With the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, pundits rejoiced in the dawn of a new era, a world without walls. Instead, walls now permeate our world with 33 nation-states constructing them. Walls now separate Spain from Morocco (in the exclaves of Ceuta and Melilla), India from Bangladesh, Saudi Arabia from Yemen, Botswana from Mozambique, and the United States from Mexico. Many countries, including the United States, view border walls as a key element in their wars on terror, undocumented immigration, and smuggling. These walls are the centerpiece of policies aimed at increased militarization and the reconfiguration of rights and citizenship at borders. Their construction is part of a border security industry that includes collaborations between the public sector and multinational corporations. Even though border walls are a strategic reaffirmation of state sovereignty, states build them with minimal public input on their necessity, location, and design. Concrete walls, metal fences, and concertina wire speak to the overwhelmingly militaristic logic that guides the prevailing approach to borders. More specifically, in the United States, mainstream media, through its reporting and circulation of images, fuels the public’s articulation of borders as war zones. Mexican-American residents of border communities, border artists, human rights advocates, leaders of Native American groups, and environmental organizations contest this onslaught of government and corporate domination as well as the mass mediated spectacular. This contestation is a story rarely told and a media imaginary rarely re-imagined.

This bilingual (English and Spanish) group exhibition brings together work by artists, activists, architects, and other public intellectuals who have created alternative designs for or fought the construction of the United States - Mexico border wall. The major questions that this exhibition addresses include: How can we reassert a more populist notion of sovereignty by re-imagining borders? What is the role of art and architecture in providing a bulwark against the erosion of democracy that border walls materialize?

"1,950 mile-long open wound

dividing a pueblo, a culture

running down the length of my body,

staking fence rods in my flesh,

splits me splits me

me raja me raja"

–Gloria Anzaldúa, La Frontera/Borderlands 1987

Raja (split) encompasses how borders not only divide but also scar and wound both the landscape and people (namely, Mexican-American citizens residing in the borderlands) it also describes how the border wall affects borderland culture on the United States side. The painter Celeste De Luna shows the border wall as it cuts through the in-between spaces of border culture while mapping this "tearing" onto border residents’ subjectivities and bodies. In Anchor Baby, De Luna represents a pregnant women’s torso and upper body as the dividing line between the United States and Mexico, with picket fencing and barbed wire entrapping and severing her bare breasts and limbs. Within her body is a mature fetus encircled by an anchor calling attention to how childbirth is rendered a crime within the militarized framework of the border wall, antiimmigration discourse, and presidential candidates wanting to end birthright citizenship.

A series of ethnographic photographs invite contemplation about how the border wall splits people, communities, and nature preserves in the United States. A photograph from a community museum and park, Pedestrian Trail (Miguel Díaz Barriga and Margaret Dorsey), centers the viewer’s attention on a sign pointing to hiking trails in South Texas sliced by the wall. In a place where 90% of residents are Latina/o, and the poverty rate is among the highest in the nation, such action slices more than a park. The wall literally cuts into family life as illustrated in a photograph of metal pylons from the border wall rising behind the backyard of a house in Granjeno, Texas.

The art of Alfred J. Quiroz draws attention to the theological and existential aspects of border crossings, including miracles and deaths. The exhibition includes three border milagros: Mano por Centavo, Brazo de Trabajo, and Sinagua from his binational Parade of Humanity project in which he attached sixteen giant metallic sculptures to the Arizona border wall. The three milagros (icons that reference miraculous events) featured at apexart draw inspiration from religious amulets popular in Mexican vernacular Catholicism, and also highlight the deathly nature of border crossers’ experiences, as people regularly die in the desert from dehydration. Anthropologists also locate the wall in relation to the experiences of migrants, the transformation of the landscape into killing fields, and, in subtler ways, the reshaping of border subjectivities.

