KANTEN 観展 is a play on the Japanese kanji for perspective 観点 (kanten), and art exhibition 展覧会 (tenrankai)—coming together to indicate an exhibition of many perspectives. This exhibition reveals legacies of the Asia Pacific War from an array of viewpoints, demonstrating the ways in which the trauma of the past continues to have impact in the present.

Although often overshadowed in American history books, the Asia Pacific War comprised the largest theater of World War II—culminating in some of the most brutal battles, bombings, and atrocities of the 20th century. The contemporary artists presented in KANTEN 観展 each engage with the aftermath of Japanese imperialism, presenting audiences with a range of complex political and personal ramifications of wartime violence that may be overlooked by nationalized historical narratives.

At a moment when nationalism and neoliberal chauvinism are on the rise, their artwork re-evaluates what has been established as “history,” considering material and immaterial traces that have been passed down over time. The artworks in this exhibition confront the enduring logic of empire, exploring topics such as imperial subject-making, wartime displacement, and lingering ethnic discrimination, while also bringing attention to the role of the US in the postwar.

Japan’s development as a modern nation-state is a story of colonial expansion. Starting with territorial annexations of Hokkaido and Okinawa, the newly established Japanese state adopted colonial policies already in use by many western powers, spending the first half of the 20th century expanding the borders of their empire by taking over Taiwan, the Korean Peninsula, Sakhalin, the Liaodong Peninsula, the Northern Mariana Islands, the Marshall Islands, and Northeastern China. Japan reached the height of aggressive expansionism during the war, occupying many locales across the Pacific in its ambition to create the so-called “Greater East Asia Prosperity Sphere.”

This dark period is directly witnessed in the photographic work of Motoyuki Shitamichi. His ongoing series torii (2006-2012, 2017-Present) traces the shifting historical significance of the Shinto gates called torii that were inserted throughout Japan’s territorial conquests to demarcate the growing borders of the Empire. Shitamichi photographed torii that still exist outside of the boundaries of the modern-day Japanese nation, documenting remnants of imperial subject-making (kōminka) in which religion was used as an assimilation tool for colonial subjects. Each of Shitamichi’s photographs captures the way these stone monuments have been altered since the war—repurposed as infrastructural support in a residential neighborhood, disguised within a cemetery, or removed from view completely.

