, recognition of the violence colonizers perpetrated against Indigenous peoples and their land, and recognition of the survivance (survival + resistance) of Native cultures.

Decolonizing the arts must also include privileging the voices and input of Indigenous artists. To that end, I would like to thank the artists participating in this exhibition - Demian DinéYazhi', Marcella Ernest, Maria Hupfield, Elizabeth LaPensée, Natani Notah, Sheldon Raymore, Dyani White Hawk, and Jolene Nenibah Yazzie - all of whom read earlier drafts of this essay, suggested revisions, and ultimately approved the final version. As a non-Native curator, this part of the editorial process was particularly crucial, and I am grateful for the time given and expertise shared by the artists.

"The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex."1

With these words, the Nineteenth Amendment guaranteed women in the U.S. the right to vote, a feminist victory recently celebrated during the amendment's 2020 centennial. But the language of the legislation evinces a more complicated, less acknowledged history: American Indians in the U.S. were not considered citizens until the 1924 passage of the Indian Citizenship Act.

Since voting rights were governed by state law, many American Indians were disenfranchised until 1962, when the last state granted Indigenous suffrage. Just two years earlier, in 1960, First Nations peoples in Canada gained the right to vote in federal elections without losing their treaty status.

The historical proximity of these decrees, the colonial geopolitical boundary lines to which they point, and the web of interconnections between feminism and Indigeneity that have been woven by Native North American artists in the years since provide the premise for this exhibition.

In her 1986 essay "Who is Your Mother?: Red Roots of White Feminism," Laguna Pueblo activist and scholar Paula Gunn Allen asserted: "If American society judiciously modeled the traditions of the various Native Nations, the place of women in society would become central... the elderly would be respected, honored, and protected as a primary social and cultural resource... [and] the destruction of the biota, the life sphere, and the natural resources of the planet would be curtailed."2 In other words, if settler American societies adopted the worldviews and gynarchical practices that characterized Indigenous communities prior to European invasion, those contemporary sociopolitical problems would be alleviated.

Today, issues regarding women's rights, elders' protection, and environmental concerns are critical for many North Americans, particularly in the contexts of the #MeToo Movement, the COVID-19 pandemic, and continued fossil fuel extraction. The artists in this exhibition, all of whom identify as feminists, grapple with the specific ways Native communities experience these and other concerns.

A four-poster suite produced by Demian DinéYazhi' (Diné) with R.I.S.E.: Radical Indigenous Survivance & Empowerment interrogates whitewashed conceptions of feminism—the false assumption that feminist principles and advancements have largely been developed by white women. Per the individual titles of the posters, these works highlight the significance of Indigenous Feminism, insist that we Decolonize Feminism, and remind us that Native communities have long practiced what could be termed Proto-Feminism, or No Wave Feminism. Placed near the gallery entrance, the posters establish the exhibition's position: concepts of feminism must be decolonized to account for the diverse experiences of people with varying subject positions, and the ideals of mainstream feminism echo aspects of longstanding Native worldviews. Another poster, Honor Indigenous Women, emphasizes the strength, resilience, and significant cultural contributions of Native women. Each of these works pairs archival photographs depicting Indigenous women with decidedly contemporary fonts, and some of the posters feature patterned backgrounds that evoke a pop art aesthetic while simultaneously referencing Native design customs. The juxtapositions underscore the dynamism and contemporaneity of Indigenous traditions, rejecting stereotypic assumptions that place Native North American culture in the past.

Dyani White Hawk's (Sičáŋǧu Lakota) painting, A Heathen's Penance (The Imposed Load) references Kateri Tekakwitha (1656-1680), an Algonquin and Mohawk woman recently canonized as the first American Indian saint. The snow and deeply hatchmarked walkway represent extreme penance practices that contributed to her untimely death, while the columns at left and right evoke her skilled quillwork, an Indigenous art form comprising softened porcupine quills. Catholics praised her diligence in producing this painstaking work, characterizing her industriousness as a Christian trait. But industriousness is a Native value that would have developed within her tribal communities. Just as Indigenous communities have long practiced ideals mirrored in mainstream feminism, this celebrated characteristic of a 24-year-old sainted Native woman preceded her introduction to Catholicism.