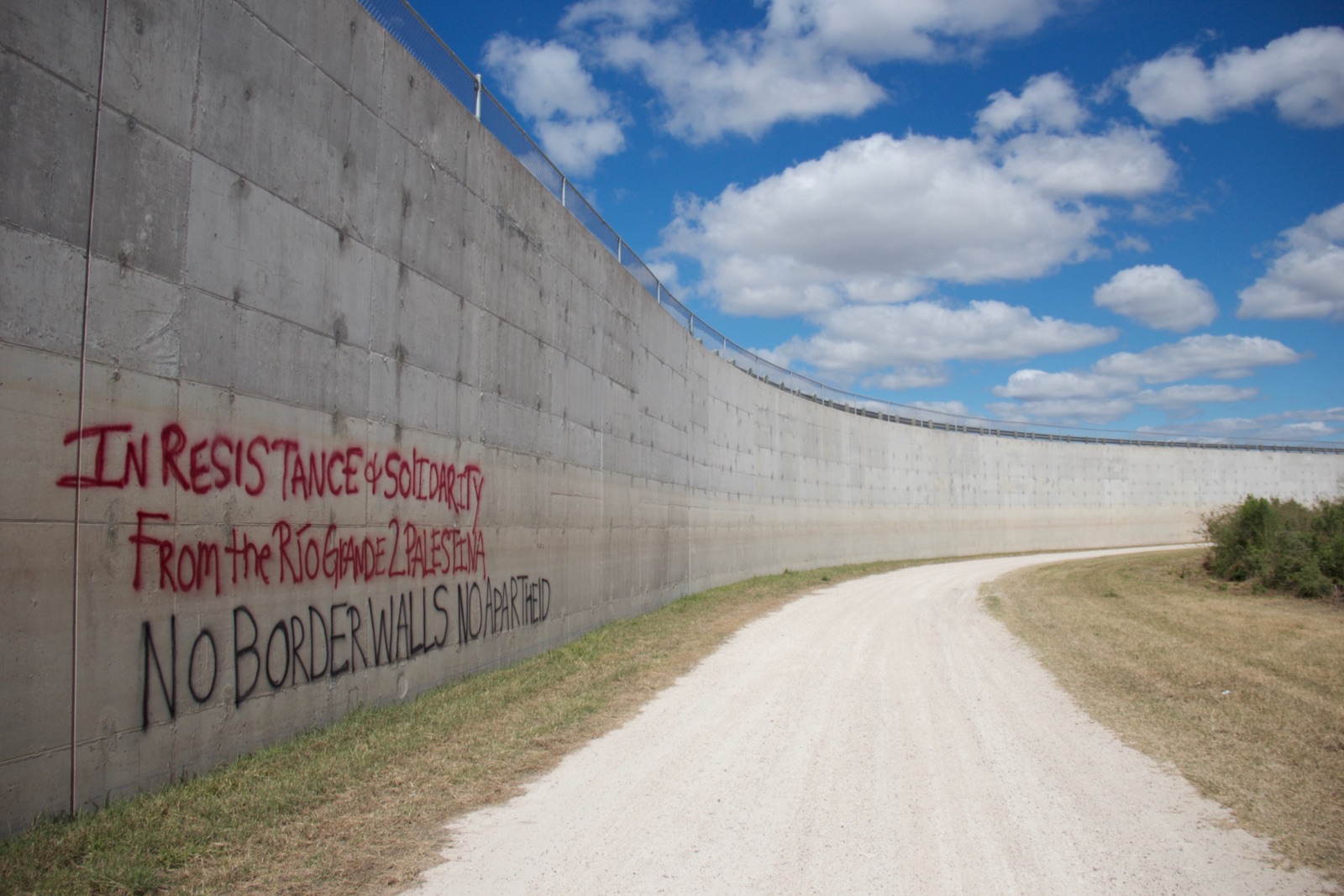

Photographs provided by Jason De León feature the border crossing experience from the perspective of migrants themselves, and Carolina Rocha’s digital recordings voice migrants’ fear as they cross the international boundary, border wall, and interior checkpoints. Gilberto Rosas and Randall McGuire’s photographs capture anti-militarization graffiti and the paradoxes of border life, focusing on the wall as state violence. Lupe Flores documents United States border residents’ unease with their community’s militarization in his photograph Abrazos No Balazos/Hugs not Slugs in which adolescents hug in front of the border wall. The improvised nature of the graffiti suggests the ephemeral yet embodied and visceral nature of their disappointment with the immense concrete wall that stands in their backyard. Alejandro Lugo interprets late twentieth century borderlands culture through a larger history of conquest, and his photographs of the border wall and the Statue of Liberty are symbolic gestures towards such conquest.

Architects reimagine the border wall’s potential as a generative site of binational cooperation. An installation in the exhibition features architects Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello’s vision for repurposing the wall’s concrete and metal into hike and bike trails along the border, solar panels that generate electricity for residents, and water collection stations (a statement on the deaths from dehydration). Another architectural redesign is James Brown’s plan for a "friendlier" Friendship Park. Brown’s proposal restores cross-border human touch, a small gesture that embodies a much needed turn to Humanism.

Maurice Sherif’s photographs capture the massive and monumental, yet piecemeal and prosaic, nature of the border wall. Sherif spent three years photographing the wall from California to Texas and brings the structure as a whole into public view, inviting scrutiny of its socio-cultural, environmental, and binational impacts. His photographs represent how the wall frames and indifferently militarizes historical and cultural sites, through its rusted metal and severe pretense. In the photograph University of Texas at Brownsville Rio Grande Valley Sector, the border wall intersects a white building generically labelled "ART MUSEUM" and provides a critical vantage point for pondering the intersection of culture and militarization. In their floor-toceiling print that emulates the grand scale of the wall, Scott Nicol and David Freeman photographed muddy footprints moving up the wall’s rusty bollard poles.