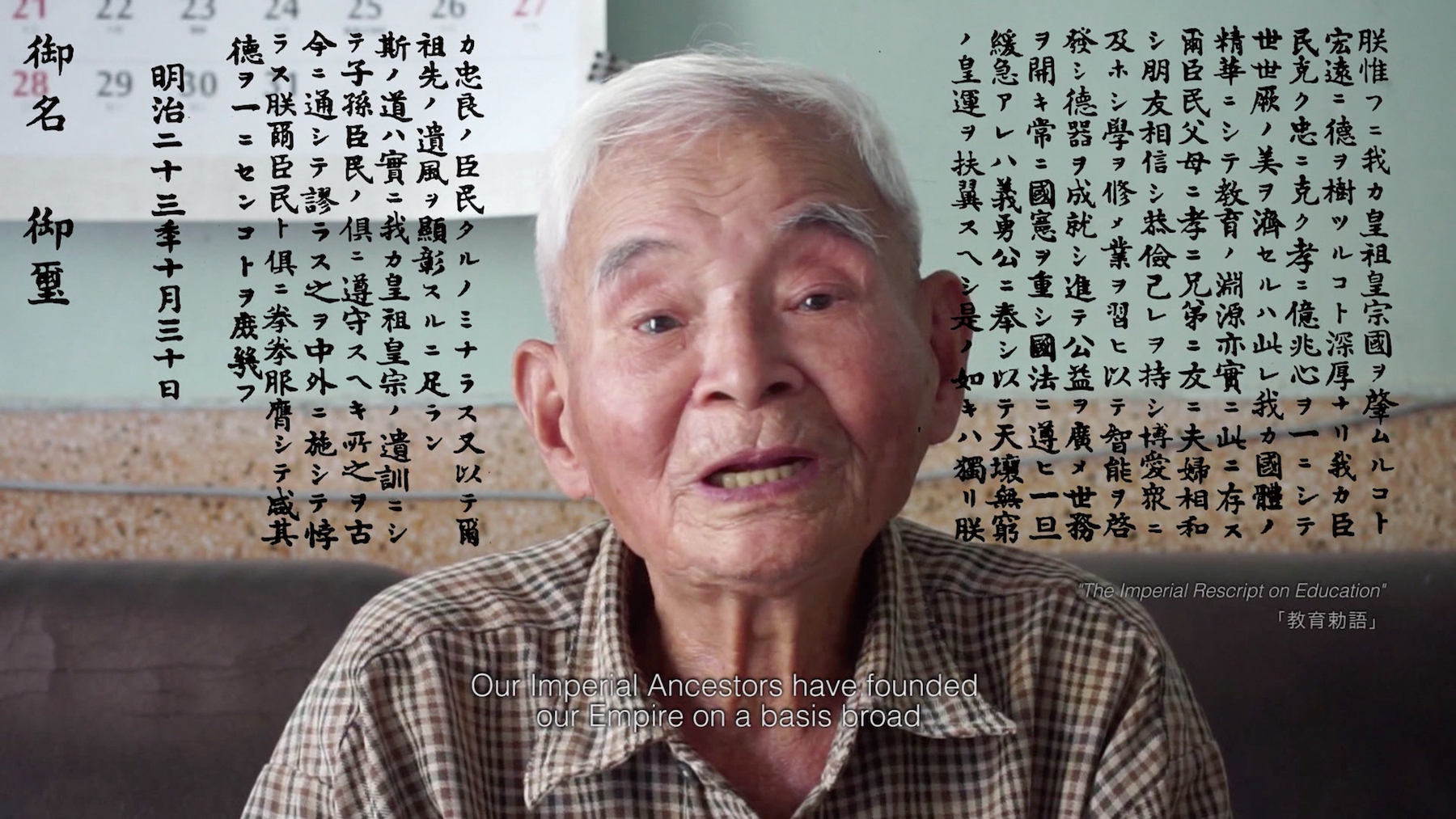

Forced assimilation policies of colonial subjects also included compulsory language education. Bontaro Dokuyama’s haunting video work My Anthem (2019) exposes these education policies directly by presenting interviews with a choir of Taiwanese elders who were schoolchildren during colonization. More than seven decades after the war, the deeply entrenched impacts of these assimilation methods are carried on in the memories of Taiwan’s elderly community. Viewers may be unsettled as an older gentleman recites the entirety of the Imperial Rescript on Education from memory, and the choir group dons school uniforms to sing the Japanese national anthem together as they did when they were children.

