California is home to the largest population of individuals of Asian descent in the U.S. From the galleon ships that brought sailors to the Americas from the Philippines in the 16th century to the contract laborers who arrived from China in the 1850s, many groups from Asia immigrated to escape hardship, war, or colonization, only to endure policies of exclusion, indentured servitude, racist policies, and negative stereotyping in their new home. Today, violence and prejudice continue in the form of scapegoating around the COVID-19 pandemic.

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, immigration policies in the U.S. fluctuated in parallel to racialized fear and anxiety among political leaders and the majority-white public. It was not until 1965 that national origins quotas were abolished through the Immigration and Nationality Act, also known as the Hart-Cellar Act, sparking a new wave of mass immigrations. Prior to 1965, such influxes primarily came from Europe. Post-1965, the majority of new immigrants arrived from Latin America and Asia.

Although highly skilled professionals could now settle in the U.S. based on new immigration preference categories, many came ashore to flee communism, war, repressive governments, and economic hardship. For example, immigration skyrocketed from Taiwan and Hong Kong after the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre when the Chinese army targeted pro-democracy activists. Conflicts such as the Vietnam War also had a heavy impact. As the 20th century wore on, more individuals and families from Vietnam, Laos, Pakistan, Bangladesh, India, and Cambodia immigrated to the U.S. The representation of economic and education level across immigrants proved to be equally as vast as the spectrum of motives for immigrating to the U.S. Asians now represented high median annual earnings but also high poverty rates. And while the Asian American population grew over the decades, old prejudices and violence wielded against these communities continued.

In the 1960s, the tide began to turn along with a changing social and political consciousness across the U.S. and world. Inspired by civil rights, antiwar, and Black Power movements, a body of Asian Americans began to rally for new political visibility. As cultural historian Daryl Maeda wrote, they “sought to achieve radical social change by building interracial coalitions and transnational solidarities.”1 The Asian American Political Alliance, which formed in May 1968 at University of California, Berkeley, first publicly used the term “Asian American,” which came to define larger pan-Asian social movements from the 1960s to 1980s. Other alliances emerged at this juncture: Asians joined forces with Native American, Chicano, and Black students at San Francisco State University at the Third World Liberation Front in 1968, which fought for curriculum and admissions reform across campuses.

This advocacy and call for social change also appeared through the work of visual and performing artists. In the Bay Area, artists such as Carlos Villa approached their art-making through multiple non-Western viewpoints and through activism and teaching. Other well-known artists witnessed how racial injustices impacted Asians and communities of color while creating remarkable bodies of work. They include Ruth Asawa, Bernice Bing, Chiura Obata, Kay Sekimachi, Leo Valledor, and Jade Snow Wong.

The coalescence of art with social or personal consciousness continues in the Bay Area with Ctrl+Alt+Yellow, an exhibition that convenes local contemporary artists with Asian lineage who imagine alternative modes of existence and relation.

