As the story goes, on November 27, 1985 (the day before Thanksgiving) gay activist Cleve Jones arranged a candlelight march to the San Francisco Federal Building to remember the death of Harvey Milk who had been assassinated only seven years earlier on November 27, 1978. Concurrently, the earliest and darkest days of the AIDS epidemic had descended on the gay community, with dozens of mysterious deaths every week from a disease that had a name but no cure—just a debilitating and heartbreaking death. Life for the LGBT community in San Francisco felt dire with threats seemingly piling up. Because of this, Cleve Jones asked members of the march to write the names of loved ones they lost to AIDS related illnesses, which were then taped to the outside of the San Francisco Federal Building. This is the moment—the spark of inspiration—when the AIDS Memorial Quilt was born.

When Cleve saw the patchwork of names, all written in their own unique style, on the side of the building he remarked that it looked like a quilt. Soon after he turned this idea into sewing sessions at friends and fellow activist houses—including the emerging politician Nancy Pelosi—into a novel form of community activism. Individual quilt panels are 3x6 feet, which is approximately the size of a coffin. Panels are grouped together in eights to create quilt blocks, which are 12x12 feet. In the earliest days of the AIDS Memorial Quilt, it became a form of remembrance and memorial. Funeral homes would often refuse people who died of AIDS, and sometimes the deceased’s family sadly chose to do no memorial. For many people in the gay community, this was the only way to remember loved ones who had been taken away in the prime of their lives.

Today, the AIDS Memorial Quilt is the largest community-based art project in the world. There are 6000 Quilt blocks representing 48,000 individual memorial panels to over 94,000 people. Many people remember the famous 1996 display of the Quilt on the National Mall in Washington DC, which was the last time the Quilt was displayed in its entirety. At the time there were only 3000 blocks. Displaying the entire Quilt today would be prohibitively complicated, as more than 20 acres of unobstructed land would be needed to fit all of the blocks.

The purpose of this exhibition is to recreate the early days of the AIDS Quilt, when it was a few activist friends meeting up in Nancy Pelosi’s living room to sew and talk and cry and laugh and remember loved ones who had died from AIDS. The gallery is divided up to create a series of roomlike spaces, so that when viewers walk through they feel as if they have been transported back to 1985 and are seeing first hand the AIDS Quilt coming together. The use of decorative framed artwork is meant to give the space a living-room quality, but look closer and each of these pieces have threads connecting it to the story of the AIDS Quilt. Also on display are actual activist artworks including comics, dolls, posters, and more for viewers to interact with to underscore the experience of living through the early days of the AIDS epidemic. Finally, a selection of AIDS Quilt blocks anchors the gallery space and show, reminding viewers how fundamental they are to the story of fighting the virus. When all these artworks are experienced as a whole, viewers can find a deeper connection to the story of the AIDS Memorial Quilt.

Aubrey Longley-Cook’s embroidery work contains multiple threads connecting it to the AIDS Memorial Quilt. As a queer artist and a fiber-based artist, he’s already had multiple exhibitions where his artwork was curated into a show which also featured AIDS Quilt blocks. Like many other gay men, including some who have made Quilt panels themselves, Aubrey was inspired to take up needlework after seeing his mother and other women in his family practice the artform. His pieces speak to time and place for the setting of this exhibition. The embroidery of a palm tree was chosen because of the palm’s abundance in San Francisco. Aubrey’s Hourglass series is meant to evoke the patterns of traditional Americana quilts. Embroidery framed on the wall has a nostalgic quality to it, and Aubrey’s work is meant to bring a homey feel to the gallery space.