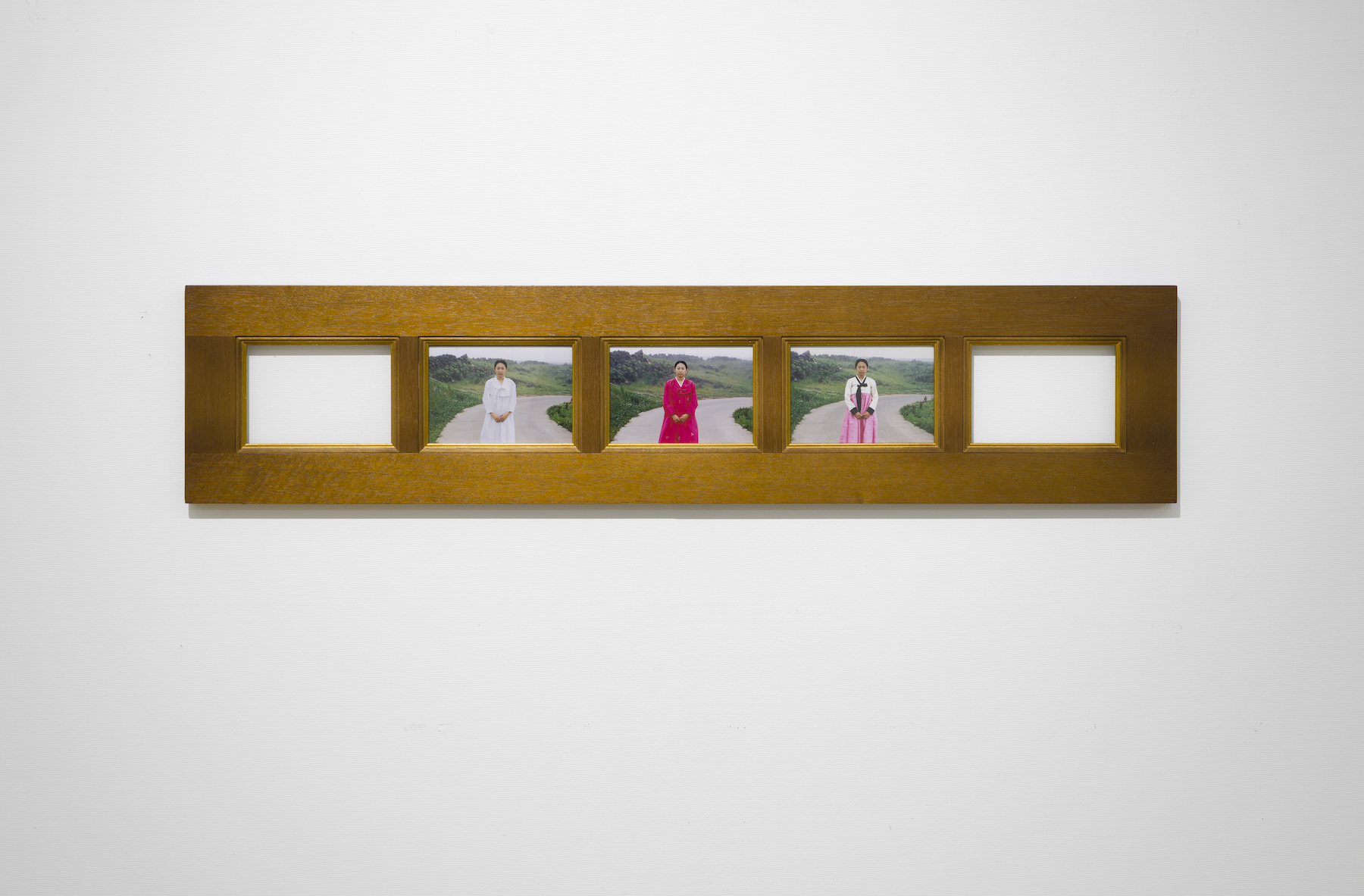

The systemic violence of the colonial period persists today in the form of intergenerational trauma passed down to the descendants of the subjugated. Haji Oh delves into the politics of memory and identity as a “Zainichi Korean,” or ethnically Korean resident of Japan. Oh’s work is not politically motivated, but rather an intimate exploration of the way trauma lives within and is passed down. Oh’s grandparents immigrated from Jeju Island in the 1930s but repressed stories from this time. Three Generations (2004) is a series of self-portraits in which Oh wears traditional Korean garments belonging to herself, her mother, and her grandmother. Through these photographs, Oh represents three generations of her family line, expressing the “unknowability” of the past and future of her family line as well as the unspoken, and perhaps unspeakable, memories that remain entombed in her ancestral home.

Soni Kum, also a third-generation Korean artist, takes a more direct political approach. She urgently engages with the echoes of the past, striving for reconciliation between the living and dead. Kum created the installation Colorblind: violence is contagious (2023) for this exhibition, emphasizing fragmented and concealed aspects of war trauma in a piece that unseals old wounds as well as unexpected opportunities for healing. Soni’s research-based art practice studies the division of Korea after the war, which led to countless Korean laborers in mainland Japan becoming a “stateless” population that faced prejudice as an ethnic minority in Japan. Inspired by the novelist Toni Morrison, Colorblind foregrounds the voices of the buried by exploring the fallout of colonial “liberation” and the brutality of the Korean War that followed. Kum’s work poignantly identifies the glaring similarities between the violence faced by Koreans of the 20th century and US policies towards Black communities in America.