While its title, Section 0-21, mimics the military logic of the border security industrial complex, the footprints signify the humanity of border crossers.

In this exhibition, visitors cross a threshold, a checkpoint where their citizenship becomes suspect and under review. North the Checkpoint, (De Luna), an oil on canvas painting, depicts an interior checkpoint that draws attention to the camera and light arrays through which travelers must pass even though they are 75 miles north of the United States-Mexico border. The camera and light arrays teleport visitors into a virtual world where their images are reticulated onto crisscrossing security grids that compress experiences into a technologically accelerated space-time and transmutes personhood into algorithms and Non Structured Query Language searches. What kind of biometric data and photographs are these cameras capturing, and how are they being correlated with other information in the enormous data aggregators that enmesh citizen and noncitizen alike? The entrance to the exhibition reproduces these cameras and light arrays to provide visitors with an ephemeral sense of their empowerment over them. In this zone, can we challenge their all-seeing power and their infinitely flexible searchability?

The title Fencing In Democracy indexes how the border wall encloses democracy through suspending laws. In building the border wall, the U.S Department of Homeland Security waived thirty-seven laws. United States citizens had no legal standing to either challenge the construction of the wall or to contest its design and placement. In other words, the way in which the DHS organized the construction of the wall "fenced in" democracy’s creative power. This exhibition invites participants to ask: Would we have a wall if its proposed construction had occurred in a fully democratic setting with an ethos of democracy? Can border walls and international boundaries become eco-zones that produce green energy and sites of binational cooperation, as suggested by the architects Brown, Fratello, and Rael?

In the case of the actual border wall, democracy’s power was constrained; this exhibition allows participants and visitors to imagine alternatives and generate public dialogue about border militarization. While history offers many examples of building walls to restrict and control people, they crumble. But before they crumble, walls imprison, make legitimate human interaction across political borders illegitimate, and reduce democracy to tyranny. We can break down these barriers. De-fence Democracy.