Artwork by Robert Sherer often shocks people, but only once they dig deep into the meaning and intention behind his works. His drawings and paintings present bucolic scenes, but there is always some element—be it the medium, the process, the figure, or the story behind the work—that gives his work a sharp edge of artistic intention. For this exhibition, Robert’s bloodworks are on display. In this series the artist has literally drawn blood from friends and acquaintances—including both HIV+ and HIV- blood—and uses it as a medium for drawing and illustration. The scenes are straight out of a Victorian parlor with their precisely detailed flowers, bunnies, birds, and other rural paradise imagery. The red blood becomes a kind of antique ink which results in illustrations that could have come out of a dusty encyclopedia. The images are sweet and old-fashioned, which underscores the “Living Room” theme of this show.

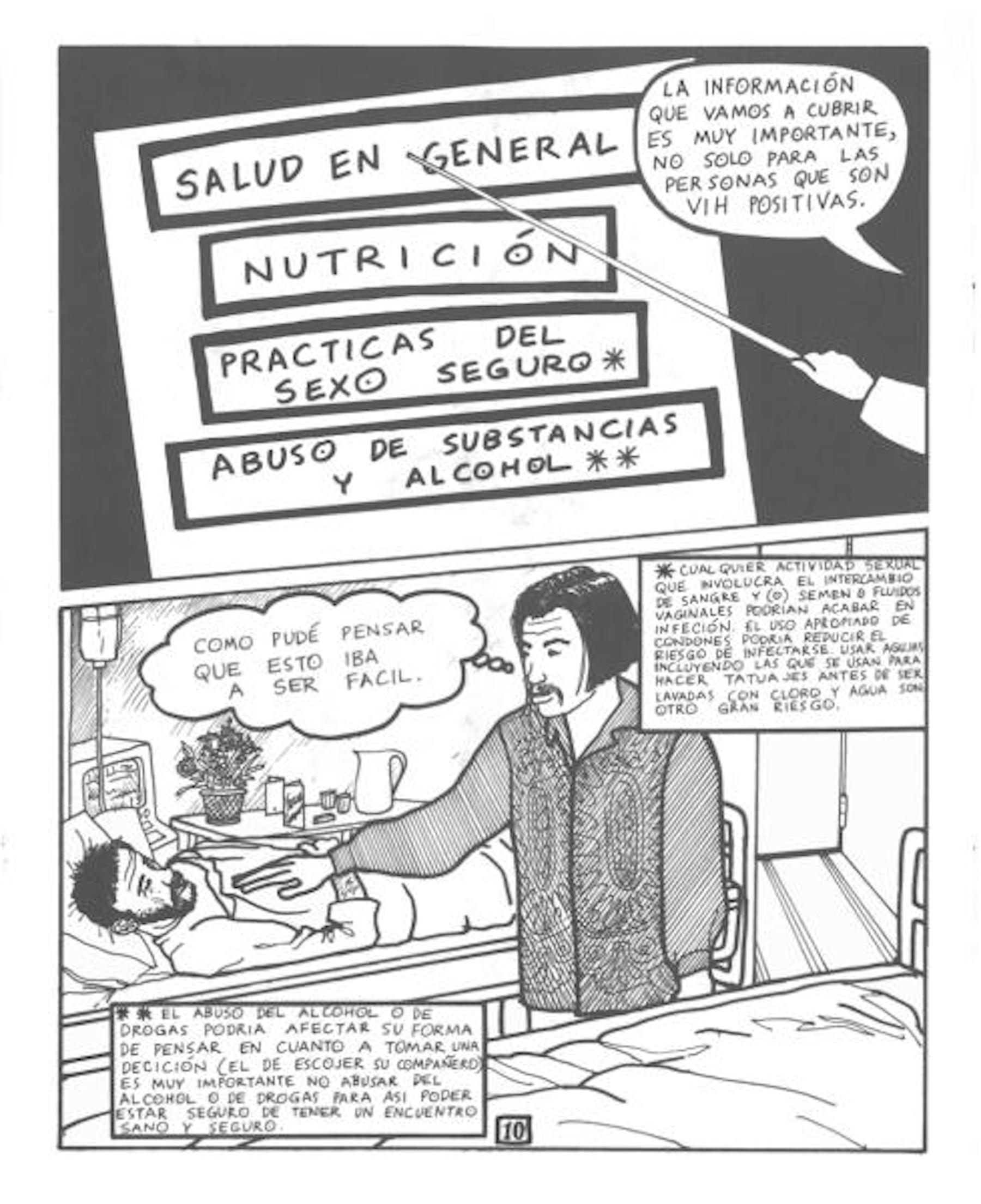

Activist artwork is central to the theme of this exhibition, which is why Joey Terrill’s work on Chicos Modernos fits perfectly into the narrative living room of the gallery space. In the days of the AIDS epidemic, before there was the viable three-drug cocktail (introduced in 1996) which reduced viral loads, many artists brought their skills to the forefront to fight the virus. In meetings, in living rooms, amongst friends and colleagues, people would share what they are working on to bring attention to the epidemic. This was the inspiration to have the “Touch” part of this exhibition which lets viewers physically interact with selected artwork. In order to place them in the world of the early days of AIDS activism, objects like Chicos Modernos recall that experience of sharing and seeing the pamphlets, posters, flyers, shirts, slogans, and more that other AIDS warriors were working on.