Furthering Kum’s approach to the underside of history are Kyun-Chome and Taro Furukata. The artist duo Kyun-Chome, made up of Eri Honma and Nabuchi, produced a feature-length art film Making a Perfect Donut (2019) surveying the geopolitical position of Okinawa, Japan’s southernmost island prefecture. Housing 75% of US military bases in Japan, Okinawa is considered the cornerstone of American military power in the Pacific. The premise of the film is the artists’ proposal to make a “perfect donut” by combining a traditional Okinawan sātā andagi donut and an American donut through the military fence. The film documents the artists’ conversations with local residents about their bizarre idea, weaving together transpacific, geopolitical dynamics with the realities of daily life to show the vast complexity of Okinawa’s dual-colonization. Ultimately, Kyun-Chome’s quippy, unpretentious film highlights Japan’s prolonged complicity with US militarism.

Born and based in Hiroshima, Taro Furukata scrutinizes the paradox of US-Japan relations and propaganda in the postwar. The Perfect Hug (2018) unpacks the messaging of the renowned Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, which was constructed to memorialize the devastation of the atomic bombing of the city by US forces while also venerating Hiroshima’s emblematic commitment to future peace. Furukata’s video installation informs viewers that the park’s design is eerily similar to unrealized architectural plans for the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere Memorial Hall.” Comparing the park designs with the widely publicized image of Barack Obama’s embrace with an atomic bomb survivor in 2016, Furukata demonstrates that both “perfectly” center the violence of the past in blithely reconciliatory ways, a form of historical revision that deliberately obscures the past.