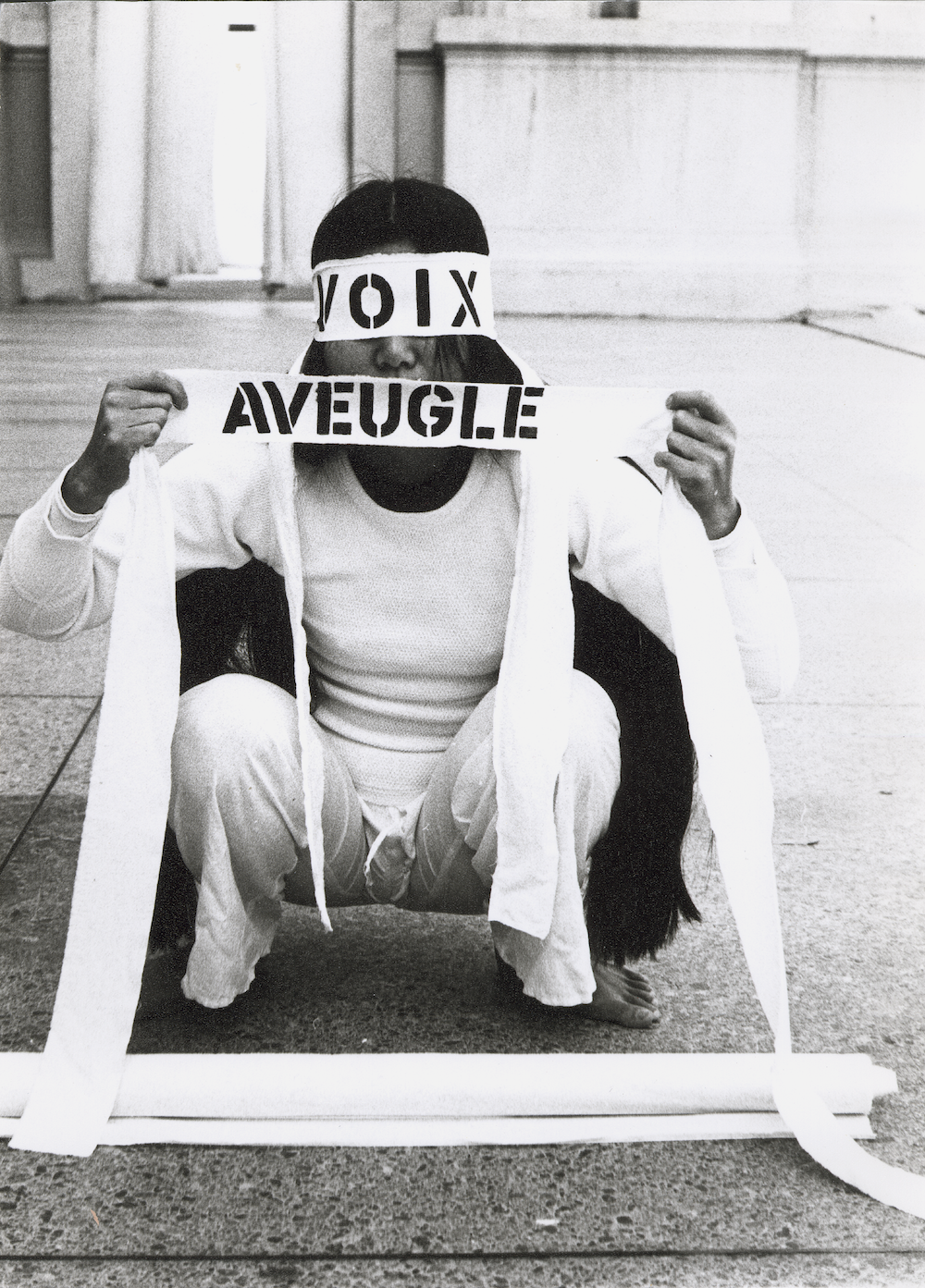

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha began her studies at University of California, Berkeley in 1969, a pivotal time when universities were broadening the perspectives represented in subject matter and campus activism made headlines. As an artist also of the written word, she employed language and mythology to examine the discomfort of one’s own “foreign” language(s). Born in Busan, Cha emigrated to the U.S. to escape repressive military rule in Korea, becoming fluent in English and French.

Much of Cha’s work evades translation or direct contextualization. By standing firmly—and sometimes more loosely—in a language, performances like Aveugle voix refuse to dilute, simplify, or translate their intended meanings. The banner Cha unfurls in Aveugle voix can be read in two directions: “WORDS FAIL ME SANS MOT SANS VOIX AVEUGLE GESTE.”

“Aveugle voix” is perhaps a deliberate reversal of voix aveugle, or “blind voice,” which would follow the expected grammatical rules of French. To translate the title Aveugle voix would mute the nuances of the performance, which itself is a meditation on navigating between cultures and histories. From the choppy language of the banner and Cha’s face coverings, the specter of female martyrs emerge. Just after the publication of her key work Dictée, Cha became a victim of rape and murder at the age of 31—a violent end rarely discussed at length alongside her artistic output.

In another exploration of language and access, Love Letter by Zihan Jia explores Nüshu—perhaps the only writing system created and used exclusively by women that reached its peak use during the Qing dynasty (1644-1912). In these photographs, the artist transforms a love poem by Shangguan Wan’er (a female official, poet, and imperial concubine of the Tang Dynasty) from Nüshu into her own bodily form in athletic wear surrounded by equipment most often associated with men’s sports. Both Cha and Jia’s works point to how language and the refusal of translation can be tactically applied against oppressors or social norms. These internal codes allow for new types of communication to emerge, transcending immediate legibility or alternatively suggesting multiple modes of legibility.