Chicos Modernos was a Spanish-written comic/‘zine teaching the importance of safe sex, aimed at the latino gay community and was sponsored by the LA County Department of Health. The booklets were passed out at bars and clubs, and then passed around between friends in the latino community. At the time, very little reliable, public information was available about how to prevent HIV; and even less of it was in Spanish. Chicos Modernos taught readers who were at risk for infection and how to take safety measures to stay healthy—with culturally-relevant comic storytelling elements. Chicos Modernos became not only an enjoyable comic, but an indirect health resource targeted to an underserved community which had lost thousands of individuals. With illustration panels that range from lighthearted to sexy to somber, Joey’s work helped save the lives of countless people at the height of the epidemic.

For three decades, Cynthia Davis has been on the board of AIDS Healthcare Foundation, the world’s largest HIV/AIDS healthcare organization providing care to more than 1.7 million patients worldwide. One of Cynthia’s passion projects became a popular program across the organization. Dolls of Hope started off as a way to create dolls to send to HIV/AIDS orphans in Africa, but has evolved into something much larger. Cynthia has led workshops with women recently diagnosed with HIV, and the experience of making dolls together helped these women open up and bond with each other. The Dolls of Hope come in many skin tones, and Cynthia encourages doll makers to express themselves and have fun styling their dolls. Much like many of the people who have made AIDS Quilts over the years, Cynthia (and most of her workshop participants) are not expert seamstresses. But with a needle, a little bit of thread, and plenty of creativity she has helped bring to life hundreds of dolls which have comforted children (and some adults) facing an HIV diagnosis.