White Hawk continues to explore dynamic Indigenous traditions in Takes Care of Them. The series title suggests the role of women as cultural and communal caretakers, while individual subtitles – Wówahokuŋkiya | Lead, Wókaǧe | Create, Nakíčižiŋ | Protect, Wačháŋtognaka | Nurture – further emphasize the cherished roles of women in Lakota culture. The prints feature Plains-style women's dentalium dresses of varying designs, which White Hawk describes in generational terms; the minimal early style of the blue dress in Lead alludes to an older, grandmother figure, while the more contemporary gold dress of Create connotes a younger relative.

Sheldon Raymore's (Cheyenne River Sioux Nation) work reminds us that in most Native worldviews, gender is not a rigid binary. Prior to European invasion, Indigenous communities in the Americas allowed and even celebrated gender fluidity. Today, the term "Two-Spirit" broadly refers to Indigenous peoples who possess masculine and feminine traits.3 Raymore's Two-Spirit Tipi modifies the imagery of a nineteenth-century winter count, in which a wink'te (a Lakota term for people assigned male at birth who later take on the social/ceremonial roles of women) was recorded as having been killed. Winter counts are pictographic historical records, with symbols representative of approximately one year painted on deer or buffalo hides. The wink'te's gender fluidity and death are visually connected to the face above, which represents Raymore's own Two-Spirit alter-ego, PrEPahHontoz. The red handprint over her mouth is a common symbol for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW), referencing the staggeringly high rates of violence against Native women and Two-Spirits.4

DinéYazhi''s R.I.S.E. poster Decolonize Your Luvvv reproduces an 1877 photograph of Osh-Tisch ("Finds Them and Kills Them") and their wife. Osh-Tisch was an Apsáalooke Crow baté (a Crow term similar in meaning to wink'te) greatly respected by their community. They were among the last historical batés, because assimilationist U.S. agents enforced the adoption of rigid gender roles.

The imposition of a colonialist and patriarchal gender binary has had lasting effects on Indigenous communities—with contemporary consequences addressed by Marcella Ernest (Ojibwe) in Because of Who I Am. This short film recounts the experience and creative expressions of multidisciplinary artist Jolene Nenibah Yazzie (Diné/Comanche/White Mountain Apache), who dances in the Northern Traditional men’s category at pow-wows, an activity for which she has been bullied. Yazzie rejects heteronormative, anti-Two-Spirit gender concepts that have been adopted by many Native communities. Because of Who I Am translates a reclaiming of agency by actively defying ongoing discrimination.

The film includes stills of Jolene Nenibah Yazzie's own artwork, which is also on view in the exhibition. Sisters of War depicts three women sporting Diné men's war hats in a large-scale composition that presents these gender-fluid warriors with the punchy aesthetic of comic book heroines. While the women's feather-adorned hats evoke their status as Diné warriors – a role typically reserved for men – the red stars at their foreheads evoke the Náhookǫs star constellations, which include celestial beings of multiple genders that exist beyond a binary system.

Maria Hupfield's (Wasauksing First Nation) handmade creations speak to innovation, ability, strength, power, and beauty, often connecting sound with action. Double Punch, a pair of striking gloves with hand-sewn gold bells, places value on Indigenous women as capable leaders, athletes, and femme warriors in their communities, thereby rejecting – or striking down – the infantilizing, victimizing colonialist gender binary. The gloves further act as community-building pieces; they are living, breathing, jingling entities meant to be worn, linking artist, object, space, and participants in an inclusive system of reciprocal exchange.5

Natani Notah (Diné/Lakota/Cherokee) addresses ongoing violence against Indigenous women and Two-Spirits in Uncontrollable, Addiction, and Dignity. These soft sculptures display androgynous, abject forms that explore the connections between such violence and continuing U.S. colonialism. In using traditional appliqué beading techniques, Notah also considers the feminine aesthetic heritage of beading and its potential for healing.