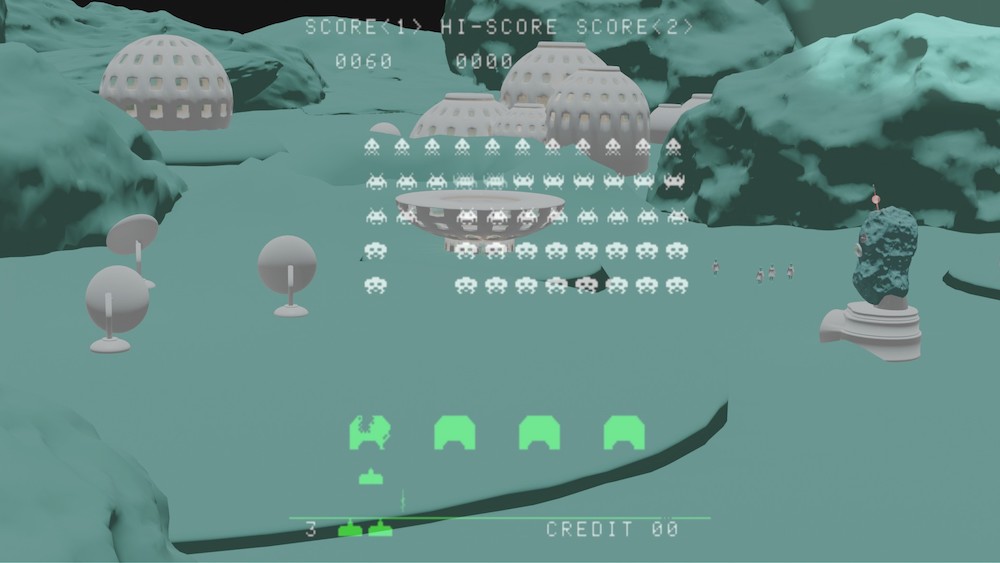

Genevieve Quick uses a more playful, fantastical narrative in her video work Planet Celadon: Operation Completed. The artist evokes traditional celadon, a green ceramic glaze widespread throughout eastern Asia, to examine Asian diasporic identity. Applying a literal interpretation of the term “alien,” the protagonists of the film are bright seafoam green-colored figures who communicate via aeronautical gestures, computer graphic symbols, early computer games, and Google Earth. When these Celadonians land in Asia via the Rockette Ship, they complete their “interplanetary migration.” Here futurism blends with tradition, and alien with earthbound.

On a more earthly level, For You Performance Collective’s The Great AAPI Elder Print-Off connects Bay Area AAPI elders with artists during a period of extreme isolation. Erika Chong Shuch and Ryan Tacata, whose collective centers around a spirit of gift-giving, focused their creative outlets in spring 2021 to collaborate with the organization Little Brothers – Friends of the Elderly (LBFE). Earlier in the Covid-19 pandemic and with the rise of anti-Asian racism, For You explored a new possibility for connection by pairing artists working in social practice and performance with AAPI elders associated with LBFE and other organizations. Following conversations between each duo, artists created a homemade activist poster to amplify each elder’s voice. Writer Rebecca Solnit points to the mutual aid and “brief paradise” that appears during times of crisis or disaster when the “shackles of conventional belief and role fall away and the possibilities open up.”2 These posters, which demonstrate glimmers of mutual benefit in a time of crisis, are available online at www.foryou.productions for anyone to print and post.

Treadling a Lost Journey, an interactive kinetic installation by Taro Hattori, acknowledges loss and transmutes the personal experiences of many into song. Visitors are invited to operate a treadle sewing machine, which sets wooden wheels into motion and activates projected video and sound. The songs, compiled by the artist from a range of participants both within and outside the local AAPI community, emanate from inside the sewing machine, describing loss and longing. As a child, Hattori often sat at his mother’s sewing machine, with its leather belt disengaged, imagining travel to fictitious places through light and shadow. The artist’s dream apparatus and family keepsake here serves as a conduit for childhood memory, loss, preservation, and transmutation.

The treadle also alludes to the strong link between Chinese immigrants to the garment industry in late 19th century American cities. The California Garment Factory—founded in 1915 just blocks away from the exhibition venue—reached its peak production in the mid-20th century, when the business grew to over 100 sewing machine operators. Overall workforce numbers shrank and grew with the implementation and repeal of various Chinese exclusion acts. It especially grew with the Immigration Act of 1965; by the 1980s, there were around 600 Chinese-owned factories in the Los Angeles area and Bay Area. With the globalization of the garment industry outsourcing production in favor of cheap labor, the industry in the Bay Area shrank dramatically in the late 20th century. However, the garment industry stands as a prime example of how immigrants carved a niche for themselves and grew to be both self-sufficient and a contributing force to the economy.

Through Kutty the Youngest One, Vasudhaa Narayanan connects present-day recollection and imagination as it relates to family, self, origin, and culture. In this video and photographic work, she holds conversations with her grandparents after their passing. It is a meditation on language, what she did not and now hopes to know about her grandparents, and the dim yet stark space between knowing and not knowing. As an adult, her questions to her grandparents in this narrative are many: “What was your favorite sari to wear?” “Why did you give me my name?”

Through media spanning video, installation, print, and photography, these six contemporary artists conceptualize Asian American identity through humor, imagination, movement, and intergenerational dialogue. In each their own way, they employ radical modes of narration, exemplifying how communities and individuals can take charge of their own stories to re-construct their own understanding of the past, the realities of the present, and future potentialities.

Janet Oh

Open Call Exhibition

© apexart 2021

1. Daryl Joji Maeda, “Introduction,” Rethinking the Asian American Movement, ed. Daryl Maeda (New York: Routledge, 2012), 1.

2. Rebecca Solnit, A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster (New York: Penguin, 2010), 97.