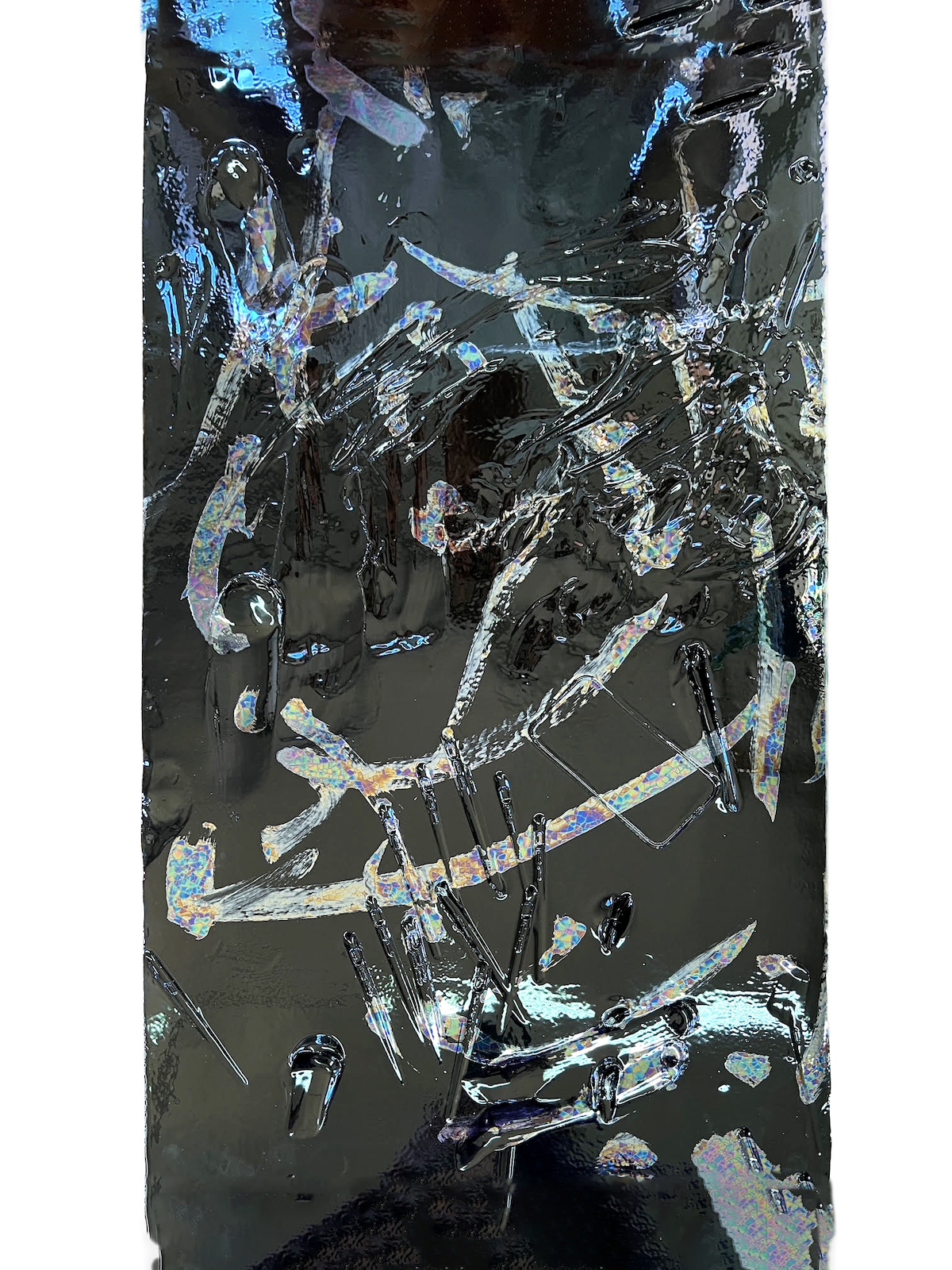

With this exhibition being held in the US, it is vital to recognize that the war also had extreme ramifications across the Pacific—following the Pearl Harbor attack, Japanese residents of the west coast of the US were forcibly removed from their homes and relocated to concentration camps further inland. American artist Ken Okiishi grapples with the aftermath of displacement policies in Untitled (2022). Okiishi’s family held a longstanding transnational presence between Hiroshima and Hawai’i in the years before the war. Legend has it that after the bombing his grandfather dumped all traces of his family’s Japanese ancestry into Māmala Bay to avoid arrest. Generations later, the artist deliberates on the yet “unconfirmed relations” that he holds with this history in a process he has called “illiterate calligraphy.” Created from glazed terracotta, Untitled evokes the altered possibilities of identity that Okiishi has been able to perform in his everyday life as a Japanese American.

The final component of this exhibition is a selection of imperial war postcards from the East Asia Image Collection at Lafayette College. Widely published and circulated in Japan and its territories during the war, postcards played a vital role in perpetuating intra-imperial propaganda of its notions of Pan-Asian “co-prosperity” at a grassroots level. Particularly disturbing is the proliferation of children in this collection of postcards—Japanese children posed as future imperialists, as well as children of occupied territories being cared for by Japanese soldiers. Domestic, familial imagery may have made the nation’s aggressive warfare more palatable for laypeople. They may have imagined Japan as the filial parent of the region, benevolently paving the road to Asian modernity. By juxtaposing the works of contemporary artists with historical materials that showcase empire-mandated perspectives of the era, this exhibition aims to reveal the limits of memory, narrative, and testimony.

Art has the uniquely provocative power to express the inexpressible, activate nuanced conversations, and bring forth parallels that may remain hidden otherwise. KANTEN 館展 confronts the limits of history, bringing together artworks that both construct and dismantle our understanding of the Asia Pacific War and its fallout. This exhibition broadens the resistance against the enduring aversion towards discussing and informing future generations about histories that are damning, reprehensible, and unpatriotic—the dark side of history that those in power often benefit from forgetting.

The curator would like to express gratitude to the artists, many of whom take on great risks in their artmaking. She also thanks all who have supported her research for this exhibition.

Eimi Tagore-Erwin

Open Call Exhibition

© apexart 2023