Nearly 7,000 migrant workers have died thus far in preparation for Qatar’s 2022 FIFA World Cup, and the recent pandemic has left many more stranded, unpaid, and neglected. This is just one example of how the kafala sponsorship system creates a migrant worker crisis in the Gulf Cooperation Council nations. Predatory recruiters lure workers from impoverished nations across Africa and Asia into leaving their families, only to endure low wages, unconscionably long shifts, scorching heat, inhumane living conditions, and abuse. Some employers illegally confiscate worker passports, or trade their visas to the highest bidder. Expatriate workers who are employed through the kafala system cannot transfer jobs, obtain a driver’s license, rent an apartment, open a bank account, or leave the country without the sponsor’s consent.

This exhibition surveys art and creative activism exposing this exploitative system and calls for its reform. It consists of illustrations for investigative journalism, designs for activism by the Gulf Labor Artist Coalition, and photography – both candid and staged – focusing a lens on those who migrate to oil-rich nations with the false hopes of more lucrative work.

Visitors enter and exit the exhibition with a view of Hanna Barczyk’s illustration Human Trafficking Maze. This piece inspired the gallery’s labyrinthine floor plan, which is broken into tight spaces to replicate the claustrophobic dormitories guest workers inhabit and the crowded buses that carry them to worksites.

Ryan Inzana’s digital illustration for The Nation’s article “Why Are Thousands of Malagasy Women Being Trafficked to Abusive Jobs in the Middle East?” visually narrates the widespread trauma experienced by those who live and work in the homes of their sponsors. Many domestic workers receive inadequate food, poor medical care, and little or no leave. They often face physical, psychological, and sexual abuse. In even bleaker instances, there have been numerous accounts of suicide among domestic workers, and of their homicide at the hands of their sponsors.