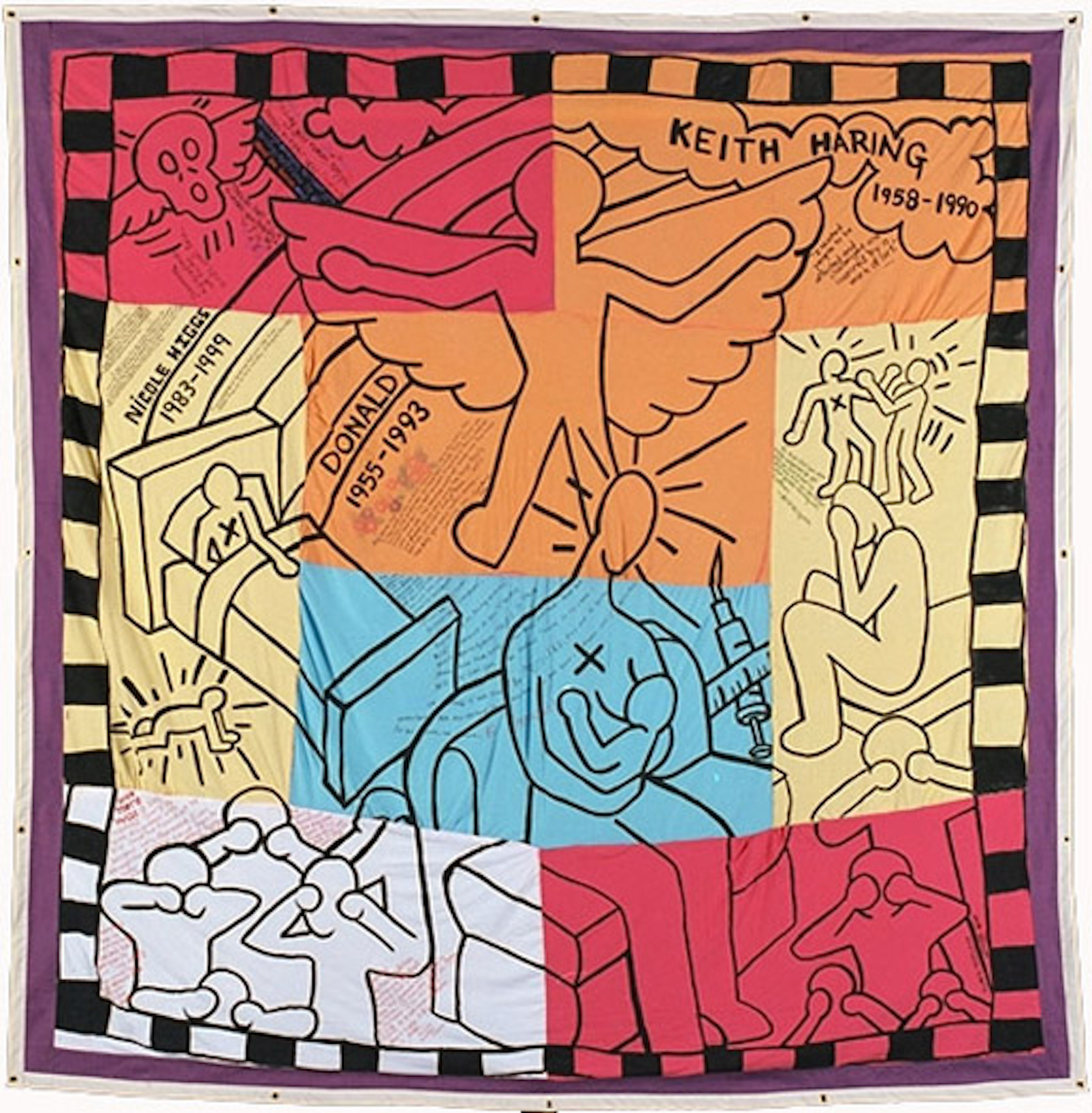

The AIDS Quilts chosen for this show each bring their own meaning. Two quilts were chosen because they would engage the local community—one quilt was made in honor of Atlanta Gay Men’s Chorus members who died of AIDS, and another quilt honors African Americans in entertainment who passed from the virus. One of the earliest quilts will be shown—made in the time when they sometimes only used first names, for fear of putting the full name of their friends out into the world. Finally, a quilt made by a Miami high school is perhaps the most beautiful of all the 6000 blocks—all eight panels come together to create a Keith Haring inspired motif that has a very arresting beauty.

The history of the AIDS Memorial Quilt shows the power of uniting people around a cause and using art to reach audiences in a deeper, soul-touching way to create positive change. For many of the names in the Quilt, this is the only remembrance of their lives and legacy. For viewers, the Quilt provides more than a memorial, but an educational tool about this dark part of our history, and the importance of reducing stigma and shame surrounding HIV. This exhibition shows what happens when all the threads are connected—of activists, of artists, of people using their creativity to create positive change in their lives and community—and how many people can come together to create a beautiful piece of art to bring light and love into dark times.

Matthew Terrell

Open Call Exhibition

© apexart 2023