Notah's Don't Bump Her draws a connection between violence against Indigenous women and harms done to the earth—violations that are imbricated per Indigenous belief systems in which the earth itself is held to be a feminine force. The car bumper in the work is associated with the oil industry, which has wreaked havoc on ancestral Native lands, while the title evokes a specter of violence—a car hitting a woman, perhaps, or more broadly the increased rates of violence against women in male-dominated camps that accompany the construction of pipelines, giving the feminist concern of this piece an ecocritical cadence.

Ecocriticism is further highlighted in Notah's Making the Disposable Sacred. Upon seeing media images of Standing Rock protestors wearing masks to shield themselves against police wielding pepper spray, she took dust masks from her studio and meticulously beaded them. Notah affirms her solidarity with those fighting to protect sacred land, and by using the healing process of traditionally feminine beadwork, she symbolically seeks to protect the protectors. In the time of COVID-19, Notah's masks have taken on a new meaning; Indigenous communities have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic and many campaigns to protect the elders have emerged.

Notah's NO' LAKES features mugs that reappropriate the "Indian maiden" logo of Land O'Lakes butter (since discontinued). By filling the mugs with black water and twisting the company's name, the piece evokes environmental concerns – that the pristine land and lakes ostensibly celebrated in this scene are no more – while simultaneously foregrounding stereotypic imagery of Indigenous womanhood. Such stereotypes are further unpacked in Heavy Heels, an assemblage featuring moccasins weighed down by a rolling pin.

Elizabeth LaPensée (Anishinaabe/Métis) takes up ecocriticism in With Songs to Pull Oil from Water. As in many Indigenous worldviews, Anishinaabeg have an inherent connection to the land, Aki (Mother Earth). Damage to the environment is damage to this terrestrial feminine being. In the print, harm to Aki is indicated by a glinting oil slick, over which androgynous figures sing restorative songs. LaPensée further addresses oil extraction, the damage it causes, and potential modes of Indigenous healing in the animation Hands to the Sky.