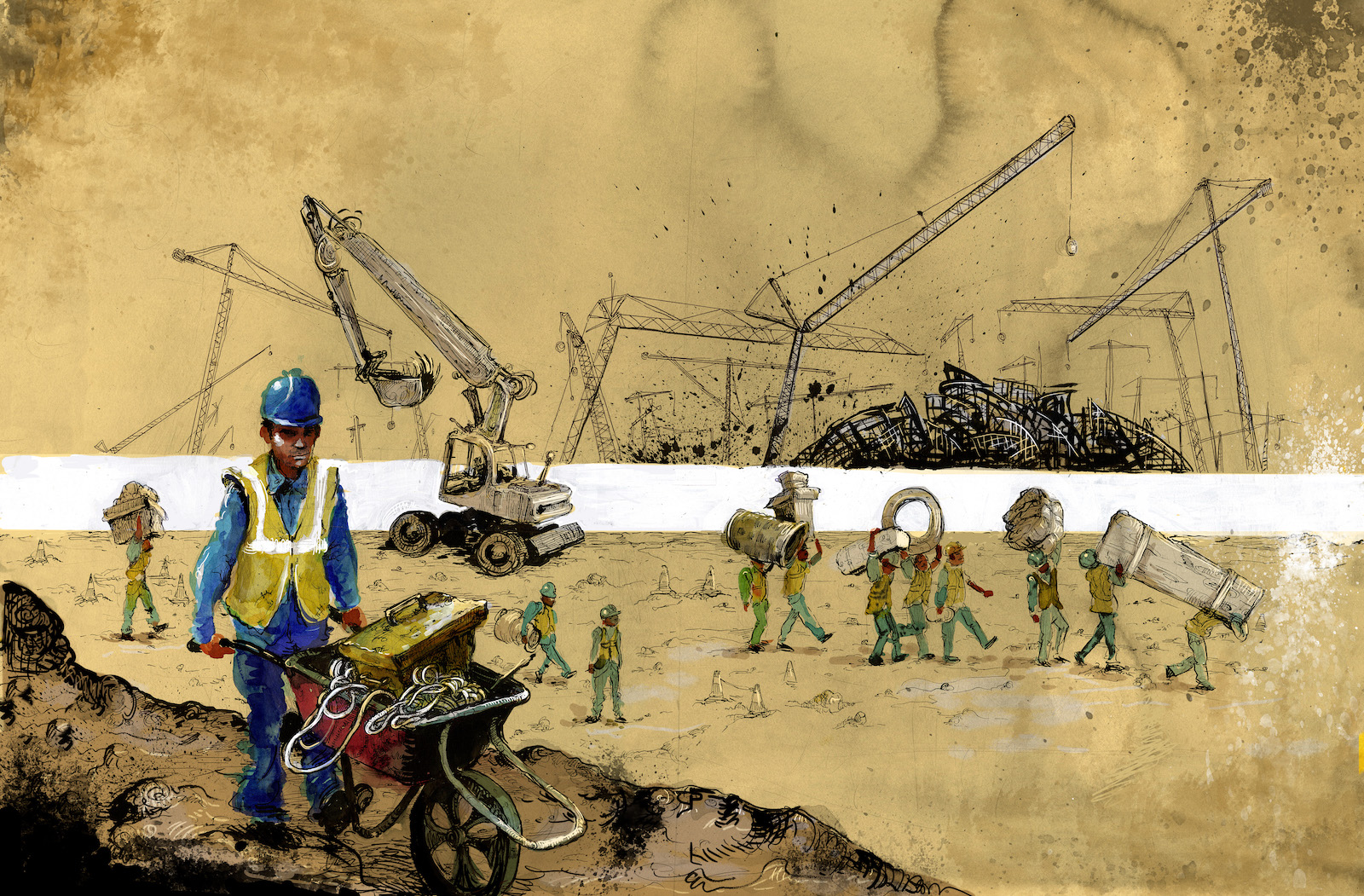

Molly Crabapple’s ink and watercolor drawings and written exposé reveal the plight of the construction workers building the Louvre in Abu Dhabi’s burgeoning cultural center of Saadiyat Island. For her feature in VICE titled “The Slaves of Happiness Island,” Molly snuck onto construction sites to avoid government handlers. There, she conducted anonymous interviews with men working seven days a week in sweltering heat for as little as $176 a month, all while accruing recruitment fees that take years to pay off. One worker told her, “My message to the head of the Louvre would be to come and see how we are living here.” Another added, “Hell is better than here.” Efforts among workers to unionize or protest their conditions have been met with police brutality, arrest, and deportation. Despite Crabapple’s requests for comment, The Guggenheim was unwilling to provide a statement due to erroneous assertions that Crabapple was part of the Gulf Labor Artist Coalition.

A group of artists, writers, architects, and curators known as the Gulf Labor Artist Coalition have organized creative interventions to advocate for the rights of the migrant workers constructing educational and cultural institutions in Abu Dhabi, including the New York University campus, Performing Arts Center, Sheikh Zayed National Museum, The Guggenheim, and Louvre Museum.

Some Gulf Labor member artists have helped lead the movement, and have created stand-alone works critiquing the kafala system. Noah Fischer of the Global Ultra Luxury Faction (G.U.L.F.) began organizing during Occupy Wall Street (O.W.S.) Protests of 2011, where he was instrumental in forming Occupy Museums. Along with other activists from Liberty Square (a.k.a. Zuccotti Park) Noah supported Gulf Labor with sit-ins, leaflet drops, and direct actions in the rotunda of the Guggenheim, along with projections upon its façade by the O.W.S. Illuminator. In Noah’s graphic novel-style watercolor and ink series The Giant Pit, he explores the absurdity of labor abuse within the contemporary visual arts. Set in a dystopian future on Saadiyat Island, the story follows an aging art worker into a nightmarish scenario in which the Guggenheim family’s nineteenth century fortune in mineral extraction is colorfully elucidated at his expense.

Other creative actions by the Gulf Labor Artist Coalition were done in coordination across the member cohort. 52 Weeks is the title of their year-long campaign that began in October 2013. Each week, members contributed works of art, text, and direct action exposing the unjust living and working conditions of migrant laborers. Frequently, artists chose to design posters, which were made widely available through printable files. The projects below are selected from 52 Weeks.

Week 7: Gregory Sholette and Matt Greco collaborated on the creation of 3D-printed miniatures of the prison-like residential quarters for Saadiyat Island workers. In a guerilla action known as “shop dropping,” they covertly placed the packaged collectibles on merchandise shelves in The Guggenheim’s New York City gift store for unsuspecting shoppers to discover.

Week 14: Pedro Lasch released a limited-edition poster titled Of Saadiyat’s Rectangles & Curves, or Santiago Sierra’s One Sheikh, Two Museum Directors, Three Curators, One University President, Two Architects, and One Artist Remunerated to Sleep for 30 Days in 13 x 14 foot Windowless Room with Shared Bathroom and No Door. Pedro designed this poster for his ongoing series ART BIENNIALS & OTHER GLOBAL DISASTERS. In the poster, Pedro contrasts the enormous footprints of the institutions built in Abu Dhabi and in the Venice Biennale’s international pavilions, with the standard 182-square-foot bedrooms shared by ten migrant construction workers in Saadiyat Island.

Week 28: Todd Ayoung and Jelena Stojanović (a.k.a. the Alien Abduction Collective) submitted the diptych poster A Paradox on Citizenry and Creativity. The digitally altered image of a janitor mopping the floor of a Chelsea gallery draws connections between the immigrant labor that is behind both the construction of global art museums, and service work in New York City. Both sets of laborers maintain the “hygiene” of the privileged white cube of creative capital. Their specific social, political and economic conditions may be different in some ways, but they are both wage slaves of imperialism, colonialism, private property, and of international capitalist markets.

Week 29: Mariam Ghani’s And We Wondered overlays text from interviews with Gulf Air cabin crew members atop a photo of worker transportation shuttles during their pre-dawn operations. In their testimonies, the flight attendants ponder if new recruits waiting to board flights to construction jobs in the Gulf are aware of the “devil’s bargain” they signed up for.

Week 30: Jaret Vadera’s poster BLUE SKIES, WHITE WALLS, BROWN BODIES deftly transposes its title into a minimalist landscape. Jaret uses the interplay between text and color to poetically reveal the underlying relationships between violence and aesthetic hierarchies at play in architecture, art, and labor in the Gulf.

Week 49: Dread Scott’s Your Elite Status is Guaranteed satirically appropriates a promotional still from the film The Little Colonel, in which an affluent white child (Shirley Temple) befriends a Black servant (Bill “Bojangles” Robinson) during the Jim Crow era. Parodying the myth of the “happy servant,” Dread subversively includes the logo and taglines of Tourism Development & Investment Company -- Abu Dhabi’s flagship project -- at the poster’s bottom.

The group’s work culminated at the 2015 Venice Biennale with a series of panel discussions on the nexus of art, labor, and capital in the Emirates, a celebratory pageant performance, and the launch of their book The Gulf: High Culture/Hard Labor edited by NYU Professor Dr. Andrew Ross. The Emirati government banned several members, including Andrew, from entering the country due to their association with the group.

Photographs in the exhibition provide a contrast between despair and resilience. Norwegian photojournalist Jonas Bendiksen’s unscripted empathy-invoking photos expose the stark realities of working abroad under kafala. He documents the grim reality of migrant workers’ lives in the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, and Qatar in his photographic reportage series “Far From Home,” for National Geographic. Additionally, his journey to the Philippines captures a glimpse of the recruiting agencies, training facilities, and family members that workers leave behind. This series reveals the banality, inequality, and invisibility of those who sacrifice everything to send a small pittance to relatives.

Expatriates comprise nearly 85% of the Arabian Gulf’s population yet are virtually invisible in pop culture, advertising, and social media. The Doha Fashion Fridays joint Instagram project humanizes, honors, and celebrates the individuality, creativity, and style of foreign workers in Qatar. Street portraits by Sudanese artist Khalid Al Baih and Indian photographer Aparna Jayakumar showcase guest workers’ sartorial choices on their only day off. Aparna explains, “It’s beyond fashion because the point of this project is to give visibility to people who go unnoticed otherwise in real life. How you dress is such an expression of who you are. But for six days a week, they’re not allowed to express themselves, so they go the extra mile on the day they can.”

With Khalid’s blessing, in February 2020, I began visiting the corniche in Kuwait City to photograph and interview expatriates from India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Egypt, and The Philippines. I asked them about their lives in Kuwait and what inspired their outfits, and later emailed them their edited portraits. While the Covid pandemic interrupted this practice, it is my hope this exhibition reignites this project.

Several reforms to the kafala laws have been passed throughout the Gulf region. However, human rights organizations believe these laws are inadequate and are not enforced. Foreign workers are still vulnerable to wage theft and confiscation of their work permits, while employers rarely face any repercussions. To address this crisis, it is crucial to keep talking about it, and hold its beneficiaries accountable.

Clark Clark

Open Call Exhibition

© apexart 2022