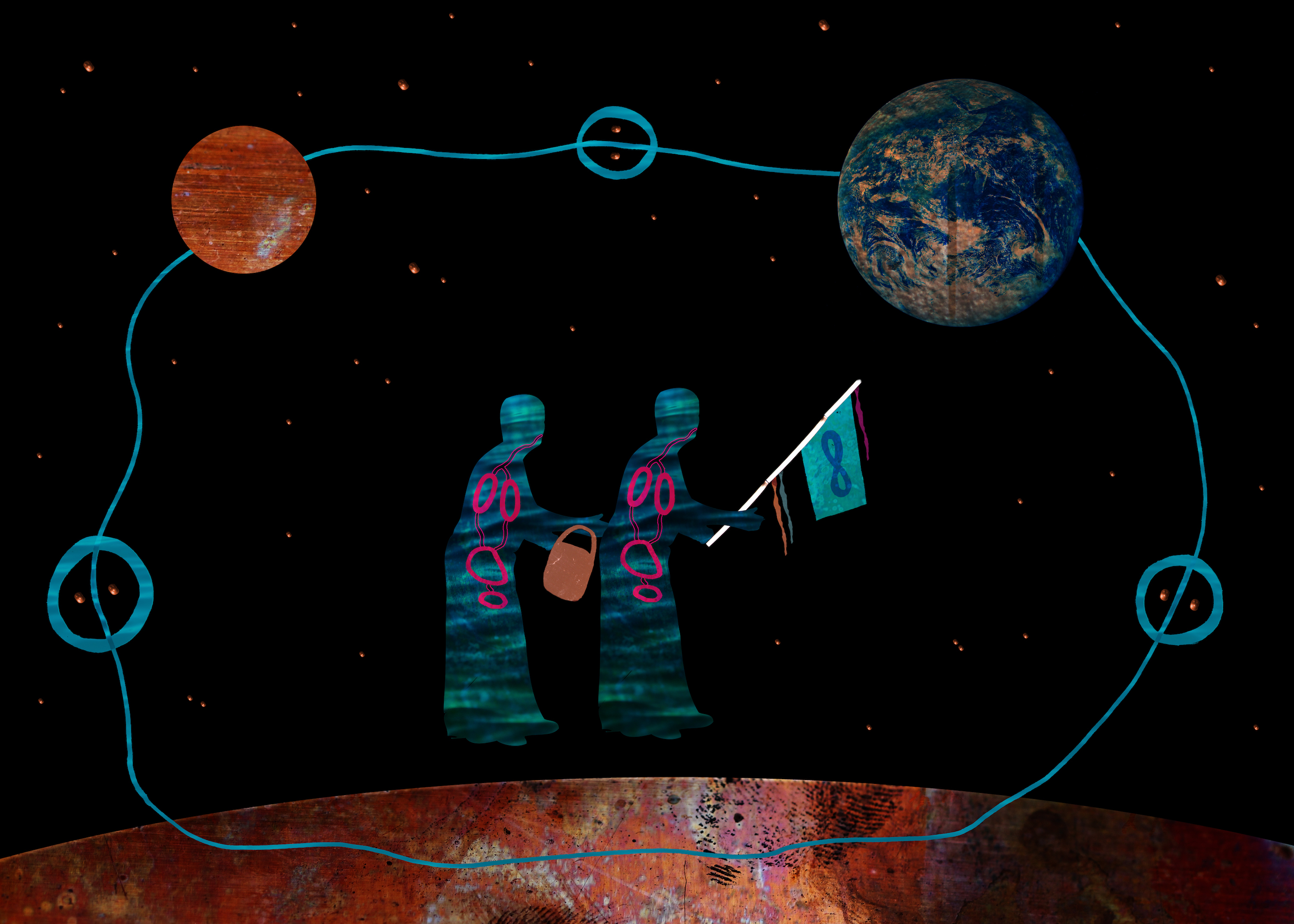

LaPensée's practice is circumscribed by Indigenous Futurisms, a set of concepts that connect Native ways of knowing with contemporary science fiction, particularly spacetime travel and post-apocalyptic narratives.6 In Our Grandmothers Carry Water from the Other World, the nurturing, feminine presence of the moon provides stability to the world via her light and the tides, as evoked by the lunar illumination and cyclical cosmos. We also see spiritual ancestors – the grandmothers – bringing water back to the Earth to ensure her healing and survival. Indigenous past, present, and future cannot be mapped along a linear timeline; Indigenous futures are inextricably linked with past and present, as is further explored in LaPensée's animation Returning.

The material and conceptual breadth of these projects and their historical and contemporary relevance suggest the discursive potential of Native feminisms. This exhibition showcases the aesthetic richness and political power of Native feminist art practices today.

Elizabeth S. Hawley

Open Call Exhibition

© apexart 2021

1. U.S. Const. amend. XIX, § 1.

2. Paula Gunn Allen, "Who is Your Mother?: Red Roots of White Feminism," Sacred Hoop: Recovering the Feminine in American Indian Traditions (Boston: Beacon Press, 1986), 211.

3. Sue-Ellen Jacobs, Wesley Thomas, and Sabine Lang, eds., Two-Spirit People: Native American Gender Identity, Sexuality, and Spirituality (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997).

4. Lakota People's Law Project, MMIW Resource Guide, https:// lakotalaw.org/news/2020-05-01/mmiw-resource-guide.

5. "Rupture and Repair: Indigenous Feminist Conversations, Statements, Questions with Maria Hupfield and Kim Anderson," 2020, Art Gallery of Guelph, https://artgalleryofguelph.ca/wp-content/ uploads/2020/11/Rupture-and-Repair-Transcript.pdf

6. Grace Dillon, Walking in the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fiction (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2012).